Chapter 1

Organic Evolution And The Mental Continuity Doctrine:

Mental Darwinism Proposed And Elaborated (1859-1916).

Paul F. Ballantyne

Understanding the history of how and why qualitative differences were originally excised from early 20th century ability testing is the first step toward readmitting them in a truly transformative approach to mental assessment. In this chapter various 19th century foundations of the early 20th century continuity view of mind are outlined. This methodological approach to elaborating the relationship between animal and human mentality is shown to have a specific origin in the unwarrantably additive approach of both Darwin (1859; 1872) and Romanes (1882, 1884, 1888) to mental and cultural evolution (Tolman, 1987a). This shortcoming is contrasted with Darwin's (1859; 1871) "continuity and discontinuity" view of organic evolution which can only be described as transformative rather than merely additive or interactionist.

Chapter Overview

In section one, the views of Darwin (1859, 1871) on organic evolution (a.k.a. organic Darwinism) are shown to possess both continuity and discontinuity arguments, especially with regard to human descent. The subsequent early 20th century anthropological debate between proponents of the so-called "jaw first" doctrine (which logically follows from Darwin's approach to organic evolution) and the more influential "brain primacy theory" of hominid descent (which does not), demonstrates that even Darwin's carefully argued presentation of organic evolution was not sufficient to consolidate wider disciplinary support. On the contrary, the politically charged nature of all such debates is exemplified in the disciplinary marginalization of two important jaw first theorists (E. Dubois and R. Dart) who were vindicated by the evidence only in the mid-1950s. It is noted that, in our own discipline, a similar period of protracted debate (with regard to the relative mental abilities of species) has yet to be officially resolved.

In section two, Darwin's (1871, 1872) views on mental evolution (a.k.a. mental Darwinism), and those of Romanes (1882, 1884, 1888), are shown to contain mere continuity arguments. In fact it was Romanes (1888) who first pointed out that this methodological position was the logical outgrowth of Darwin's approach to mind. In this case, Darwin's own rather unDarwinian views on mental evolution have been accepted widely. Indeed, an implied continuity view of mind has been the primary reason behind the failure of successive "mental ladder" approaches to the empirical assessment of animal and human intelligence.

Section One:

Organic Evolution And Human Descent (Organic Darwinism)

Various theories regarding the origin of geological formations, plant life, and animate organisms were part of the early-to-mid-19th century intellectual ferment in Europe. In particular, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1809), sought to systematize the views of his own mentor (Buffon) into the doctrine of inheritance of acquired characteristics. Surprisingly, he openly applied this doctrine both to animals and also to the acquisition of upright posture, symbol manipulation, and language by our human progenitors (see Lamarck, 1809, In McCown & Kennedy, 1972). In doing so, he was making a clear break with the 18th century natural theology tradition that viewed all fossils as evidence of the biblical Diluvian flood (e.g., J. Scheuchzer).

Other more conservative forces, however, were also at work in the early years of the nineteenth century and these prevented Lamarck's position from becoming popular. George Cuvier (1796-1832) for example (while wrestling with the problem of how it could be that extinct animals could be reconstructed from fossil deposits) suggested that a series of floods had wiped out these old creations and cleared the way for new creations. This theory which Cuvier first described in 1812 (and elaborated in 1825), was called Catastrophism. Human kind was the product of recent history; a creature separated from the rest of the animal world by a great anatomical gulf and by a series of prehistoric catastrophes that limited the number of currently existing animal species. It was Cuvier's pronouncement (that: "L'homme fossile n'existe pas" -human fossils do not exist) which formed the basis for the widespread denial of the antiquity of numerous stone tools and occasional hominid finds prior to 1863 (see Wendt, 1971).

Darwin on Organic Evolution

Darwin's mid-19th century views on the organic evolution of species were intended as an empirically supported middle ground between the theologically based "argument for design" (which argued that current species are qualitatively separate and immutable), on the one hand, and the newer geologically based catastrophism (which argued that geological and biological features arose as a result of a few sudden and global cataclysms on the earth's surface). One of the main reasons Darwin eventually succeeded in gaining the approval of the biological community (for his mechanism of evolution) was that, in contradiction to the widely speculative Lamarck, he provided a selective and careful Baconian style elaboration of available (but non-contentious) empirical evidence.

Darwin's Origin of Species (1859) put forward the theory of natural selection to explain the occurrence of species differentiation under the long and relatively continuous effects of: (1) climate; (2) population isolation; (3) predation by other animals; and (4) sexual selection. Thus both passive adaptation and active adjustments of the organism were incorporated into his analysis. In his views on the gradual nature of organic evolution, Darwin was profoundly influenced by Charles Lyell's "uniformitarianism" views on gradual geological change across immense periods of time (first put forward in detail between 1830-33). Chapter VI of Darwin's 1859 book argues, for instance, that in the organic evolution of more complex species from simpler species, "Natura non facit saltum" -nature does not move by leaps, but through continuous gradation:

"Why should not Nature take a sudden leap from structure to structure? On the theory of natural selection, we can clearly understand why she should not; for natural selection acts only by taking advantage of slight successive variations; she can never take a great and sudden leap, but must advance by short and sure, though slow steps" (Darwin, 1859/1936, p. 144).[1]

Belief in the abrupt appearance of species, he argues, is largely due to the great gaps in the known geological record, which tend to hide the presence of transitional forms. Darwin had great faith that these gaps would eventually be filled in by persistent geological investigation. The discovery of various specimens of archaeopteryx (a transitional form between reptile and bird) between 1860-1877 indicated that Darwin was on the right track in this regard (see Ostrom, 1984).[2]

The above continuity aspect of Darwin's view of organic evolution has often been emphasized in the psychological textbooks (where it is implicitly argued that human beings are part of an unbroken chain of beings which differ in degree but not in kind). It should be recalled, however, that a large part of the original motivation for writing Darwin's 1859 book was to portray the exact nature of organic species differentiation in contradiction to those who claimed that species differences are immutable and timeless creations.

