Chapter 2

American

Animal Psychology and the Eugenics Movement:

Mental Darwinism institutionalized

(1900-1918).

Paul F. Ballantyne

The mere reference to both qualitative and quantitative differences in mental evolution made by George Romanes (1888) did not solve the problem of continuity and discontinuity. It did, however, raise another pressing question: What sort of empirical practices might be developed to expose or reflect these qualitative changes in mental evolution? The early debates on this question were accompanied by, and sometimes aimed against two forms of methodological excesses (i.e., anthropomorphism and psychophysical reductionism). Within both early American experimental psychology and evolutionary zoology, there was considerable debate regarding not only how to go about studying the animal mind but also whether there is a legitimate and distinctly psychological reason for doing so (see, Plotkin, 1979; Tolman, 1987b; Wyers, 1987b).

The echoes of these debates still reverberate in the opening chapters of contemporary comparative psychology textbooks. What is not often mentioned, however, is that these early debates took place within a wider societal context of at least one form of political-disciplinary excess: eugenics (Allen, 1986; 1997). Our continuing disciplinary inability to provide an unequivocal account of the uniquely psychological aspects of comparative mentality has made North American general psychology vulnerable to successive reductionist attacks (e.g., mind-stuff theory 1880-1890; eugenics 1900-1955; instrumental behaviorism 1913-1950, operant behaviorism 1938-1980; sociobiology 1969-2001).

In this chapter, the efforts of German physiological psychologist Oskar Pfungst to investigate the Clever Hans phenomena (1904-07) will be used as an exemplar of the early European style of coordinated research programs (i.e., combining observational, zoological, and laboratory analysis with sincere efforts at theoretical synthesis). This European synthetic approach contrasts strongly with John B. Watson's consistently analytic (and antievolutionary) approach to animal and human psychology. It also contrasts with the more evolutionary, yet logically contradictory, approach taken toward animal and human mentality by Robert Yerkes (who first flirted with eugenics and then embraced the mental testing movement as another means of promoting the discipline).

In my opinion, this very contrast between early European synthesis and American analysis, exemplifies the ongoing difference between sundry historically explanatory glimpses of mental evolution and the more widespread abstract generalization or the somewhat less frequent concrete descriptive used of comparative methods (see also Ballantyne, 1995).[7]

Section One:

Pfungst and the Blight of Lay-public Anthropomorphism

The first form of methodological excess, anthropomorphism, was present in numerous textbooks written by evolutionary naturalists for the European general public between 1859-1890. The U.S., translations of Binet's Psychic Life of Micro-organisms (1894/1910) and Forel's Ants and Some Other Insects (1904), combined with J. Lubbock's Ants, Bees and Wasps (1882) are just some of the later examples of this trend. As with Darwin and the earliest works of Romanes, these texts tended to interpret animal movements by direct analogy to human-like actions, memories, and intentions.

While anthropomorphism was not adopted by most serious comparative scientists after 1900, it did continue unabated in the European and North American lay public (largely as a means of entertainment at various "clever animal" shows). It was this grand theater, that provided one of the first well-publicized showcases for the application of the new German physiological psychology to investigate animal mentality.

The logic of anthropomorphism

Under the logic of the strict continuity view of mental evolution, it might be possible (under the right environmental circumstances) for a the occasional exceptional animal, which just happened to possess an unusually high endowment of latent reason, to perform mental acts such as reading, mathematical calculation, and music appreciation. Indeed Darwin, himself seemed to imply this point at times: "We have seen that the senses and intuitions, the various emotions and faculties such as love, memory, attention, curiosity, imitation, reason, & c., of which man boasts, may be found in an incipient, or even sometimes in a well-developed condition, in the lower animals" (Darwin, 1871/36, p. 495). For instance, he argued that it might be due to a lack of "exercise" that apes do not speak (for they seemed to have adequate anatomical organs to perform this function).

The Clever Hans Controversy

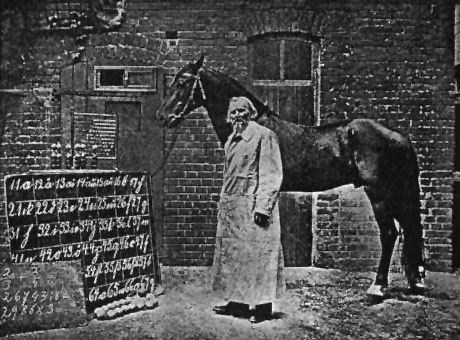

In 1904, it was an admixture of this new evolutionary viewpoint with older craniometry, that led Mr. von Osten (a retired grade school teacher) to sincerely believe he had developed a means to train and demonstrate human-like intelligence in especially bright horses. In fact, during the regular public courtyard demonstrations of the horse's abilities, von Osten, occasionally compared the skull of his previous horse (Hans I, which he considered to be exceptionally bright but which had died during training), with that of his current equine student "Clever Hans" (see Krall, 1912).[8]

In short, von Osten believed he had constructed a training regime that could potentially be used to draw out the hereditary latent intelligence in not only horses but also in rural schoolchildren. It was, he suggested, simply a matter of applying the "appropriate didactic methods" (Bringmann & Abresch, 1997, p. 78). While the exact details of von Osten's educational techniques have been lost to posterity, it is likely that their effectiveness (as evidenced by Hans' performance under experimental conditions) lies in the social relationship established between owner and horse and not in either hereditarian latent intelligence or in the mechanical stamping in of environmental cues (see fig 9).

Figure 9 Clever Hans and owner. Note the abacus (background), lettered chalkboard (foreground), and other apparatus (including weight estimation balls) used to demonstrate the purportedly well-developed mental abilities of this unusual stallion (Pfungst, 1911/1965; Katz, 1937). Von Osten had trained Hans to "answer questions" by tapping his right front hoof; and by either taking up objects in his mouth, or "pointing" to them with his muzzle. The details of this "Clever Hans affair" are important because neither the results nor the dynamics of such training can be accounted for solely on the basis of standard associationist psychological theories of learning (e.g., classical or operant conditioning, cognitive processes). Only by a truly "transformative" evolutionary approach to psychological investigation can the nature of Hans' cleverness be explained.

A public commission

Dismayed by mounting accusations of fraud from the press, von Osten (who had never charged the public a fee) appealed to the local school board for an investigation into both the veracity of his claims regarding Hans, and the viability of his training methods. A commission of inquiry was soon formed. It consisted of thirteen dignitaries including two teachers, two zoo directors, two military majors, a circus manager, a veterinarian, a count, a magician, a horse trainer, and two academics (one of which was Carl Stumpf director of the Psychological Institute at the University of Berlin). On the first day of the enquiry, various members were assigned to watch different parts of von Osten's body while he asked the horse questions regarding colored cloths, photographs of public figures, and the spelling of certain words. Hans, performed well and no visual or auditory signals were observed to be passing from handler to horse.

