Chapter 3

American Schooling, Administrative Reform, And Individual

Ability Testing:

Assimilation and sorting before World War I.

Paul F. Ballantyne

After their late-19th century European debut, mental tests of various sorts were either translated and Americanized, or produced from scratch and put to work in a rapidly changing 20th century school system, military, and industrial economy. In particular, the assimilation and sorting roles played by the American public school system figured prominently in the timing, shape, and uses of early individual mental testing techniques. This chapter traces the changes in the structure and function of American schooling from the 1890s up to World War I and answers why educators were so receptive to the introduction of testing technology for sorting school children.

Chapter Overview

Section one covers the era of Progressive School Reform (1890-1917) with its cultural changes caused by industrialism, immigration, and legislative reform (e.g., school attendance, child labor laws). Section two highlights a period from 1900-1920 in which the institutional and functional aspects of modern public schools were first worked out. The transition from rural one-room school houses to a so-called "consolidated" (Kindergarten through grade twelve) school system was one important result of this period. The emphasis on "school efficiency" after 1910 and the emergence of a distinctly modern hierarchy of school management are also mentioned. In section three, the contemporaneous debates and institutional bases formed by so-called "experimental" progressives (Dewey, Kilpatrick) versus those guided by more "assimilative" or economically driven pedagogical motives (Thorndike, Cubberley) are summarized.

Section four examines the traditional mental sorting function of early 20th century public schools. The fledgling attempts to translate, apply, and produce so-called individual "intelligence and achievement" tests that perform the function of sorting students prior to World War I are covered. Lewis M. Terman, based at Stanford University, figures prominently in these initial attempts. While his explicit motives for carrying out such research contrast with those expressed by Alfred Binet, the underlying assumptions about the individual nature of human intelligence are noted to be very similar. It is suggested that this assumption provided a problematic starting point for modern American ability testing.

Section One:

From Common Schools to Progressive School Reform

The prehistory of what would become the 20th century American public school system began with a long evolution of various forms of colonial one-room schools (e.g., Dame, Latin Grammar, and Academy schools) into the district-based, Denominational and "common school" systems. In colonial New England, efforts were directed at establishing district and then state-sponsored common schools that carried a clear religious mandate.[16]

By the early 1840s, Horace Mann was making significant headway by arguing that publicly funded education would provide the means by which working class and lower middle-class children could achieve economic and societal stability.[17] The message was well received by some workingmen's associations because they had already established reading rooms, libraries, and even schools for their members (see Hogan,1978; Reese, 1981). They now recognized the common school as another likely means of creating improved social and economic conditions for their members (Gutek, 1986).

Common schools, throughout America were ostensibly intended to be available to all children and to be based on nonsectarian morality. The harsher reality, however, is that urban common schools in particular were established and maintained by politicians to protect things as they had been. They were set up in the 1840s to protect against Irish Catholics and German immigrants in New York and Chicago. They were set up in the 1850s (after the Mexican-American war) to protect against the Spanish-speaking residents of Los Angeles. They were set up and then formally segregated in the 1880s to socially contain the descendants of freed slaves in Charleston, South Carolina (see Callahan, 1962; Cremin, 1965; Katz, 1968, 1971). These ulterior motives meant that the quality of common schools varied greatly -from being moderately adequate to being contemptuous insults to the ideals of American democracy.

Protestant paternalism, in particular, was motivated not only by capitalist zeal but by an older Calvinist inspired social gospel belief that being rich is a sign of God's approval and that being poor indicates his disapproval. As Mosier (1965) points out, common school textbooks such as McGuffy's Readers (in widespread use between 1836 and 1890) were replete with this message.