In his opening chapters, for instance, Darwin emphasizes that even though it is very difficult to distinguish two different species of flora from mere variations of the same species, it can be done. He draws attention to the long practiced technique of cross-pollination of rose varieties as an example. Similarly, he argues, the inability to cross-breed different mammalian species and the sterility of the progeny of those which can be cross-bred are also indications of their fundamental difference in kind.

On the basis of this empirical evidence, Darwin argued the more theoretical point that "specific characters" of a given species are more variable than "generic characters" that are common to groups of species (pp. 114-118). For example, the secondary sexual characteristics of male birds (e.g., colorful plumage) vary considerably between species, but these organs are generally displayed in the same parts of the body. This observational regularity suggested to Darwin that different bird species are descendants of a common progenitor, "from whom they have inherited much in common" (p. 117).

The important methodological consideration here is that the Darwinian position on organic evolution recognized, and incorporated, both continuous and discontinuous arguments. That is, Darwin recognized what is now called an objective contradiction in species differentiation: continuous changes in ancestral organisms eventually produce a change in anatomical/physiological kind. This gradual process of change in degree eventually produces a change in kind. Darwin's gradualism, therefore, should be understood within its historical (or disciplinary) context and should not be confused with an argument for pure organic continuity between species.

Awareness of the Audience

Darwin was aware that many of his colleagues would have great difficulty accepting his continuity/discontinuity hypothesis on the basis of the contemporary geological evidence:

"We see this in the fact that the most eminent palaeontologists, namely, Cuvier, Agassiz, Barrande, Pictet...and all our greatest geologists, as Lyell, Murchison, Sedgwick...have unanimously, often vehemently, maintained the immutability of species.... Those who believe that the geological record is in any degree perfect, will undoubtedly at once reject the theory [of natural selection]. For my part,...I look at the geological record as a history of the world imperfectly kept, and written in changing dialect; ....only here and there a short chapter has been preserved; and of each page, only here and there a few lines. Each word of the slowly-changing language, more or less different in the successive chapters, may represent the forms of life, which are entombed in our consecutive formations, and which falsely appear to have been abruptly introduced" (Darwin, 1859/1936, p. 255; emphasis added).

This disciplinary resistance was especially accute with respect to the contemporaneous interpretation of fossil hominid finds. In particular, Charles Lyell (1797-1875), despite his visits to many of the European prehistoric sites between 1830-1850, was particularly reluctant to apply his own gradualist view of geological change to human origins. This reticence condemned many of the pioneers in the study of human prehistory (e.g., P. Schmerling, and J. McEnery) to a long period of travail without official recognition.

For instance, only after reading Darwin's 1859 work did Lyell convert to the natural selectionist view with respect to the antiquity of human organic evolution. He quickly revisited many of the European prehistoric sites (including Schmerling's site near Liege) and published a book on the subject (see Lyell, 1863 In McCown & Kennedy, 1972). The young Thomas Huxley was also quick to publish essays on the known fossil remains of man in the same year as Lyell. His anatomical studies had led him to the conclusion that the structural differences which separate man from gorilla and chimpanzee are not as great as those which separate the gorilla from lower apes (see Huxley, 1863 In McCown & Kennedy, 1972). Both men also urged a highly reticent Darwin to address the topic of human organic descent more directly. Another decade would pass, however, before Darwin openly extended the hypothesis of natural/sexual selection to the organic genesis of human beings (1871).

Darwin was neither overly bold with his theorizing nor pedantic with facts. His great talent lay in the ability to look at past competing positions and select out that which must be retained from each in a new causal theory. This was most evident in his ability to both discover the general mechanism of organic evolution (i.e., natural selection) and to apply it to specific cases (e.g., the jaw first model of human descent). Ironically, while the particulars of his careful statements regarding human organic evolution (1871) were not accepted for some time, Darwin's lesser forays into the mental evolutionary realm (1872) were adopted both readily and widely. This contradiction within Darwin's work and the related history of its disciplinary treatment in the social sciences will be used to argue that psychology needs to move beyond the mental Darwinism contained in standard treatments of mental evolution.

Darwin on Human Descent

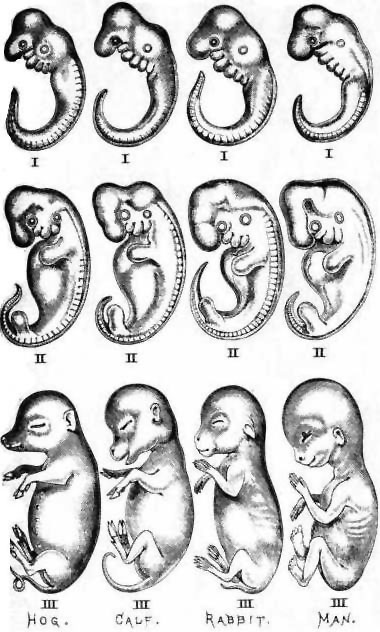

Initially, Darwin (1859) was prepared only to discuss the far distant ancestors of human beings. His own views on organic evolution, however, were finally extended to human kind in Descent of Man (1871). Once again, with regard to the physiological and anatomical aspects of descent, the continuous/ discontinuous argument was handled with consummate skill. On the continuity side, Darwin points out that the human embryo at two months is similar in structure to the embryo of other mammals (such as a dog). Similarly, the convolutions on the brain of the human fetus at seven months are similar to those of an adult baboon. Both of these facts, he argued, indicate remote but common mammalian ancestry (see fig 2).

Figure 2 Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. The organic development of the human embryo mirrors that of other mammalian species as listed in the figure (After Haeckel, photo from Romanes, 1901). Romanes (1882,1884, 1888) would carry this fundamental "biogenic law" into the realm of comparative mental evolution.

On the discontinuity side, man has unique bodily structures, such as an opposable thumb and bipedal gait, which were likely of paramount importance in the gradual evolution of our species:

"Man could not have attained his present dominant position in the world without the use of his hands, which are so admirably adapted to act in obedience to his will....But the hands and arms could hardly have become perfect enough to have manufactured weapons, or to have hurled stones and spears with a true aim, as long as they were habitually used for locomotion and for supporting the whole weight of the body, or, as before remarked, so long as they were especially fitted for climbing trees" (Darwin, 1871/1936, p. 434).