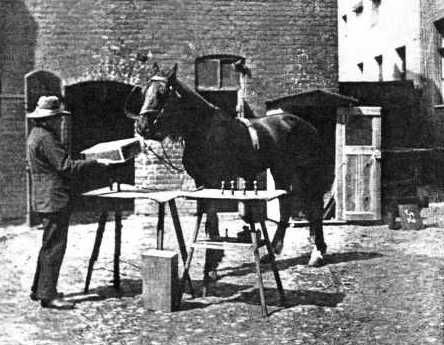

The next day, a set of more difficult tasks was demanded by the commission (see fig 10). But even when von Osten stood behind an assigned questioner, back to back, yet bending forward himself (thus decreasing the possibility of visual signs being passed), the horse again "answered questions" with very few errors. For instance, when six slates were suspended in a row along a rope, each with the name of a commission member written on it, Hans was able to indicate the correct slate by tapping out its position in the strung up line. With intentional deception now ruled out, the way was open for finding out just how the horse did it and Stumpf assigned this difficult task to one of his University of Berlin graduate students Oskar Pfungst.[9]

Figure 10 Hans is asked a mathematical question. The questioner (von Osten in this case) would raise the first wooden box from the right table revealing some pegs. Hans was then asked verbally to "add, multiply, or divide" this number by the second number of pegs indicated by raising a second wooden box. Note the open storage shed (upper right) where demonstrative equipment including lettered placards, chalk slates (for names), common-place objects, and photographs (of people or objects) where stored (photo from Krall, 1912).

The observational study

Between 1904 and 1907, Oskar Pfungst (1874-1932), used a combined approach of observational, experimental, and laboratory methods of controlled variation of conditions to establish a rough outline of the mental abilities (and limitations) of Clever Hans the performing horse (see Pfungst, 1911; Krall, 1912; Katz, 1937; Rosenthal, 1963; Fernald, 1984; Bringmann & Abresch, 1997).

Pfungst's first order of business was to confirm or deny the commission's findings. As the commission had found no visual signals, Pfungst's initial suspicion was that surreptitious nasal whispers might be involved in prompting the horse.

Observing Hans in the usual courtyard show setting, Pfungst noticed that shouts by spectators did not interfere with Hans's performance. The horse also exhibited very little ear movements during questioning. These observations cast considerable doubt on the nasal whisper hypothesis. Importantly though, Pfungst noted that Hans's performance dropped when the distance from the questioner increased, and also decreased considerably with the onset of darkness. Neither intentional movements nor nasal whispers on the part of the handlers (von Osten and C. G. Schillings) were noted so Pfungst concurred with the commission's findings regarding the lack of deception.

The experimental study

The experimental phase of research was aimed at establishing the breadth or limits of Hans's abilities to answer questions under systematically controlled conditions. It was carried out in the courtyard, but in the absence of an audience. A tent was also erected so that some of the experimental tests would not be confounded by movements in the surrounding tenant flats. One experimental test involved use of placards on which numbers were printed in large type. Two conditions were used, one in which the questioners knew the answers and one in which they did not (see fig 11).

Figure 11 Von Osten, Hans, and Pfungst. A placard is presented to Hans under the watchful eye of Oskar Pfungst a persistent, organized, and perspicacious investigator. Pfungst's integrative (rather than associationist) scientific methodology, which utilizes both analytic (i.e., observational, experimental), and synthetic (i.e., deductive comparative) research techniques, has only recently made a comeback in North American psychology as an alternative to the long-standing operationist and Popperian falsificationist methodologies (photo from Krall, 1912).

For the experimental condition, each placard was read by the questioner and then shown to the horse. In these "with knowledge" trials Hans readily tapped out the correct answer. For the control condition, placards were randomly shuffled face down and then, without seeing what was written on the other side, the questioner held one up for the horse. Hans' famous success rate decreased dramatically. Next, a similar procedure was use with a name written on slate tablets. Similar results were obtained. Pfungst had demonstrated that Hans could not read numbers or words. Ever cautious, however, Pfungst also designed another "without knowledge" procedure in order to test "non-reading" (i.e., auditory) addition skills. He simply whispered a given number into Hans's ear and von Osten did likewise into the other ear and Hans was to tap out the sum. Again, the same dismal results were obtained.[10]

These initial experimental tests indicated that, under normal uncontrolled conditions, the questioner was somehow providing Hans with information about which object to select or how many taps to make. The issue remained open, however, as to how this information was being passed from man to horse.

To test the ever-popular mental telepathy hypothesis, Pfungst devised a test where the questioner would know the answer in both of two sets of trial conditions, but where Hans could actually see the questioner in only one set of trials. In the second set of "control" trials, Has was prevented from seeing the questioner by a modified horse blinder. Later, this telepathy hypothesis was retested by having the questioner stand behind a wooden screen. On both occasions, however, Hans was unable to answer correctly under the control condition of visual impediment (see fig 12).

Figure 12 A modified horse blinder to test for telepathy. By augmenting a standard horse blinder with a dark cloth, it was hoped that all visual contact between Hans and the questioners would be abolished during the initial "control" condition trials. But Hans often reared or shook his head violently during these trials. Pfungst's recording secretary (Dr. E. von Hornbostel) was therefore forced to create an "undecided" category for those trials where Hans might have peaked. As Candland (1993) points out, despite this experimental difficulty, the chances of the percentages of correct answers obtained (i.e., experimenter seen = 89, experimenter not seen = 6, and undecided = 18) being due to chance are <.01.

Pfungst claims that he was first tipped-off to the visual signal hypothesis by an apparently hesitant, modified, half-step which Hans often exhibited just before ceasing his tapping (1911, pp. 47-48). In conjunction with the other evidence, Pfungst first deduced that Hans may be simply tapping until he saw a given signal to stop. Although Pfungst set up further experimental conditions designed to isolate the exact visual signal being picked up by Hans, the results were inconclusive without the aid of moving film. He did note that the typical questioner (some less than others) appeared to bend forward slightly from the waist after presenting a question in order to visually count the number of hoof taps and bent backward and upward slightly (either just before) or just as the correct number of taps was reached (1911, pp. 47-48), but he had no means by which to narrow the alternatives down any further.