Within the context of this gospel of wealth, the poor took up a paradoxical position. On the one hand, their very existence was recognized as an inevitable and therefore acceptable part of the social economic order. On the other hand, they were individually expected to escape poverty by being industrious, thrifty, and moral. The best examples from McGuffey's Newly Revised Eclectic Second Reader (1843), are two successive stories in having the titles The Rich Boy and The Poor Boy.[18] Certainly a child reading the first story would conclude that God is just and that this boy deserves to inherit his parents' wealth. Similarly, a child reading The Poor Boy might conclude that poverty is good because of its positive effects on moral fortitude.[19]

These two stories provided common school children with a justification for economic inequality and with a rationale for accepting one's position in life. Poor boys might have been pleased to learn that they could be happy if they were good and that they were free of the extra burdens or responsibilities of the wealthy. Rich boys might also have been pleased to learn that their good fortune was a blessing from God and that piousness on their part merely required that have the fortitude to patronize the more worthy poor and to exploit the less worthy. As Spring (1994) points out, the McGuffey Readers were clearly designed to reduce antagonisms between the rich and poor classes. For the virtuous, consciousness of one's particular social class was to be accompanied by consciousness of belonging to the more general class of humanity.

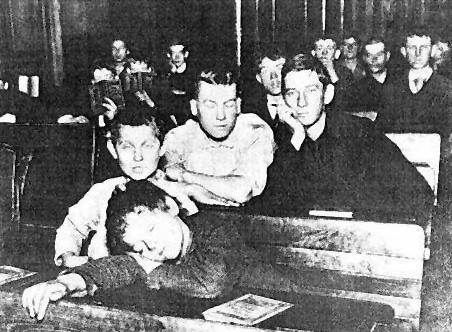

By 1890, most local boards (outside the South) certainly conceded the ideological importance of public schooling for all children but the actual physical and functional conditions in urban neighborhood common schools (where building, hiring, and maintenance was done on a patronage basis), still left something to be desired. In How the Other Half Lives (1890), Jacob Riis brought attention to the unhealthy living conditions of immigrants and argued that the continuing success of corrupt party-machine politics sprang from unstable urban homes, poor schools, and unhealthy physical environment (see fig 16).

Figure 16 Schoolroom in New York's Lower East Side c.1886. Mistrust, boredom, exhaustion, and confusion are all shown in this typically heterogeneous collection of boys varying in age, culture, and schooling experience. Note the two boys upper left shielding their face from the camera. "In New York we put boys in foul, dark class-rooms, where they grow crooked for want of proper desks, we bid them play in gloomy caverns which the sun never enters,... and in the same breath illogically threaten them with jail if they do not come...." Riis wrote (photo from Edwards & Richey, 1963).

The fact that the social reform movement was aimed specifically at the living conditions and lack of assimilation of the poor, was cause for considerable resentment. Arguably, the whole system of machine politics and the social consequences thereof were, in fact, maintained by the rise of late-nineteenth century industrial trusts (a.k.a. business monopolies such as Rockerfeller's Standard Oil Company and the Carnegie steel empire).

Similarly, in line with the doctrine of the gospel of wealth, initial common school reform tried to encourage poor children to become more like those routinely exploiting their parents. Faced with a "choice" between a common school system that utilized paternalistic teaching tools and the familiar parish funded Catholic schools (set up out of necessity between 1830 and 1890), Irish and Italian working class families were left with little choice at all (Munnich, 1936, Gabert, 1973).

It was these social conditions and educational concerns which formed the basis for the so-called Progressive School movement (of Horace Mann and others) designed to improve the availability and adequacy of schooling to all American youth. Successive expansions of publicly funded schools eventually led to the establishment of formalized teacher training and by 1890 to the founding of "experimental schools" (e.g., Columbia and Iowa) designed to test the veracity of various educational methods. Higher education too underwent significant changes to its institutional basis, curriculum, and its availability.

Progressive School Reform (1890-1913)

While the traditional local, regional, and denominational battles over the content and funding commitments of common schools would continue, the need for organized school reform was particularly great after 1890 when the so-called forces of modernization (i.e. urbanization, immigration, and industrialization) combined to form what is known as the progressive era of American history (1890-1917). Successive modernization of both public school facilities and curriculum took place during this era essentially because they were necessary to: (1) meet the changing needs of business; (2) address the increasingly heterogeneous requirements of non-Protestant cultural assimilation; and (3) to simply produce institutional compliance with revised Child Labor and School Attendance laws.

Schooling and Industrialism

Beginning at the time of the Civil War, American education became increasingly focused on issues related to industrial and technical training. In the case of higher education, the passage of the Land Grant College Act (or Morril Act) in 1862, provided a perpetual endowment for vocational schooling. California, Ohio, Arkansas, and West Virginia used the money to establish state universities with agricultural and engineering programs. In Connecticut, the money was used to endow the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale. In New York, special funds were provided to Cornell for the establishment of its agricultural and engineering programs. A similar program was also set up in Indiana at Purdue University (Button & Provenzo, 1983).