"As the progenitors of man became more and more erect, with their hands and arms more and more modified for prehension and other purposes, with their feet and legs at the same time transformed for firm support..., endless other changes of structure would have become necessary. The pelvis would have to be broadened, the spine peculiarly curved, and the head fixed in an altered position.... No doubt these means of change often co-operate... Hence the individuals which performed them best, would tend to survive in greater numbers...." (Darwin, 1871/1936, p. 435; emphasis added).

The cranial capacity of modern humans was noted by Darwin as one of these "other changes of structure," but he was also quick to point out that the so-called Neanderthal skull (discovered in 1856) is also "well developed and capacious" (p. 437). As the following quotation shows, Darwin's (1871) theory regarding the means by which the modern human brain developed has been aptly described as a face-first or jaw first model (see Bowler, 1984; G. Richards, 1987b; Lewin, 1993). Darwin continues:

"The free use of the arms and hands, partly the cause and partly the result of man's erect position, appears to have led in an indirect manner to other modifications of structure. The early male forefathers of man were...probably furnished with great canine teeth; but as they gradually acquired the habit of using stones, clubs, or other weapons, ...they would use their jaws and teeth less and less. In this case, the jaws, together with the teeth, would become reduced in size.... Therefore, as the jaws and teeth in man's progenitors gradually become reduced in size, the adult skull would have come to resemble more and more that of existing man.... As the various mental faculties gradually developed themselves the brain would almost certainly become larger. No one, I presume, doubts that the larger proportion which the size of man's brain bears to his body...is connected with his higher mental powers..." (Darwin, 1871/1936, pp. 435-436; emphasis added).

Darwin's legs first and jaw first model of of human descent is a fine example of his articulate and careful recognition of the inherent contradictions of the organic evolutionary process. According to his theory, it was the descent from the trees (creating selective pressure for upright posture) which indirectly brought about the increase in brain size through the freeing of the hands for the use of tools. Under such selective pressures, the hominid cranial bones, freed from the limiting effects of a constricting musculature (by the refining of the jaw) allowed an accompanying expansion of the brain size over a long period of time.

At the time, however, the Darwinian hypothesis regarding hominid evolution (a.k.a. the ape-man hypothesis) was just one of the extant theories. The early 19th-century phrenological and later craniometric traditions, with their dubious fixation on the shape and size of the head as a direct measure of intelligence, racial purity, occupational potential, and even societal status (see Gould, 1981) continued to exert a considerable bias upon the interpretation and acceptance of new fossil finds. This initially naive (cranio-centric) bias was, by the first part of the 20th century, formalized into a rather explicit brain first model of organic human evolution. Under such adverse disciplinary conditions, it would take evolutionary biologists and anthropologists over 100 years of protracted debate regarding the proper interpretation of successively uncovered fossil evidence before the accumulated fossil record would indeed provide a clear scenario of organic hominid evolution (in favor of Darwin).

The fact that a very similar pattern of extended acrimonious debate regarding the relative mental abilities among animals has played itself out in the field of comparative psychology, indicates that knowing a bit more about the so-called brain primacy debate might be useful before moving into discussion of the history of views on mental evolution proper.

Rise and Fall of Brain Primacy Theory

It is instructive to note that Darwin (1871) did not subscribe to what would later be called the brain primacy theory of human organic evolution.[3] This hegemonic and pernicious theory postulated that it was the development of a large brain in our hominid ancestors (with its accompanying growth in intelligence) which brought about the loss of apelike physical characteristics (including quadrupedal gait) thereby producing the human species. This theory exerted a considerable influence upon early to mid-20th century anthropology through the work of A. Woodword, W. Sollas, G. E. Smith, and A. Keith (see Gould, 1980a; Blinderman, 1986).

Part of the impetus, however, came neither from craniometry, nor from Anglo-Saxon arrogance, but from Ernst Haeckel's (1868) logical reconstruction of what a missing link between man and ape might look like:

"The form of their skull was probably very long, with slanting teeth; their hair woolly; the color of their skin dark; ... The hair covering...was probably thicker...; their arms comparatively longer and stronger; their legs, on the other hand, knock-kneed, shorter and thinner, with entirely under-developed calves; their walk but half-erect" (Haeckel, 1868, In McCown & Kennedy, 1972, p. 143; emphasis added).

This logical reconstruction was then reified in a painting by one of Haeckel's main rivals (see fig 3).

Figure 3 Haeckel's Pithecanthropus alalus (speechless ape-man) as depicted in 1894 by the painter Gabriel Max. This painting was commissioned by Haeckel's rival Rudolf Virchow (who was openly opposed to the application of the theory of organic descent to human kind). Instead of having the desired effect of making sport of Haeckel (who, in 1874, had been theoretically audacious enough to include pithecanthropus in a hypothetical evolutionary tree), the painting served instead to reify Haeckel's unsubstantiated postulation. This reified image, negatively influenced at least two decades of hominid specimen interpretation. It was later hung in the Haeckel Museum in Jena (photo from Wendt, 1971).

At least one of the above suggestions (i.e., that the legs of our immediate ancestor would be underdeveloped), was potentially dealt a severe blow when the Java man specimen (discovered by Eugene Dubois in 1891) was found to possess a well developed thighbone consistent with upright gait. The specimen was excluded as a possible hominid ancestor by the anthropological establishment, however, partly because it possessed such a small braincase. The powerfully placed German anatomist Rudolf Virchow, for instance, suggested that the remains were from a form of giant gibbon. This aspect of the rejection of Dubois's fossil find was in keeping with an implied brain first model of human evolution.