Pfungst then demonstrated the animal's dependence on these signals. He showed that these signals were sufficient (though not necessarily exclusively responsible) for the control Hans's tapping. Pfungst asked the horse to count to 13 but leaned forward (in an exaggerated manner) until 20 taps had occurred without hesitation. Pfungst even showed that no question at all (but only the movement) was necessary to set Hans tapping (1911, pp. 56-57). He also demonstrated that the very rate of Hans's tapping depended on the degree of the questioner's forward inclination. In describing this latter effect, Rosenthal (1963) would later refer to it as a phenomenon of expectancy where a questioner (expecting a longer wait) would lean further forward for a large number and less so for a smaller number. Hans had somehow picked up on these human motor operations and modified his tapping rate accordingly.[11]

Evolutionary and Social source of Hans's abilities

The key to explaining how the details of this expectancy escaped the watchful eye of numerous scientific, professional, and lay-human beholders, lies in the evolutionary difference between human and equine eyes. This organic difference in the structure and function of the horse eye played a vital role in making Hans seem so clever. The eyes in human beings are both at the front of the head and close together. They are specialized for binocular vision. The horse, however, has two broadly spaced and immobile eyes placed on each side of the head. Horses rely on monocular vision in an extraordinarily wide plain of vision. As Fernald (1984) points out:

"Hans' large and motionless eyes served well to help satisfy his acquired desire for tasty delicacies and to hide the focus of his gaze from all human lookers. Even when approaching some distant cloth, he easily kept the slightest movements of his questioner well within his sight" (Fernald, 1984, p. 85).

In the concluding chapter of his monograph, Pfungst pointed out that such perceptual abilities are the sort of evolutionary adaptations which would likely be useful for the survival of wild equine species (i.e., natural organic selection). He also recognized, however, that Hans (as a trotting horse) was a product of selective breeding guided by human beings (i.e., artificial sexual selection). Hans, like many household pets, also lived under circumstances of total domestication (i.e., his biological and social needs were met through reference to human beings). In particular, von Osten (over seventy and lacking any immediate family) spent thousands of training hours with his equine pupil. Pfungst concludes with a statement regarding the bearing of the case upon "animal psychology in general" (p. 240):

"The proof which was expected by so many, that animals possess the power of [human-like] thought, was not furnished by Hans. He has served to weaken, rather than strengthen, the position of these enthusiasts. But we must generalize this negative conclusion... for Hans cannot without further qualification be regarded as normal. Hans is a domesticated animal....To be sure, in some respects they have become more specialized than their wild kin,...and in their habits they have become adapted largely to suit our needs. This latter [point] is shown by all the anecdotes concerning 'clever' dogs, horses, etc.... Though our investigations do not give support to the fantastic accounts of [human-like] animal intelligence..., they by no means warrant a return to Descartes and his theory of animal-machine (as is advocated by a number of over-critical investigators)..." (Pfungst, 1911/1965, pp. 241-242; emphasis added).

While Pfungst now considered the position that animal and human minds are not only quantitatively, but also qualitatively different to be experimentally confirmed, he also wanted to further understand the phenomena of expectancy as it is expressed in human-human relationships. Were the expressive movements of von Osten, Schillings, and others typical of human beings? If so, could a skilled observer learn to manipulate these signals in others? Would subjects in the laboratory become aware that they were sending such signals?

Laboratory Follow-up (Expectancy Effects)

Finished with the horse, Pfungst left the courtyard and returned to the University of Berlin laboratory to study expectancy effects in various face to face human situations. In the simplest scenario, volunteers served as questioners and Pfungst played the role of Hans. In the first tests, the questioner selected some number up to ten and concentrated upon it. Without knowing the number, Pfungst began to tap and soon found what he expected: a sudden involuntary movement of the questioner's head. This movement was later measured to be less than one millimeter in distance (as indicated by a kymograph attached to the subject's head). Twenty-three of his twenty-five subjects signaled consistently in this way, but when asked later, only rarely did they note any particular movement on their part.

In a more complicated task, new subjects were asked to concentrate on any one of six words: up, down, left, right, no, or yes. Each subject was free to think about the word in any way they wished and could even insert a "blank trial" on occasion (thinking of nothing in particular). Sometimes Pfungst answered by shaking or nodding his head, or by pointing in a certain direction, but often he simply said the word he thought the questioner had in mind. With 12 questioners and 350 trials, his score was 73% correct. Pfungst had learned to interpret the subtle social (i.e., inter-organismic) "expressive movements" of his subjects.[12]

The four directions (up, down, left, and right), were typically expressed by combined head and eye movements in these directions. Similarly, yes and no were indicated by nodding and shaking head movements while blank trials generally yielded no expressive movements. Importantly, these movements always took place when the subject began to think about a concept, and they occurred without the person's awareness or control. That is, they persisted unaltered even after Pfungst disclosed the secret of his successful guesses to the subject. Pfungst had now corroborative laboratory evidence for the types of "natural" signals noted to effect Hans's tapping in the courtyard experiments.

Pfungst, however, continued his laboratory experiment to provide clear evidence that "arbitrary" signals could be formed, superimposed on older ones, and even eliminated in favor of the original natural pattern. Arbitrary movements could be substituted for the natural ones (described above) by merely changing his own answering pattern (i.e., moving his arm up or down to guess the directions "left or right"). The transition in the subjects took some time. Subjects began with the natural right-left eye signals, but soon these were accompanied by the arbitrary (up or down) movements. Once this pattern was trained into a subject, Pfungst made 32 correct guesses in 40 test trials. His high hit rate was maintained even when he placed a blindfold on the subject and observed only the induced head movements.

Next, these arbitrary movements were reversed (i.e., Pfungst would guess "left" with a downward movement and "right" with an upward movement). After a dozen trials of this new system, the former arbitrary head movements were completely displaced by the still newer ones (i.e., totally the reverse). Finally, Pfungst ceased all arm movements, indicating his guesses merely by saying them (i.e., up, down, right, left, yes, no). The novel head movements continued for a time, then became more tentative, and finally disappeared. The collective summary of his combined research program was published in German as Das Pferd des Herrn von Osten. (Der kluge Hans) (1907).

Aftermath of Pfungst's research

Pfungst, subsequent to these studies, demonstrated that cavalry horses do not make good use of verbal commands from their riders (see Fernald, 1984). He also foiled the act of a clever German setter called Don by making phonographic recordings of this dog's "speech" and testing them on control subjects (Rosenthal, 1963; Krall, 1912). Von Osten, after some consternation regarding his own treatment at the hands of scientists, ceased to display Hans publicly and died in 1909.

Shortly afterward, Hans was moved to a farm and then sold to Karl Krall a wealthy jeweler from Elberfeld. Hans was soon back on public display with two other stallions (Muhamed and Zarif). These horses used inclined wooden platforms to tap out answers (see Katz, 1937). Wolfgang Kohler (another student of Stumpf's) saw all three horses perform and this inspired him to attend the 1912 conference of the Society for Experimental Psychology where Pfungst and Alexander Sodolowsky (an evolutionary biologist) squared-off on the issue of ape intelligence. Regardless of all such conservative scientific proceedings, however, Krall's (1912) book about the famous horses of Elberfeld retained its popular appeal.