Programs in art education (essentially the training of skilled draughtsmen for industry) had first been established in Massachusetts during the late 1860s. Rather than following the traditional apprenticeship method in which a student learned a trade or craft by copying the work of a master, students now learned the basic principles of design and fabrication that were the basis of the manual or mechanical arts.[20] By the late 1870s widespread interest in "industrial education" began to develop throughout the United States. College curriculums had also undergone increased breadth due to the Land Grant Act of (1862). For instance, Josiah Pickard, the Chicago superintendent of schools from 1864-1877 and the first president of the National Education Association (NEA) had recently became a professor at the University of Iowa and established the first university courses in Education in the United States.[21]

It was becoming clear that the traditional craftsperson or farmer, no longer possessed the relevant skills to pass down to sons or apprentices. Thus, the labor force that modern industrialization required was initially comprised of journeymen whose skills were obsolete; of former farm laborers who were supplanted by mechanization; and of Southern Negroes and Whites who came north seeking work. Increasingly though, the need for unskilled industrial hands was only satisfied by tapping the growing pool of non-Anglo immigrant workers.

Immigration and the cultural hierarchy

Between 1870-1920, the U.S. population nearly doubled from 63 million to over 100 million, and much of the population growth came from immigration. In one of the largest mass movements of people in history, approximately 28 million immigrants arrived in the U.S. so that by the twenties more than one-third of the population was either foreign-born, or children of the foreign-born. Half of these newcomers were from Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe, bringing with them a host of different language, religion, food, work habits, and other cultural traditions (Chapman, 1988). The older waves of immigrants had been for the most part Anglo-Saxons, Germans, and Scandinavians but by 1900, most immigrants were Italians, Poles, Hungarians, Slavs, and Russians.

The change in the source of immigration, from the industrialized north and west of Europe to the agrarian south and east, meant that the newer immigrant faced greater difficulties in fitting into the industrialized workplace and the modernized school system of the American landscape (Baritz, 1960). At this time, a relatively stable cultural hierarchy of power between owners, managers, industrial workers, and unskilled labor was being established. Rich businessmen and Protestant politicians were at the top followed by other landowning Protestant citizens; landowning Catholics, Jews, and skilled laborers took up the lower middle ground; and the "inferior races" as then defined -Blacks, Chinese, and "Indians"- (landowning or not, educated or not) were at the bottom. Only indigent children received a lower status as they were clearly more exploitable than even the bottom rung of the above hierarchy.

School attendance, child labor, and adolescence

Compulsory school attendance was first established in Massachusetts in 1852. The spread of such laws quickened after the Civil War so that by 1900 they were on the books in 30 states; by 1910 in 40 states; and by 1918 in all states. Enforcement, however, was only regular after World War I, when state governments began consolidating their jurisdiction over existing local school systems (Rothstein, 1994). This situation provided ample opportunity for entrepreneurs to "employ" children in backbreaking and dangerous work from the age of 5 upward. The National Child Labor Committee (N.C.L.C.) was organized in 1904 and numerous books and articles in national periodicals such as The Survey, The Outlook, McClures's, and The Independent describing the conditions of child labor in America. Of particular note was the work of Lewis Hine.[22]

There also began a wider appreciation of how changes in cultural-historical forces were changing the very nature of North American childhood development (and, therefore, the typical pattern of educational requirements). In particular, G. Stanley Hall in Adolescence (1904) noted that unlike earlier times, when children at the onset of puberty were expected to enter into the responsibilities of adulthood, an intermediate period of transition (called adolescence) was increasingly part of the normal development of American children. Modern technology had actually extended the period of the typical childhood learning period up into the late teens (see Demos & Demos, 1969; Bremner, 1971; Kett, 1977).