Dubois's reconstructive methods were also called into question at successive conferences during the year 1895. The skull cap and thigh bone had been found 50 feet apart and (in correspondence to the Haeckelian postulation of a stooped progenitor), critics suggested there was no necessary relationship between these bones. Dubois became so despondent over these narrow-minded reviews from the anthropological establishment, that he interred the bones under the floorboards of his house and permanently withdrew from the anthropological community.[4]

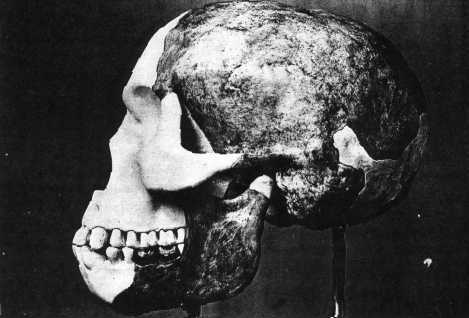

In 1912, the so-called discovery of the Piltdown man (with a skull capacity of a man but with an apelike jaw) in an East Sussex gravel deposit, seemed to confirm the disciplinary legitimacy of the brain primacy theory. This "Piltdown fraud" helped stall the advance of human evolutionary studies for more than a quarter-century -mostly because it so closely conformed to the apriori biases about what a primitive human skull should look like (see Weiner, 1955; F. Spencer, 1990; Tobias, 1994). As a consequence of such bias, there was little professional incentive to carefully scrutinize the evidence of the Piltdown find to the extent that Dubois's evidence had been scrutinized (see fig 4).

Figure 4 Piltdown (or 'Dawn Man') Skull as reconstructed by John Woodworth in 1912. A later reconstruction by Arthur Keith extended the cranial capacity by a further 30-40 percent over this original model (photo from Blinderman, 1986).

Similarly, the anthropological community again reacted with derision when Raymond Dart, in 1925, announced that he had discovered the true missing link between humanity and ape (which he named Australopithecus). His specimen, like Dubois's, did not possess a modern-size braincase, and therefore, (under the prevailing logic) could not have any bearing upon the hominid line (see Dart & Craig, 1959; Blinderman, 1986). It was only in the face of numerous other finds of australopithecus by Robert Broom, the Leakeys, and others during the 1930-40s that the prevailing brain first doctrine was brought into serious doubt. These finds indicated that austalopithecines (while possessing an average brain case capacity of only 450cc), also walked upright and possessed human-like teeth.

Finally, between 1949 and 1954, the Piltdown find was critically reexamined and revealed (by J. Weiner, W. Clark, and K. Oakley) as a clever composite of the jaw of an orangutan and the skull of a human (see Weiner, 1955). Joseph Weiner (1955), the instigator of this reanalysis, had been a student of Raymond Dart. The exposure of the piltdown fraud, however, was a vindication of not only Dart, but also of Dubois, Broom, and many other progressive but underecognized anthropological contributors (including A. Marston, H. Morris).

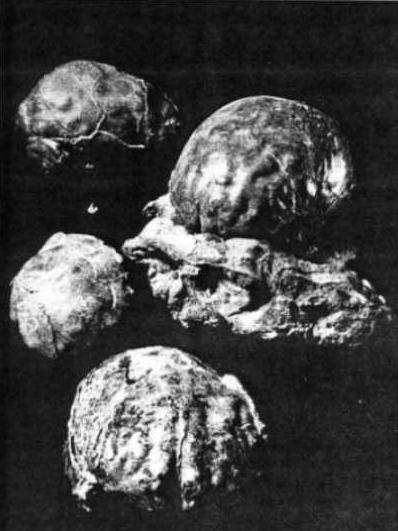

Subsequent evidence using both natural and artificial endocasts of hominid craniums, has continued to provide confirmation of the Darwinian hypothesis that both the hand and bipedal gait developed first with the brain getting larger only as the result of the adaptive advantages that these other structural changes allowed. In this regard, Dean Falk's (1992) critique of Ralph Holloway's idiosyncratic (and repeated) overstatements regarding the human-like characteristics of australopithecine brain sulci, can be viewed as the snuffing out of the last smoldering embers of the brain primacy theory (see fig 5).

Figure 5 Natural endocasts of Hominid brain case. Hardened limestone, and sedimentary deposits from ancient lake beds, occasionally mineralize hominid skulls (thereby preserving the rough record of the changing size, shape, and cranial bloodflow patterns). The cumulative record produced by these endocasts indicates a relative three-fold expansion of brain capacity between Australopithecus and Homo sapiens. This increase was also reflected in noticeable changes in the relative size of particular cortical regions including: (1) Frontal cortical expansion, (2) increase in association areas of various lobes (including Broca's area); and (3) more pronounced hemispheric lateralization. Scientists from various fields of knowledge are currently struggling to explain the causal relations involved in such organic evolutionary changes. It has been argued that not only physiological blood flow changes, but also increased social selection, and development of culture (society) is involved (photo from Falk, 1992).

The serious entertainment of the jaw-first model, and what it meant for modern anthropology, took place during a wider period in evolutionary biology called the modern biological synthesis (which lead up to the discovery of DNA). As Ernst Mayr points out in his One Long Argument: Charles Darwin and the Genesis of Modern Evolutionary Thought (1991), what happened in this modern synthesis was a "communal act" of theoretical house cleaning:

"What occurred during the period from 1936 to 1950, when the synthesis took place, was not a scientific revolution; rather it was a unification of a previously badly split field. The evolutionary synthesis is important because it has taught us how such a unification may take place: not so much by any revolutionary new concepts as by a process of house cleaning, by the final rejection of various erroneous theories and beliefs that had been responsible for the previous dissension. Among the constructive achievements...was the finding of a common language...and a clarification of many aspects of evolution and its underlying concepts" (Mayr, p. 135; emphasis added).

Similarly, the recent recognition of the possibility of sudden "transformative leaps" in brainsize growth of hominids (e.g., S. J. Gould's punctuated equilibria) is not intended to negate the existing fossil evidence for intervening periods of gradual and continuous growth. Instead, it is intended as a means to resolve past debates regarding the transition between such relatively stable forms and to make empirical suggestions as to what to look for in the ongoing drawing out of the actual pattern of brain-growth. At the very least, the succeeding generations of evolutionary biologists will now be better trained in the sorts of conceptual and empirical tools necessary to carry out such an investigation.

What Gould (1980b) has done with Goldschmidt's views of organic evolution, I wish to do with both emergent mental evolutionary views (of G. H. Lewes, 1877, 1879; C.L. Morgan, 1894/1904, 1923/31), and cultural-historical views (of Vygotsky & Luria, 1930). That is, outline a transformative mental evolutionary account and apply it to the area of mental testing.