The overlap between the empirical outcome of Pfungst's laboratory research and the much later operant behavorism (of Skinner) is noted by Fernald (1984) but the accomanying emphasis on the social realm of meaning in Pfungst's wider program is unfortunately severly underplayed. The details of Pfungst's inclusive empirical approach have been provided here because subsequent works (e.g., Kohler's Mentality of Apes, 1917/1925; C.L. Morgan's Emergent Evolution, 1923; Vygotsky & Luria, Studies on the History of Behavior: Ape, primitive and child, 1930/1993; and Leontiev, Problems in Development of the Mind,1959/1981) have utilized similar empirical and theoretical procedures to outline qualitative shifts in the phylogenetic, ontogenetic, and socio-historical realms of mentality. These and other works will be referred to later especially with regard to their direct bering on a transformative structure of animal and human mentality. The most pressing issue at present however, is to show that Pfungst's program of combined, ecologically valid research differed significantly from the pattern of research set down in contemporaneous (and subsequent) early American psychology.

Section Two:

The Loeb-Jennings Debate and Early American Comparative Psychology

No matter how conservative one might be while inferring "mind" from animal actions, there is always room to doubt. As Romanes (1882) suggested, an overly conservative attitude would lead to such skepticism not only in the case of lower or higher animals, but also in human beings. Pfungst (1911) mirrored this sentiment by pointing out that his investigations "by no means warrant a return to Descartes and his theory of animal-machine" (1911, p. 243). In the Americas, however, the greater part of experiments on animal activity had (from the late 1880s to the early 1910s) been carried out by physiologists not psychologists (see Demarest, 1987). Among this group of researchers, there was no shortage of overcritical investigators and this attitude reverberated in subsequent American treatments of the animal mind.

One of these physiologists, Jacques Loeb (1859-1924), had a direct impact on the shape of early American animal psychology by way of his experiments on so-called "forced movements" in invertebrates. In particular, his years at Chicago (1892-1906) and his debate with the more evolutionary minded H. S. Jennings (c.1900-1906) regarding the goals and methods of comparative analysis, effected both John Watson (1878-1958) and Robert Yerkes (1876-1956). Loeb was interested in control of animal movement, but Jennings was concerned with a more traditional exploration of the diverse mechanisms whereby organisms actively adapt to their surroundings.

It is these methodological implications rather than the empirical details of the Loeb-Jennings debate that have been brought wholeheartedly into the historical fabric of general psychology. That is, these two approaches to the study of invertebrate movements provided hints as to what might be done with the study of vertebrate and human mentality (Pauly, 1981).[13]

Much upset by the anthropomorphism of Binet, Forel, and others, Jacques Loeb openly questioned the usefulness of mentalistic language for the investigation of adjustive abilities in lower and higher organisms. He was much influenced in this methodological tact by Ernst Mach's portrayal of scientific endeavor as the pursuit of technical tools for the control of life problems rather than a search for absolute (general/timeless) truths.

Comparative analysis, Loeb suggests, needs to be extended only to the most notable conditions of an observable change without becoming overly concerned with the exact underlying mechanisms used by each particular species to accomplish this change. Loeb (1900), therefore, explicitly proposed a shift in the goal of comparative animal research:

"The aim...is no longer word-discussions, but the control of life-phenomena. Accordingly we do not raise and discuss the question as to whether or not animals possess intelligence, but we...work out the dynamics of the processes of association, and find out the physical or chemical conditions which determine the variation in the capacity of memory in the various organisms" ( Loeb, 1900, p. 287, emphasis added).

Loeb's concrete research program was adopted directly from botanist Julius Sachs who had previously identified and named heliocentric tropisms in plants (Pauly, 1981). That is, Loeb attempted to describe the so-called psychological processes of lower animals in terms of empirically identifiable and ultimately chemical-mechanical processes (Loeb, 1900). For him, Sachs's concept of tropism provided an alternative to both anthropomorphism and to the overuse of accidentally occurring natural selection to explain the conduct of organisms. His experiments, conducted between 1888-1891, involved exposing invertebrates to such external influences as light, gravity, chemicals, electrical shocks, and magnetic fields in order to "force" and "control" their movements.

Despite mounting opposition, Loeb's statements regarding the applicable domain of such tropisms continued to expand over the next twenty years. For example, in the latter chapters of his retrospective summary work Forced Movements, Tropism, and Animal Conduct (1918), Loeb argued that both the "instincts" and "memory images" of all animals could be understood as the "modification of tropistic reactions by hormones" (p. 157).

In the chapter on instincts, Loeb tactfully limits himself to evidence of chemotropic and heliotropic phenomena in insects and aquatic animals. But in the memory chapter, he somewhat unconscionably extends his analysis to humans and thus openly committed the second form of methodological excess mentioned at the beginning of this chapter section (i.e., psychophysical reductionism):

"The production of heliotropism by CO2 in Daphnia and the production of the definite courtship of the [human] male A for the female B are similar phenomena differing only by the nature of the hormones and the additional tropistic effect of certain memory images in the case of courtship. Our conception of the existence of 'free will' in human beings rests on the fact that our knowledge is often not sufficiently complete to account for the orienting forces..." (Loeb, 1918, p. 172).

A comparative zoological reply from Jennings

The most conspicuous objection to Loeb's approach was put forward by zoologist H. S. Jennings (1868-1947). Jennings had formerly studied under a Loeb devotee C. B. Davenport at Harvard, and attended a class by John Dewey at Michigan. He followed neither of these teachers however, and chose instead Ernst Haeckel (a recapitulationist) and Max Verworn (a zoological vitalist studying paramecia) as scientific models.

From 1899, on, Jennings argued that protozoan behavior was important methodologically because it provided support for the general theory of the origin and progressive development of psychic powers across the animal series. The organized study of "simple," structurally determined, "motor reactions" in lower animals might provide a basis for understanding the nature and development of "complex" behavior in more highly evolved species. Like Spencer, therefore, Jennings adopted both an associationist and a progressionist evolutionary approach to evolutionary analysis.

Jenning's attack on Loeb's application of plant tropisms to animals, was given fullest expression in his Behavior of the Lower Organisms (1906). As a zoologist, Jennings was more acquainted than Loeb with the structural and functional aspects of invertebrate motile activity. He was able, therefore, to point out, in fine detail, the oversimplifications and unsubstantiated generalizations in Loeb's work. In the place of passive tropisms, Jennings purported a neo-Lamarckian belief that active individual organismic learning was a major force in the evolutionary progression of adaptive instincts and habits.

For instance, the applications of noxious stimuli (such as tactile contact with a glass rod) to protozoa produce adjustable "trial and error" avoidance reactions. He reasoned (in a Haeckelian fashion) that if harmful situations lead to such "readier resolution of physiological states" for given individual organisms, they might over time cause variation in motor reactions of subsequent generations (i.e., natural selection of such adaptive reactions). His demonstrative figure portraying the "avoidance response" of his favorite subjects (paramecium) graced the pages of introductory psychology texts from 1904 up into the late 1920s (e.g., Dashiell, 1928).

