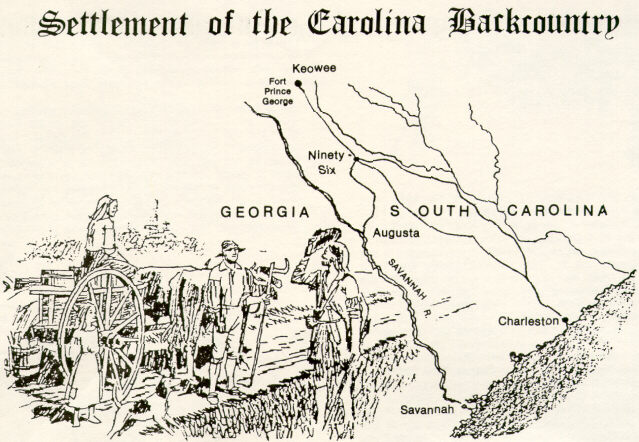

After the founding of Charles Towne (near the present city of Charleston, S.C.) late in the 17th Century, trade and commerce increased between coastal residents and Indians of the interior. The Cherokee Path was a primary trade route between Charles Towne and the inland Indian villages, but a number of the paths across South Carolina intersected at Ninety Six. The name "Ninety Six" came from an estimate that the site lay ninety six miles down the Cherokee Path from Keowee, a major Indian town in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Because of the intersecting paths and its convenience as a stop-over point, the area became a hub for trading many goods and services. Leather and pelts were the principal interest of white traders and were purchased from Indians and white hunters and trappers in exchange for guns, powder, rum and other supplies.

One of the most successful white traders was a businessman named Robert Gouedy who established a trading post in the area about 1751. Gouedy prospered here and expanded his commercial enterprises to include money-lending and farming. By the time he died in 1775, Gouedy owned over 1500 acres in the area, and almost 500 people owed him money.

The base of support offered by Gouedy's enterprises and the stores of other tradesmen in the area along with reliable water and fertile bottomlands gave rise to increasing settlement here. At first the Ninety Six community was a scattering of homes for several miles around, but by the mid-1750's, blacksmith shops and flour mills had complemented existing development.

White settlement around Ninety Six was on the rise, but friction with the Indians also increased. For a decade, Indian attacks were common throughout South Carolina, and settlers sought refuge in frontier forts. Fort Ninety Six was an example and was built around Robert Gouedy's barn. During the Cherokee War, over 200 Cherokees unsuccessfully attacked this fort in March, 1760. Finally, a treaty was signed with the Indians in 1761. According to the treaty, no Indian could travel below Keowee without permission, and the Indian's hunting privileges were also largely surrendered.

A resurgence in settlement in the Ninety Six area followed peace with the Cherokees, and as population increased, demands for schools, churches, good roads and law enforcement arose. With no police, outlaws preyed on local residents. Vigilante groups formed to provide protection. But the justice of these vigilantes was often severe, and the colonial government finally provided the backcountry with law enforcement authority in 1769. This took the form of courthouses and jails to be built in each of seven judicial districts. The law authorizing these structures in the Ninety Six District specified that the buildings be "within one mile" of Fort Ninety Six. They actually were finished in 1772 about one-half mile north of Fort Ninety Six and Gouedy Trading Post. Robert Gouedy was able to enjoy the benefits of law enforcement authority without his clientele being intimidated by having a sheriff, jail and courthouse directly across the street from the Gouedy Trading Post.

The courthouse and jail provided a focus for more development, and the village of Ninety Six began to evolve. On the eve of the American Revolution, Ninety Six Village contained at least a dozen buildings (courthouse, jail, homes, blacksmith shop) and was the new center of activity in the area.