Tripartite Scientific Paradox and Its Solution

The rise and fall of the brain primacy theory serves as a reminder that in all scientific debate there are often reasons, external to the currently available facts, which may sway an entire era of scientists toward one or the other vacuous endeavor or theory. Indeed, knowing where to look, what to look for, and how to understand new evidence depends on having some preliminary theory (or hypothesis) which orients you to evidence, methods, or implications that have not been recognized, investigated, or accepted by contemporary researchers. The consoling part of this apparent tripartite paradox (between fact, theory, and method) is that, given enough time, the practical consequences of holding one theoretical view rather than another are played out and tend to become evident to subsequent generations of scientists.[5]

The tricky part, then, is recognizing how to avoid being caught up in the present idols of the Cave, Marketplace, and Theater. Fortunately, three ways of avoiding these idols of scientific discourse are available: (1) obtaining an historical/developmental analysis of your area of interest by taking a hard look at the practical consequences of past research or theoretical practices (which might lead to a responsible choice among already existing alternatives); (2) creating a makeshift eclectic combination of contemporaneous approaches (all coexisting in a self-contradictory though practical mass); and (3) the creation of a novel approach through reformation of previous beliefs.

Favoring the first and third options above, I will eventually argue that the emergent evolutionary (a.k.a. transformative) approach to mental evolution is the best (though little recognized) means to avoid one of the more pernicious and disruptive manifestations of the contemporary "idols" at work in general psychology (i.e., the continuity view of mental evolution). This continuity view, however, is currently as entrenched in psychology as the brain primacy theory was at the turn of the last century. Section two of this chapter will demonstrate from whence it came.

Section Two:

The Mental Continuity of Species Doctrine (Mental Darwinism)

This section outlines the views of Darwin and Romanes on mental evolution. It is shown how the implicit emphasis of Darwin (1871; 1872) on the mental continuity of species was made into an explicit doctrine by Romanes and then applied to the full animal series including humans for the first time. Engaging the details of their argumentation is instructive because it shows how very little our implicit position on mental evolution has changed in the succeeding century. This, I propose, is not a strength but a weakness in the methodology of contemporary general psychology.

Darwin on the Continuity of Mental Evolution

As pointed out above, Darwin's argument for organic evolution recognized both continuous and discontinuous aspects in the organic evolutionary origin of species (i.e., adaptive divergence from ancestral varieties eventually produced distinct species which could not interbreed). It is highly ironic, therefore, that Darwin was decidedly unDarwinian, when considering the evolution of mind. In Descent of Man (1871) Darwin most lucid moment on the point of human mentality seems to suggests both continuity and discontinuity. That is, he suggests that the intellect of "a savage who uses hardly any abstract terms, and a Newton or Shakespeare....are connected by the finest gradations.... [and that] it is possible that they might [have at some distant time passed] into each other" (Darwin, 1871/36, pp. 445-446). However, by the end of three fateful chapters on mentality (about to be described), Darwin had fallen back considerably from this progressive position.

First of all, his two chapters on the "Comparison of the Mental Powers of Man and the Lower Animals" were specifically tailored to "show that there is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties" (p. 446). After presenting largely anecdotal evidence, he concludes that the "difference in mind between man and the higher animals great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind" (p. 494).[6] In particular, Darwin emphasized the impossibility of pinpointing any clearly impenetrable mental discontinuities between man and animal:

"If it could be proved that certain high mental powers, such as the formation of general concepts, self-consciousness, & c., were absolutely peculiar to man, which seems extremely doubtful, it is not improbable that these qualities are merely the incidental results of....the continued use of...language" (Darwin, 1871, p. 495).

His immediate goal, of course, was not to denigrate human mentality but to argue that even human faculties (i.e., intellectual and moral abilities) must have evolved gradually from lesser forms. They were not divine, occasional, gifts of a deity, but a product of the long and continuous workings of natural selection. In order to support this position, Darwin attacks the various past arguments for mental discontinuity:

"I formerly made a collection...of such aphorisms, but they are almost worthless.... It has been asserted that man alone is capable of progressive improvement; that he alone makes use of tools or fire, domesticates other animals, or possesses property; that no animal has the power of abstraction, of forming general concepts, is self-conscious and comprehends itself; that no animal employs language; that man alone has a sense of beauty, is liable to caprice, has the feeling of gratitude, mystery, &c.; believes in God, or is endowed with a conscience" (Darwin, 1871/36, p. 451; emphasis added).

It was in this negative and rather exclusionary manner that the continuity of mental evolution doctrine was first put forward. How very different these two chapters on mental evolution are from the positive (and largely inclusionary) approach Darwin takes to organic evolution elsewhere in The Descent. This difference in style is both carried over and intentionally accentuated by Darwin in the next chapter "On the Development of the Intellectual and Moral Faculties during Primeval and Civilized Times." Here, Darwin provides a hopeful opening by acceding to Russell Wallace's (1868) rather progressive position on the relationship between organic and cultural evolution, but he immediately falls back on Lamarck's inheritance of acquired characteristics with respect to mental evolution.

On the probable organic/bodily evolution of human beings, Darwin suggests, (along with Wallace) that after "man" invented weapons, and "tools, ...to procure food and defend himself" he was "little liable to bodily modifications through natural selection" (1871, p. 496). In other words, Darwin openly recognized that cultural evolution not only overcomes the limits of bodily adjustment (both passive and active) but also created new possibilities of existence and adjustment beyond natural or sexual selection (i.e., civilized manipulation of the environment): "When he migrates into a colder climate he uses clothes, builds sheds, and makes fires; and by the aid of fire cooks food otherwise indigestible....Even at a remote period he practiced some division of labor" (1871, p. 496).

When discussing mental evolution, however, Darwin becomes quite Lamarckian. He not only recognized this contrast in his own position, but laid particular stress upon it: "The case, however, is widely different,...in relation to the intellectual and moral faculties of man. These faculties are variable; and we have every reason to believe that the variations tend to be inherited" (p. 496). Despite his original intent (i.e., to trace the gradual evolutionary origins of human mental faculties), the end result of Darwin's analysis was indeed to denigrate human mentality by deferring to Spencer's (1855) speculative appeal to inheritance of acquired characteristics as a mechanism for mental progress. At best, Darwin occasionally portrayed the existing differences in human mentality as the mere additions of culture to an essentially biological organism. Under such a dictum, it is difficult to see how one form might pass into another form because the very style of analysis tends to totally negate any difference.