In the place of Loeb's methodological call for pragmatic control of conveniently studied organisms, Jennings proposed a more comprehensive topographical survey of adjustive reactions in various species:

"[F]rom a discussion of...lower organisms in objective terms, compared with a discussion of ...man in subjective terms, we get the impression of complete discontinuity between the two...Only by comparing the objective factors can we determine whether there is continuity or a gulf between the behavior of lower and higher organisms (including man)" (Jennings, 1906, p. 329).

As shown in section three, this was just the kind long-term survey that the struggling new discipline of North American psychology did not have time for. So, despite their inexpensiveness for research, American "psychological" studies using lower organisms virtually disappeared shortly after the publication of Jenning's book.

Section Three:

Two American Comparative Psychologies

As Demarest (1987) has pointed out, the above debate produced two rather distinct comparative psychologies in America. Each addressed the methodological lessons of the Loeb-Jennings debate and each applied those lessons as best they could within the fiscal realities of early 20th century psychology departments. These two comparative traditions can be illustrated in the careers of John Watson and Robert Yerkes. Both psychologists carried out research on animals and human beings. Both also shared aspirations to systematize empirical investigation and to promote the discipline in wider society. However, their methodological approaches to the subject matter contrasted roughly along the lines of the earlier Loeb-Jennings debate.

Watson's overwhelming scientific concern was with obtaining generalized principles of prediction and control of experimental subjects. The grand opening paragraph in his famous behaviorist manifesto (1913) suggested that "psychology as the behaviorist views it.... is concerned with prediction and control of behavior," attempts "to get a unitary scheme of animal response" and "recognizes no dividing line between man and brute" (Watson, 1913, see also Watson, 1914, p. 1).

This was a considerable change from his earlier (more modest) claim that the behavior of rats warranted scientific investigation "regardless of their generality" (Watson, 1907a). These initial scholarly concerns were gradually replaced with system building to such an extent that his later use of human subjects (e.g., Watson, 1916, 1919b; Watson & Rayner, 1920) was largely a means by which he could demonstrate the ubiquity of "conditioned reflexes" in both infant's "emotional reactions" and in more "complex reactions", commonly called human thoughts (see fig 13).[14]

Figure 13 Watson's early animal and infant research. Watson first used albino rats in his dissertation research published as Animal Education (1904). The left panel shows one of his younger rats gaining entry into a specially constructed wire box containing food. Note Watson's novel modification of a reusable lever. Willard Small's previous study had used a cardboard trap door that the rats had to gnaw through (an altogether less reliable measure of "acquired habit strength"). The right panel shows Watson's research into the "emotional reactions" of newborn infants. This black infant's mother was a hospital wet nurse . Watson is forcibly immobilizing its head in order to emit the "emotion" of "Rage" -just one of four "instinctive" emotions (photo from Watson & Watson Psychological Care of an Infant, 1928).

Yerkes, on the other hand, while being concerned with experimental control, was primarily interested in carrying out a Jennings-like survey of various phylogenetic forms of mentality. He consequently castes his experimental net considerably wider than Watson (or any other early experimental psychologist) with studies on earthworms, turtles, pigs, gorillas, and chimps. It is vital to note, however, that while Yerkes included both human children and adults in some of these studies, his empirical work using them as primary subjects was confined to a relatively brief (yet important) period during W.W.I (coverd in chapter 4).

The contrasting aims and empirical practices of these two men can be seen in the content and intentions of Yerkes' writings between 1904 and 1932. Yerkes opened the century with a specific attempt to distinguish physiological investigation from psychological, arguing (among other things) that new empirical methods must be developed in order to tease out the psychological aspects of animal actions (Yerkes, 1904a). Similarly, his review of Watson's published dissertation Animal Education (1904) suggests the study of behavior and of comparative psychology are not identical endeavors (Yerkes, 1904b). This position was made more clear in his article on use of "objective nomenclature" in comparative psychology and animal behavior (Yerkes, 1905). His review of Watson's behaviorist manifesto also called attention to the importance of definitions in comparative psychology (Yerkes, 1913a; see also Yerkes, 1917b).

These critical discussions were accompanied (in Yerkes, 1916, 1917a) by a positively stated argument regarding the potential viability of investigating both human and animal "mental life" and "ideation." This argument was supplemented by various experimental demonstrations (e.g., Yerkes & Coburn,1915) of how this proposed investigation might be carried out (see fig 14).

Figure 14 Yerkes Multiple Choice apparatus. The upper panel shows a one of Yerkes' multiple choice experimental apparatus (photo from Boakes, 1984). It was used to test for "insightful behavior" in various species (in this case a pig). The apparatus was modeled from one used by Gilbert Hamilton (1911) one of Yerkes's former students. Hamilton had impelled each of his subjects to walk through the apparatus 100 times. The expected "hierarchy of intelligence" (i.e., farmhand, child, monkey, dog, cat) was found but the farmhand complained that the apparatus might drive people crazy. The bottom panel shows the later more subject-friendly modification used in subsequent human studies (photo from Valentine, et al., 1939). Similar species-specific modifications were also used on rats, monkeys, and gorillas. Ironically, while Yerkes' ostensible intent was to obtain information about the mental continuity and discontinuity across the wide phylogenetic scale, the multiple choice apparatus was explicitly intended to be a universal measure of the mentality of these species.

Here, and in his subsequent works (e.g., Yerkes, 1925, 1927; Yerkes & Yerkes, 1929), Yerkes was attempting to empirically prove that at least some forms of animal mentality are more than passive acquisition (or performance) of habits. In particular, he argued that by applying appropriate varieties of "the multiple choice method," we might be able to better understand how human mentality is similar and different from other specifically measurable forms of animal mentality (Yerkes & Coburn, 1915).

It was becoming increasingly clear that the same battle fought in physiology was now to be fought within the realm of early American comparative experimental psychology. This time, however, the apparent conceptual victory would go to the Yerkes/Jennings side (at least with respect to his treatment of human beings). In part, this was due to the historical intervention of W.W.I and the research/funding opportunities it brought comparative analysis of all sorts. However, while methodological behaviorism was eventually outlasted by this more broadly sweeping comparative methodology, the Watson/Loeb approach also had its era of research productivity and its disciplinary raison d'etre.

The rise of American rat psychology (J. B. Watson)

A trend away from a wide phylogenetic analysis began in America even while the Loeb-Jennings controversy was heating up (Demarest, 1987). One of the principal reasons for this narrowing of scope was the unavailability of academic positions, research funds, or lab space to American comparative psychologists in the first decade following 1900. Initially, both Yerkes and Watson lobbied for the establishment of American research stations and institutional laboratories in order to "study the evolution of the mind" (Watson, 1906). But by 1910, it was clear these pleas for funding would go unanswered.