At this time some educators, inspired by the work of Hall (1904, 1911), sought a system of educational reorganization that would facilitate a student's transition from childhood to adolescence. Noting that the seventh and eight grade curriculums were often too repetitious with that of earlier grades, they suggested an earlier introduction of either academic subjects or vocational training. A variety of plans for doing so were tried but eventually, a general trend toward a six-year elementary school, a three-year senior high school, and an intermediate school -the "junior high school" program, composed of the seventh, eighth, and ninth grades was adopted (see Briggs, 1920; Koos, 1920; Bossing & Cramer, 1965; Gutek, 1986).

This new curricular structure of schooling occurred in conjunction with the recognition of the "sorting function" of modern schools. It also provided an convenient rationale for the gradual adoption of psychological tests and systematic vocational guidance. It is therefore worthwhile elaborating upon the changes to the functional and physical implications of school reform as they related to both rural and urban settings between 1890 and 1920.

Section Two:

Modern Schools: Structural-functional aspects and professional debates

Between 1890 and 1920, both the explicit goals and the physical conditions of public education in America underwent significant change. In the 19th century, the explicit goal of schooling was to provide both minimal literacy and ethical standards to most students while cultivating a small elite for high school or college. As the work of youth was needed less and less, however, enrollment in elementary school (and high school) began to increase dramatically. In 1890, only 6% of eligible age group went to high school and only 10 to 20 percent of those actually graduated. Finally, only 2% of the eligible age group went on to college. By 1900, however, 78.7 percent of the population between five and seventeen attended school; and by 1926, this figure had jumped to 90.4 percent.

This section summarizes the attempts of Administrative reformers to make the modern public schooling system more economically efficient. Most importantly, by the early 1920s, the expansion of graded "consolidated" schools into rural areas and the eventual emergence of the now familiar system of primary, junior, and senior high school system was well under way. Contemporaneous debates between the new class of educational experts also had profound implications for the curricular structure and the sorting function of modern schools.

Administrative Reform:

School curriculum and educational efficiency

With increased mechanization of the workplace, the requirements for those who would be going on to high school and college would have to be sporadically adjusted. But the basis for that adjustment was not clear either from any contemporary theory of learning point of view or from an administrative point of view. In gradual and halting steps, a shift occurred away from the traditionally rigid high school curriculum (based on faculty psychology of instinct, habit, and reason); to an interim geographically varying curricula (along the lines judged best for each community -urban, rural, affluent, or economically depressed); and only then toward a more centralized or nationally standardized set of curricula ostensibly designed to meet the requirements of a wider administratively efficient modern democracy.

Conservative curriculum changes (1890-1910)

Prior to 1890, three traditional high school programs were in place but only the first of these (the Classic language curriculum) was intended for those continuing on to college. The second curriculum of study, English literature, was intended for those wishing to be civil servants or journalists; and the third, "normal school" program was intended for those planning careers as teachers. One report that partially broaden the scope of those who would continue on to college was the Report of the Committee of Ten on Secondary School Studies (1893). This was a National Educational Association (NEA) committee consisting of : 5 College Presidents, 1 professor, 2 private schoolmasters, a principal of a public school, and the incumbent U.S. Commissioner of Education (see Rippa, 1971).

One of the members, Charles Eliot was the long-time president of Harvard University who had already successfully broadened his university's curriculum by putting in place an "elective system" that operated from 1869 onwards. As a promoter of educational reform, Eliot had considerable experience with combating the traditional doctrine of mental discipline. That doctrine, utilized an old Faculty Psychology "mental muscle" metaphor to argue that persistent mental exercise in certain topics (such as Greek, Latin, and Arithmetic reasoning) was especially generalizable to other areas of life and should be favored in the curriculums of higher education. In other words, that which was best for the preparation of the college scholar, was also best for the preparation of all youth. Eliot called upon his own experience at Harvard and suggested that nearly all subjects had value in this regard (as long as they were taught in a manner that attempted to cultivate reason and morality). In other words, the restrictive traditionalist rationale regarding high school curriculum's and college entrance requirements had no practical foundation and should be dropped.