Darwin's (1872) continuity view of emotions

Darwin's original intent was to include a chapter on emotion in his Descent, but this information became too bulky and was published as a separate book the following year. In Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) the ostenstive reason for looking at animal examples was to show the "origin, of the various movements of expression" (1872, p. 17). The underlying goal, however, was to provide further empirical evidence for his previously anecdotal supported argument for quantitative rather than qualitative differences in mental evolution.

In this book, much of Darwin's comparative anthropological evidence was collected by way of a survey sent out to pastors, missionaries, and government officials in all corners of the British Colonial Empire. The survey contained questions such as: (1) Is astonishment expressed by the eyes and mouth being opened wide, and by the eyebrows being raised?; (2) When a man is indignant or defiant does he frown, hold his body and head erect, square his shoulders and clench his fists?; and (3) Do children when sulky, pout or greatly protrude the lips?, etc.

Darwin also enlisted the aid of accomplished actors to portray the particular emotions in a supporting role to his survey evidence. Photographs of these portrayals were then compared with photos of children to demonstrate the presence of such "emotional expressions" from a very early age. In addition to this anthropological and ontogenetic evidence, Darwin included photos of Duchenne's research involving the galvanic stimulation of an elderly man's face (see fig 6). This latter physiological evidence (which isolates the muscles at work in each of the various human emotions) was then used in a phylogenetic comparison with similar animal displays. Today of course, a single anecdote using a bizarre technique is not considered evidence. However, viewed within the context of the times, Darwin can be applauded for bringing all of the available empirical evidence to bare on the question of emotional types and origins.

Figure 6 Simulation and stimulation of "emotional expressions." Left panel: An actor simulates the bodily expressions associated with the emotion of "disbelief." Right panel: The electrical stimulation of facial muscles of an old almshouse inmate who could not feel pain in his face. The French physiologist Duchenne had produced hundreds of artificial "expressions" in this manner (photo from Darwin, 1872).

The important theoretical point here is that, for Darwin, similar bodily expressions indicate the same state of mind in both in animals and humans. The raising of hair (in all mammals); the showing of the teeth; or the enlargement of the body (in many other animals), indicate the same aggressive state of mind. Clinical reports of congenitally blind children also served as apparent corroboration of this position:

"The inheritance of most of our expressive actions explains the fact that those born blind display them....We can thus also understand the fact that the young and the old of widely different races, both with man and animals, express the same state of mind by the same movements" (Darwin, 1872, p. 351).

Romanes on Mental Evolution

Ten years after Darwin, a more explicit continuity argument regarding mental evolution was put forward by George J. Romanes (1848-1894). This Canadian born evolutionary biologist took an Oxford degree in physiology (1873) and wrote three major books regarding the mental evolution of animals and man. The first of these, Animal Intelligence (1882) has been widely accepted as the first textbook of "comparative psychology." Some form of appeal to mental continuity, he argued, was necessary because "no other alternative" theoretical understandings yet existed. Subsequent works in the area chastised Romanes for overuse of anecdotal evidence but they readily accepted his initial methodological assumption of mental continuity (see Chapter 2).

In his Animal Intelligence, Romanes justified this comparative psychology by suggesting that if we may speak of the evolution of physiological processes, then surely we may speak of the evolution of mental processes as well (Lowry, 1971, p. 118). Darwin's influence, here was both personal and intellectual for Darwin had made available to Romanes his personal field notes, observations, and newspaper clippings regarding the mental activities of animals (see R. Richards, 1987). Romanes then combined Darwin's notes with his own thorough and critical search of available anecdotal evidence.

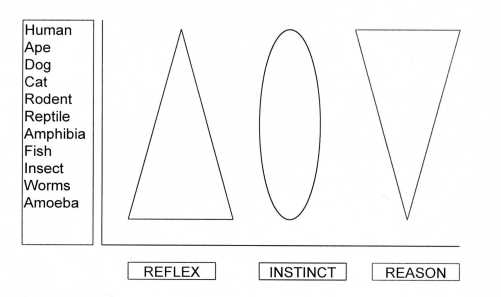

Upon this basis, he argued that "there must be a psychological, no less than a physiological, continuity extending throughout the length and breadth of the animal kingdom" (Romanes, 1882, p. 10). The core theoretical argument of this "continuity" view was that all animals contain at least some degree of Reflex, Instinct, and Reason. His method of exposition was to pass "the animal kingdom in review in order to give a trustworthy account of the grade of psychological development... presented by each group" (p. vi).