The administrators and philosophers in the small denominational colleges, normal schools, and land-grant colleges, for instance, believed in a religiously motivated fundamental distinction between humans and animals and were not prepared to fund comparative research. Under these institutional circumstances, research emphasis usually shifted to the more attainable goal of comprehensive analysis of circumscribed problems in rather inexpensive but so-called "higher" organisms, typically the albino rat (Boakes, 1984; Demarest, 1987).

This new laboratory experimental animal becoming available to Americans in 1896, when Adolf Meyer, a young Swiss neurologist convinced Henry Donaldson at Chicago to use them for his studies on nervous system development.[15] It was Donaldson, in turn, who persuaded Watson to use rats for his dissertation research. Watson's experiments with albino rats were predated by Small (1900, 1901). Like Small, Watson's dissertation work used the time it took for each rat to get into a small box containing food as the measure of learned habit (see again fig. 14). He also used mazes that were simpler in construction than Small's earlier Hampton Court model.

The results of these more controlled experiments refuted the hypothesis that mylinization of the rat brain was necessary before learning of an experimental habit was possible. Very young rats (with little or no mylinization -as shown by post-mortem histology) readily learned to perform the tasks which Watson had devised. His work was published as Animal Education (1904) in which Watson agreed with Thorndike that trial and error learning of animals was little related to the "associations of the human mind," but was similar to the "human learning of motor skills." Numerous studies by others comparing maze learning in rats and stylus mazes learning in human beings would soon follow from this suggestion.

While the traditional evolutionary approach had focused on species diversity and variability, the increasingly radical animal psychology movement (between 1910-1938) openly treated species variability as error variance to be controlled and minimized during experiments (Wyers, 1987a). The contemporaneous changes in Watson's experimental focus and to his interpretation of results are indicative of this wider trend toward antievolutionary use of species.

Initially, Watson's PhD work raised (but did not answer) the important question of how the rats learned mazes. He then applied surgical techniques to test maze performance subsequent to systematic removal of sensory hardware from various rat subjects (including the whiskers, eyes, and olfactory bulbs of one unfortunate rat). Watson (1907a) portrayed the rat's maze performance as a chain of discrete responses controlled by kinesthetic feedback which become increasingly integrated as training continues. A subsequent study with his Chicago graduate student Harvey Carr (known as the Kerplunk experiment) lent even more weight to this "chain of responses" hypothesis. Once the rats were extensively trained to retrieve food at the end of a long arm of a maze, it was shortened by placing a barrier about half way along. When released into this shortened arm, the rats ran squarely into it and seemed to ignore the food located there (Watson & Carr, 1908).

At this time, Watson conceded that humans in the same situation probably use "ideational" means and "visual imagery" to navigate mazes. His subsequent works, however, increasingly portrayed even human learning as the development of "complex motor habits" (Watson, 1914, 1919a, 1924a, 1924b, 1930). In 1914, for instance, he asserted that thoughts and images are sensations arising from events outside the brain, these events being habits identical to other bodily actions except that they are more difficult to observe. Watson called them "implicit behavior" and suggested that what we call "thinking" is really sub-vocal speech:

"Now [if] it is admitted ...that words spoken ...belong really in the realm of behavior as do movements of the arms and legs....the behavior of the human being as a whole is as open to objective control as the behavior of the lowest organism" (Watson, 1914, p. 21).

In order to support his new radical argument, Watson (1914) begins with a summary account of animal sensory research to date (concentrating specifically on the experimental hardware developed by American psychologists since the turn of the century). Secondly, he outlines various techniques of observational field work (including his own work with noddy terns), followed by an account of maze learning in rats and other "acquired habits." Then, in an interesting chapter on the "limits of training of animals" he features verbatim accounts of performances by the Elberfeld horses. Watson had earlier favorably reviewed Pfungst's (1907) book on Clever Hans (Watson, 1908) and this is the likely source of his thought as subvocal speech hypothesis.

Watson follows this entertaining account with a brief (and perfunctory) report on the measured tongue movements while performing experimentally derived thought tasks as an example of "language habits in human beings." This latter evidence, while providing the primary "support" for his subvocal speech hypothesis, was also the most speculative and least data driven part of Watson's (1914) book. To his credit, however, he openly admitted the limitations of contemporaneous knowledge about such language habits. Finally, he sums up by outlining the implications of his approach to comparative general psychology. Watson's own career, and that of many later general psychologists certainly can be described as adhering to this outline:

"If the highly speculative position we have tentatively put forth here represents in any measure the true state of the case, it would seem that the field of behavior could be divided largely among three groups of investigators: (1) a group interested in the instincts, sensory and motor habits of animals below man, (2) another group interested in the same...in the human being, and finally (3) a group interested mainly in the language habits of the human being and in the possible development of such habits in the anthropoids" (1914, p. 334).

It is important to note why all of Watson's research (subsequent to his dissertation) was intended to be thoroughly antievolutionary and hyper-environmental. The mere fact of his environmentalism, of course, has been emphasized ad nauseam by countless textbook writers who quote the now most famous passage from the second edition of Watson's Behaviorism:

"Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist...doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors" (1930, p. 104).

What is not often mentioned, however, is the largely conciliatory tone of the passage which immediately follows: "I am going beyond my facts and I admit it, but so have the advocates of the contrary and they have been doing it for many thousands of years" (p.104). Ironically, it is in this line, and not in the preceding claim, that we gain significant insight into the contemporaneous state of American general psychology in which Watson's environmentalism was born.

In particular, Watson names both Arnold Gesell (an active eugenicist and an early "developmental" psychologist) as an example of the latter "evolutionary" trend. In other words, Watson had very good historical reasons for sticking steadfastly to an environmental interpretation of psychology. The obvious disciplinary alternative was unconscionable to him; especially because Watson's own studies on reactions in newborns clearly indicated that children of various races did not differ (Watson & J. Morgan, 1917; Watson & Rayner, 1920; Watson & Watson, 1928).

Thus, Watson's early rejection of the so-called "continuity theory of the Darwinians" (1914, p. 321) must be read merely as an argument against the haphazard eugenic application of mendelian genetics to human psychology. It must not, however, be read as an indictment of the continuity view of mind per se. In other words, his rejection of eugenics by no means blocked him from openly adopting another methodological excess (psychophysiological reductionism) which is de facto, a physiological continuity view. This latter position was certainly more consistent with the underlying similarity between Loeb and Jennings who would agree with Watson that "no new principle is needed in passing from the unicellular to man" (Watson, 1914, p. 318).