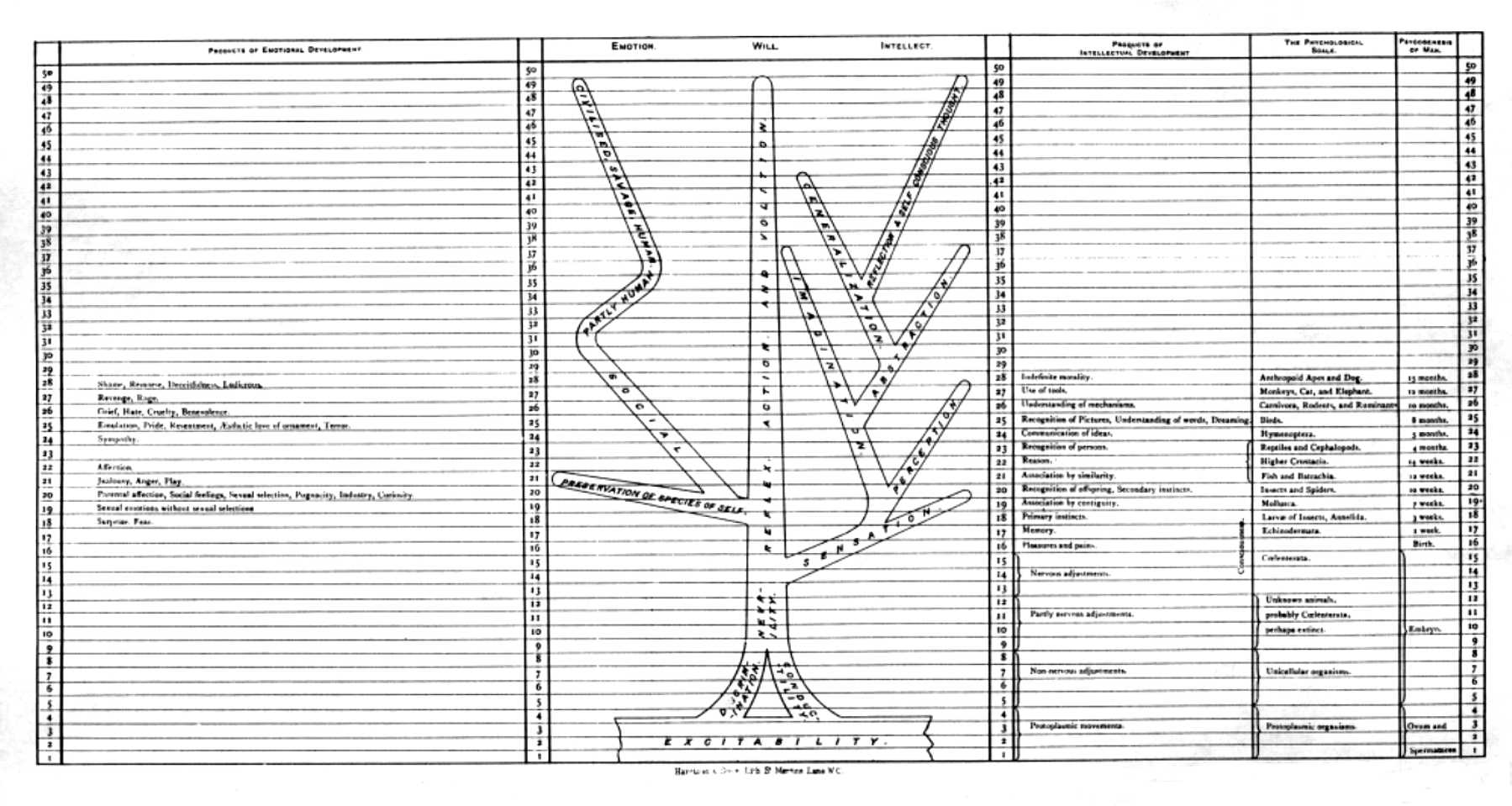

For Romanes, instinct was defined as "adaptive mental action (whether in animals or human beings),...without...knowledge of the relation between the means employed and the ends attained" (p. 16). Reason, on the other hand, was adaptive mental action which involves "knowledge of the relation between means and ends" (p. 16). His early view of mental evolution is shown in figure 7.

Figure 7 Depiction of the continuity view of mental evolution. Romanes claimed in Animal Intelligence (1882) that all animate creatures possess some degree of reflex, instinct, and reason. Although he never reified this early assumption in a diagram, a case can be made for doing so now because subsequent comparative psychology also adhered to this clearly mental Darwinist assumption. While Romanes (1888), explicitly demurred from this pure continuity view of mental evolution, advocating instead "qualitative differences" between species, the dye was already cast and the vast majority of subsequent comparative psychology advocated variations on the continuity theme (diagram after Tolman, 1987a).

In the chapters on ants, bees, and spiders Romanes (1882) presents numerous anecdotal examples of "intelligent adjustment" in insects. The "reasoning power" of ants, for instance, although shown by past experiments to be "almost nil," is suggested by Romanes to be "not quite nil."

"A nest was made near one of our tramways, and to get to the trees the ants had to cross the rails, over which the wagons were continually passing and repassing. Every time they came along a number of ants were crushed to death. They perseverated in crossing for some time, but at last set to work and tunneled underneath each rail. One day, when the wagons were not running, I stopped up the tunnels with stones; but although great numbers carrying leaves were thus cut off from the nest, they would not cross the rails, but set to work making fresh tunnels underneath them" (Romanes, 1882, p. 140).

It would be a mistake, however, to perpetuate the modern myth that Romanes was an "uncritical" anecdotalist. On the contrary, it is clear that he understood the limitations of both the anecdotal method and his own continuity position on mental evolution. For one thing, he sets out explicit criteria for the inclusion of only "reliable" anecdotal evidence in his book (pp. viii-ix). For him, this meant that a report must be corroborated by other similar reports.

In the same way, he also openly acknowledged the limitations of his own continuity view:

"Therefore, having full regard to the progressive weakening of the analogy from human to brute psychology as we recede through the animal kingdom downwards from man, still, as it is the only analogy available, I shall follow it throughout the animal series" (Romanes, 1882, p. 9; emphasis added).

It is clear that both his empirical method and his theoretical position on mental continuity were put forward by Romanes as state of the art arguments. He argued, for instance, that just as the "divine Mind" is known only through the imperfect analogy of the human mind, so to (in the absence of experimental evidence) must we use a similar "inverted anthropomorphism" to study the animal mind (p. 10). Likewise, as indicated by the previous quotation, Romanes believed this evolutionary continuity approach to be the "only" option available to a late-19th century scholar.

Romanes published two other distinctly related texts (1884, 1888) which further illustrate the details (and methodological tensions) of his early continuity view of mind. His Mental Evolution in Animals (1884) provided a diagram "of the probable development of Mind from its first beginnings in protoplasmic life up to its culmination in the brain of civilized man" (p. 63). On the basis of his observations of the various phyla, this diagram locates the first occurrence of sensation (in the coelenterate); of perception (in insect larvae); of imitation (in insects and spiders); of abstraction (in birds and rodents); of generalization (in anthropoid apes and dogs); and of conscious reflection (in man).