By keeping this in mind, it is easy to see why Watson (and not Yerkes who first reviewed the work) was the first American to suggest that Pavlov's principle of "conditioning" might be the means by which psychology is to bridge the gap between the behavior of animals and human beings (Watson, 1916). On both these counts (i.e., his anti-eugenics and his explicit reductionism), Watson's views contrasted increasingly with that of his colleague Robert M. Yerkes.

Pseudoscience and mental testing (R. M. Yerkes)

In contrast to Watson, Yerkes' animal research retained the more traditional Romanes/Jennings approach of studying comparative mentality throughout the entire animal series. His use of various species was accompanied by an explicit attempt to design experimental hardware that would elaborate both the quantitative and qualitative differences of mentality between species. This early theme of standardization of empirical equipment was also brought over by Yerkes into his differential psychology of human intelligence.

Before we can make proper sense of his overall approach to comparative mentality, however, there is an historical myth regarding Yerkes' approach to human psychology that must be surmounted. That is, it is often suggested that his largely careful methodological approach to animal research stands in marked contrast to his post-W.W.I approach to human mental abilities. It is also suggested that Yerkes somehow seriously compromised his own views of empirical method as an indirect means of obtaining funding for his long desired "animal psychology" laboratory (see Reed, 1987b).

I question at least part of these claims because Yerkes clearly held a eugenics approach to human comparison long before the war. Eugenics for instance was a prominent aspect of his Introduction to Psychology (1911). The prime example of this tendency, however, is his co-authored, applied eugenics laboratory manual for Harvard psychology students. This manual, called Outline of a Study of the Self (1913), was intended explicitly "to arouse [in psychology students] interest in the facts of heredity, of environmental influence, and in the significance of the applied sciences of eugenics and euthenics" (Yerkes & Larue, p. 2). It also requests at the outset that students file a copy of their "Record of Family Traits" with the Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor.

The predominant tone of the preface is one of paternalism and experimenter expectancy regarding the proper conduct of student participants: "Have your note-book revised, say, once a month, by the Instructor. Do not be afraid of offering your own explanations of the facts you obtain, -the Instructor can put you right if you have gone astray,..." (p. xvii). And further:

"If you follow these rules, every experiment will be seen to have its own proper place in a system of psychology....You will not see the reason for the choice of each particular experiment that the Course offers, any more than as a child you saw the reason for the particular sequence of rules in your English Grammar. But you should be able to see, at least vaguely, what it is that the Course is aiming at...." (p. xviii).

The rest of the manual puts one in mind of poor Clever Hans after his sale to Krall (who unlike von Osten did not spare the lash when the answers were "incorrect"). Consistent with the eugenics theme, these expectancies go well beyond one's conduct within the laboratory. For instance, after filling in the highly detailed, multi-paged, multi-generational, "Index to the Germ Plasm" (a pedigree chart regarding the physical, mental, moral, and social "traits" of ones family), the student is then asked to consider the implications of these facts on their eligibility for various vocations and for future marriage and procreational prospects:

"Is there a family vocation which attracts you?....For which you feel especially suited? In which you feel that you can maintain the family reputation? ....Give its history in the family, and justify your inclination to follow it or to choose some other. Have you any family traits which point you unmistakably to an hereditary calling?" (p. 21).

"Take up any prevalent diseases or tendencies to disease in yourself. Is there any sufficient reason or combination of reasons why you should not marry? Why you should not have children? If you are an excellent representative of high-class stock, is it not our duty to have as many children as you can successfully rear?" (p. 22).

Despite the ostensively progressive goal of the manual (i.e., to help build up "an analytical index of the traits of American families") we should not overlook the wider societal context and rather intimidating circumstances under which early psychology students were expected to perform. For instance, Henry Goddard, under the auspices of the United States Public Health Service, had recently began applying "mental tests" to the arriving European immigrants at Ellis Island, New York and had also published two books (The Kallikat Family, 1913a, and Feeblemindedness, 1914) as a result of his work at the "Training School" at Vineland, New Jersey. In these books, he argued that while many mentally deficient individuals can be trained for useful manual occupations, the overall level of intelligence was inherited and must therefore be a matter for national concern (see Allen, 1997).

When Goddard was first invited to Ellis Island in order to observe the procedures used by physicians to process the incoming immigrants, he found they were simply screening for the rather obvious physical signs of classic defectology (e.g., microcephlia, mongoloidism, and cretinism). In previously justifying the ongoing need for his Training School (founded in 1906), Goddard had already argued that "morons" (as the highest functioning of the "feebleminded" and as the real threat to society) were difficult to detect visually. They looked little different from the lay public; so only careful mental testing could weed out their undesirable germplasm before it was allowed to diffuse throughout the existing American stock (see fig 15).

Figure 15 Ellis Island mental testing. Starting in 1908, Henry Goddard's team of "mental testers," served to routinely limit eastern European immigration with special preference for rejecting those of Jewish background. In 1913, Goddard reported that of those tested to date, 83 percent of "Jews," 80 percent of Hungarians, 79 percent of Italians, and 87 percent of Russians were feeble-minded (1913b; see also Goddard, 1917; Smith, 1985). His clinical category of "moron" was quickly adopted in the wider legal and procreative control over American prison inmates, prostitutes, unwed mothers. While he recommended the "segregation and institutionalization" of these populations, other influential figures in the Eugenics Records Office (headed by biologist C. B. Davenport) actively lobbied for a more drastic form of control. Over 27,000 forced sterilizations were performed on American citizens between 1909 and 1938 (photo from Schultz & Schultz, 1996; see also Hilgard, 1979).

Similarly, in the year following the Yerkes & Larue manual, 1914, the First National Conference on Race Betterment took place. Working under the assumption that roughly 10 percent of the U.S. population was made up of "defective and antisocial varieties," they estimated that the incidence might be reduced to 5.77 percent by 1955, provided that approximately 5.76 million sterilizations were performed (Chorover, 1979, p. 46). Under such circumstances, would it not be foolish for a student to admit they were born of loose, unacceptable stock? Above all, who would dare suggest that they could neither see nor agree with "the system of psychology" presented therein?

To do so would have landed the student in a similar predicament as the patients of the contemporaneous Sigmund Freud. No matter how politely one might be treated, any denials or detractions would simply confirm the analyst's (or experimenter's) pseudoscientific hypothesis. Throughout the 1920s, psychology students routinely traced their own family trees as a requirement for the eugenics sections of general psychology classes taught at Harvard, Columbia, Brown, Cornell, Wisconsin, and Northwestern (Guthrie, 1976, p. 81).

Bearing in mind that the eugenic treatment of human mentality was a constant societal backdrop for the early animal research, it should not be surprising that Yerkes' successive efforts to experimentally establish a stepwise phylogenetic "mental ladder" (i.e., different grades or kinds of mentality in different animals) ended up being structurally compromised by an implicit continuous "mental chain" view of evolution (Candland, 1993). As Yerkes (1943) would later put it:

"[T]he behavior of chimpanzees as revealed by string, box, selective transportation, multiple choice, and many other sorts of problem experiments affords varied evidence of what I have tentatively termed "ideational processes." I think of it as an appearing neural process from which human insight, full-fledged and unmistakable, has developed" (Yerkes, 1943b, p. 400).