Figure 8 Full-sized lithographic diagram depicting mental evolution in animal and man (from Romanes, 1888). Both the central Darwinian "tree trunk" of this diagram and the more distinctly Romanes categorical columns (left and right) are telling indications of the assumptions underlying his later views on mental evolution. As Boakes (1984) has pointed out, while Romanes professed to maintain a Darwinian viewpoint, his argumentation and diagrams demonstrate his demur from the former pure continuity view. What appears on the central branches are not various orders and genera, but psychological terms. These are presented as falling into 50 levels of mentality and into a linear (temporal/stage) line, with which Darwin (and the pre-1882 Romanes) would not have agreed. However, while Boakes (like most comparative psychologists) treats this change as an inconsistent mistake, I will argue that it was a small but potentially progressive conceptual step by Romanes.

In the far left margin, of his diagram, (see fig 8), the first phylogenetic occurrences of various emotions are also depicted in a mental hierarchy: surprise and fear (in annelids); jealousy or anger (in fish); pride (in birds); grief and benevolence (in rodents); and shame (in anthropoid apes and dogs). To the modern reader, this diagram may seem to show that there is an evolutionary continuity and discontinuity being demonstrated. The point at which Romanes was tempted to "truncate" his original diagram (in the first of the two related works), however, is instructive because it indicates that his position (like Darwin's) postulates the presence of the same higher faculties in animals and in man.

"At first I intended...to truncate the...diagram at the level where mental evolution in animals ends -i.e., at the level marked 28- and to reserve the continuation of the stem and branches, as well as that of the parallel columns, for my ensuing work. But afterwards I thought it was better to supply the continuation of the stem and branches, in order to show the proportion...of the higher faculties as they occur in animals and the same faculties as they occur in man" (Romanes, 1884, p. 65; emphasis added).

Importantly, by the time Romanes published his related work Mental Evolution in Man (1888), some of the central aspects of his prior position were beginning to change. Most importantly, he now recognized "cogent" evidence that the (continuity) doctrine of descent alone does not account for the "mental constitution" of human beings (p. 390). The doctrine of cumulative "proportion" was now applicable to the "whole of organic nature, morphological and psychological, with the one exception of man" (p. 390). For Romanes, the "distinctively human qualities of ideation," (e.g., conscious reflection) formed the undeniable, ontologically cogent evidence of the "qualitative" difference between humans and brutes.

Having pointed out this descriptive difference, however, Romanes (1888) did not go so far as to explain the origins of this difference. The terms "quality and quantity" are used many times by Romanes but his comparative analysis remains de facto a method of quantitative proportion (i.e., analysis of degree and not kind). For instance, instead of suggesting that animal and human abilities form a nested structure of transformationally different abilities (i.e., as Darwin had done for organic evolution of hominids), Romanes suggests that the specifically human influences on mind go on in "parallel" with a more general organic and psychological continuity (p. 391). This had the effect of leaving unscathed the older associationist doctrine that specifically human abilities are simply superimposed upon or added to the abilities that already exist (to a greater or lesser degree) in animal psychology.

The following ontogenetic argument is the means by which Romanes put across this delicately equivocal point. We should note that it is virtually indistinguishable form the standard analysis still used in general psychology:

"For it is thus shown to be a matter of observable fact that, whatever may have been the origin or the history of human intelligence in the past, as it now exists...it proves itself to be no exception to the general law of evolution: it unquestionably does admit of gradual growth from a zero level, and without such a gradual growth we have no evidence of its becoming. Furthermore, so long as it is passing through the lower stages of this growth, the human mind ascends through a scale of faculties which are parallel with those that are eminently presented by...the psychological species of the animal kingdom -a general fact which tends most strongly to prove that, at all events up to the time when the distinctively human qualities of ideation are attained, no difference of kind is apparent between human and brute psychology" (Romanes, 1888, p. 391; emphasis added).

Despite its minor inconsistencies, and familiar methodological flavor, this equivocal position by Romanes also provided a transitional (rather than transformative) groundwork upon which later "interactionist" evolutionary positions could be built. One of the indications of the transitional status of Romanes' (1888) position is that the former (1884) diagram reappears in essentially unaltered form. In the far right margin, Romanes again provides the ages at which the various phylogenetic achievements of mental evolution in animals are attained by the individual human child. The "reasoning power of reptiles and cephalopods," for instance, is attained by the human infant at 4 months.

In other words, Romanes had simply extended Haeckel's so-called fundamental biogenetic law from the physiological to the psychological realm. That is, psychological ontogenesis (development of the individual human), recapitulates the psychological phylogenesis of the species. The "brute psychology" is still there but is simply overlaid with the one qualitative human novelty, "Ideation." In the Romanes (1888) account, ideation can be considered as a higher rung on an additive mental ladder.

Conclusion

The underlying additive structure of both mental Darwinism and the transitional recognition of qualitative differences (in Romanes, 1888) would become an ongoing concern for those seeking to empirically corroborate the existence of qualitatively graded "mental ladder" rather than a purely continuous "mental chain" (e.g., Candland, 1993). As shown in the next few chapters, however, many of the most influential figures in 20th century psychology viewed these concerns as lying outside the purview of an empirically rigorous science. Consequently, a de facto mental continuity doctrine did not end with the early views of Romanes but was, instead, adopted directly into both mainstream animal psychology and the American human ability testing tradition.

[1]All of the page numbers from Darwin (1859, 1871) correspond to the standard combined volume published in 1936.

[2]Discovery of archaeopteryx specimens, in turn, was followed by considerable debate over whether it possessed secondary feathers; whether it perched in trees; whether it was able to fly; and what its diet may have been.

[3] This is likely due to the fact that Darwin knew that the Neanderthal skull (found in 1856) possessed a braincase of 1600cc, which is larger than the average modern human skull (at 1500cc).

[4] The Java man bones were only re-exhumed in 1927.

[5] Francis Bacon in his appeal to nature as a new source for authority distinguished between idols of the Tribe (which have to do with the limitations of all human knowing -we never have absolute or static knowledge); idols of Cave (which have to do with the individual limitations, educational experience, and loyalties of given investigators); idols of the Marketplace (which have to do with the limitations of current language or terms used in scientific discourse); and idols of the Theater (which have to do with conceptual limitations set up by apriori systems of thought) (see Bacon in Burtt, 1939).

[6]This

has been the fundamental methodological assumption of much comparative psychology

and has been carried directly into general psychology.