Surmounting a false dichotomy:

Mental continuity vs. rickety ladder theories

While Watson's rat psychology attempted to negate the mental gulf between animal and man (by treating human mentality as if it were no different from rat mentality); Yerkes attempted to close the mental gap (by bringing our understanding of the ape's mind closer to that of our own). Ironically, both these comparative approaches can be viewed as antievolutionary if we understand that mental evolution works upon the same principles of continuity and discontinuity which organic and cultural evolution work upon.

In particular, the altogether more evolutionary approach, exemplified in this chapter by Pfungst's treatment of the clever Hans phenomena, takes a different methodological tack. It addresses, head-on, the qualitative differences between the organic and social genesis of observable mental abilities of animal and human beings. Here was the rudiments of a non-additive approach which would not denigrate the various levels of animal or human mentality which it described. Unfortunately, despite their common reference to Pfungst's work, neither the Watsonian, nor the Yerkes forms of comparative psychology took up his larger (social) unit of analysis.

Both of the traditional approaches to comparative psychology (one stemming from Watson and the other from Yerkes) are deserving of the term "modern" because they applied measurement devises to psychological phenomena. Neither, however, are significantly revolutionary (methodologically) to earn the status of "progressive accounts" if we are to be at all conservative with that phrase. Even the Jennings/Yerkes approach (of wide phylogenetic analysis) was, at best, a statistical revision of the older Romanes (1882, 1888) equivocal mental continuity position (where culture is merely added to the individual and social levels of animal mentality).

While his empirically supported inferences about the internal "ideational" states of animals and his appeal to a broad evolutionary naturalism set Yerkes' comparative psychology apart from Watson and others, it never in fact provided the explanatory synthesis he had hoped for (largely because Yerkes routinely conflated organic, mental, and cultural evolution). The best such a combined phylogenetic/ontogenetic research project can do is to provide occasional concrete descriptions of particular cases (e.g., Watson's noddy terns experiments, Yerkes's later observational overviews of chimpanzee mentality). At worst, as was more often the case, mere phylogenetic (within apparatus) comparisons were carried out and the result was merely a more elaborate form of abstract generalization (e.g., the vast majority of rat and human maze studies).

The problem with subsequent North American comparative psychology has not been, as is often claimed (see Beach, 1950), its mere overreliance upon common associationist concepts such as instinct, drive, or conditioning. Rather, the major problem has been that mainstream psychologists are entirely too slow to recognize the viable set of alternative analytical categories implied when one takes a wider social-societal unit of analysis as a starting point for comparative research.

Conclusion

The overall relationship of this chapter with the prior one and with chapter 4 (which is provided after the historical bridge of chapter 3 concerning American public eduction) can now be stated. Whether the continuity view of mental evolution is analytically expressed (1) functionally through postulating identical "emotional expressions" in species (e.g., Darwin, Romanes); (2) physiologically, through teasing out identical "emotional reactions" (e.g., Watson); (3) biographically through working out a "student index of the germ plasm" (e.g., eugenics courses); or (4) statistically through correlating scores in either (a) standardized multiple-choice apparatus -designed to measure "insightful behavior," (e.g., Yerkes) or (b) stanardized mental tests -designed to measure "latent intelligence" (e.g., Yerkes, Terman, Wechsler, etc.), it is present all the same. This continuity view has therefore heavily influenced the subsequent course of general psychology and ability testing. It has also frustated successive attempts to work out a non-reductive mental ladder (a.k.a. intellectual heirarchy) upon which further empirical research, testing, and intervension progams could be based.

As the opening section of this chapter (i.e., on Pfungst's investigation of Clever Hans) has suggested, only by recognizing the wider phylogenetic, ontogenetic, and socio-historical continuities and discontinuities of mental evolution, can this early collective empirical evidence be recontextualized and reused as a source of corroborating evidence in a more explanatory account of our subject matter. Standing alone, however, the methods of data collection and the conclusions drawn by proponents of this early rough science remain highly questionable.

[7] Ethel Tobach's (1987) edited volume was invaluable for preparing this chapter. It contains wonderful articles by Tolman, Wyers, Cadwallader, Demarest, and others. Fernald's The Hans Legacy (1984) and Boakes' book on "psychology and the minds of animals" (1984) have also been helpful.

[8] This correlation of skull size and intelligence had also been used in 1874 by Francis Galton who attempted to correlate the recorded hat-size measurements from eminent English scientists with a variety of other psycho-physical measurements (see Fancher, 1997).

[9] Fernald's wonderful account (of Pfungst's research) is paraphrased rather extensively in this section. I argue, however, that these details show just how different Pfungst's experimental approach to comparative mentality was from the two usual North American approaches practiced today (cf. Fernald, 1984). Like Fernald, however, I am much more favorable toward Pfungst, and comparative psychology in general, then some of the most recent critics have been (e.g., Candland, 1993).

[10] It should be noted here that Candland's (1993) mobilization of "inferential statistics" to point out that Hans always overtapped when he was incorrect in such control trials should not be used by modern readers to play down Pfungst's accomplishments in conducting the Clever Hans investigation. As seen later in the "Intelligence testing" section of this work, the use of advanced statistics is no guarantee of relevant research. It only stands to reason therefore that the lack thereof (especially when we are considering older research) should not necessarily be treated as an obstacle to investigative elucidation.

[11] Rosenthal (1965) offers many examples of subsequent research in this vein. Fernald (1984), however, uses an operant behaviorism approach to analyze both the training (of which we actually know very little) and actions of Hans. This interpretation however, unwarrantably portrays a social phenomenon as if it were merely an additive set of individual phenomena.

[12] The term "emotional expressions" is a direct reference to Darwin's (1872) work and was modified later by Watson & Rayner (1928) as "emotional reactions."

[13] With respect to the debate regarding E.L. Thorndike as "the founder" of American comparative psychology see Cadwallader, 1987 and Demarest, 1987 vs. Dewsbury, 1984.

[14] In the intervening years between his earliest postdoctoral research on the "behavior of noddy and sooty terns" carried out under a Carnegie foundation grant (Watson, 1908), and his last book on The Psychological Care of Infant and Child (with R. Watson, 1928), Watson had carried out a sly public relations campaign in the pages of the New Yorker magazine, the New York Times, and in Harpers monthly under the pen-name "Mr. Psychology." These articles helped obtain vital private contributions for a behavioral research fund and from the Rockerfeller Memorial. Even his lucrative post-academic carrier in advertising was concerned with prediction and control.

[15] They had been used in European physiology labs since 1860s.