The Committee, however, was only partially swayed by Eliot's arguments and a compromise solution was produced. They simply advanced an expanded list of topics believed to be of value for disciplining the mind. Nine broad subjects were suggested: Latin, Greek, English, modern languages, physics and astronomy , chemistry, natural history, history, and geography. The inclusion of science courses in the list was unconventional for its time and was likely the direct result of Eliot's influence (see Tanner & Tanner, 1990). The assumptions of Faculty psychology, however, also survived in the recommendations as to the manner and frequency with which these topics were to be taught. First of all, the assumption of the universality (to one degree or another) of a given set of mental faculties that would either be allowed to mature, or not, by a given school structure was present.[23]

Secondly, the old mental muscle metaphor (dealing with fatigue and power) was present in the Committee's policy of extensive study, on the part of any individual student, in only a relatively small number of subjects:

"Selection for the individual is necessary to thoroughness, and to the imparting of power as distinguished from information; for any large subject whatever, to yield its training value, must be pursued through several years and be studied from three to five times a week" (Quoted in Edwards & Richey, 1963, p. 550).

Thirdly, the striving toward standardized measurement was also present in the administrative recommendations for implementation offered by the Committee. High schools, they suggested, should not only widen the available curriculums and introduce an elective system, they should also define a unit of instruction in terms of the number of hours of instruction given per week in each subject at that school. The latter unit would then be used by prospective college acceptance boards to decide on the acceptability of their graduates for admission.

Further impetus was given to the development of a standard unit for the assessment of high school curricula by the Report of the Committee on College Entrance Requirements (1899), which requested that colleges "state their entrance requirements in terms of national units, or norms." Soon afterward, too, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching would finally defined a unit as a course of five periods a week throughout an academic year (see Edward's & Richly, 1963).

While it is clear in hindsight that The Committee report was a turning point in the history of the public secondary education system (as a movement away from local concerns and toward national standardization), it must also be remembered that at the time, public high schools were still intended for a relatively homogeneous group of upper middle class children with predominantly Anglo-Protestant backgrounds. The progressive aspects of the report were designed specifically to cater to the updated requirements and interests of that homogeneous group.[24]

Just as the Committee of Ten published their report on high school curricula, another NEA report mandated to assess the elementary education curriculum (and known as the "Committee of Fifteen, "1895), was just wrapping up.[25] The chair of the new report, however, was William Harris, then U.S. Commissioner of Education. Harris was an outspoken proponent of traditional liberal arts education. He believed that the best way to transmit and maintain the cultural experience of the nation was to concentrate on five central academic areas (grammar, literature and art, mathematics, geography, and history) which he likened to the five "windows of the soul" (Harris, 1888). The report, therefore, while supporting the inclusion of a course dedicated to "Natural Science and Hygiene," also suggested that all new courses should simply be added to the time devoted to more traditional work (see Tanner & Tanner, 1990). This support for the status quo, helped solidify the position of traditionalists within the NEA for the next two decades and as enrollment rates of children with varied backgrounds climbed, so too did the failure rates.

Eventually, however, it became obvious that many of the children attending even the lower grades of public schools were not progressing steadily. By 1909, for instance, Laggards in Our Schools, written by educational reformer L. P. Ayres, focused national attention on the problem of school failure. Ayres suggested that a third of all school children were somehow "retarded" in their progress due to late entrance, irregular attendance, illness, physical defects, or lack of geographical mobility. He then proposed a twofold plan of educational reform: (1) better enforcement of compulsory attendance laws; and (2) curricular reform in order to provide both special classes and a wider curriculum to fit the abilities of the average (non-college bound) pupils. These proposals, and similar initiatives by earlier figures such as Jane Addams, Ellen Gates Starr, and Jacob Riis, were the ideological backbone of the shift from isolated urban neighborhood school houses toward modern "comprehensive" school systems.

Centralizing the urban schools

In the progressive era, the centralization of city school boards usually entailed a shift of administrative authority from each individual neighborhood school to control by the next highest level, a local school district. In the nation's largest cities, however, power moved from Ward Boards (already in control of a number of neighborhood schools) to citywide school boards. Most often, centralization was imposed upon ward boards and their administrative agent, the ward trustee, by professionally trained administrators with political connections to the conservative Republican party. They argued the schools were rife with corruption and were therefore unable to educate their students efficiently.[26] These, reformers sought to give citywide boards of education more power over teacher hiring and firing, building construction, maintenance, and textbook selection.

Neighborhood or Ward board members, were often local small businessmen (e.g., tavern owners, tailors) with day-to-day contact or first-hand experience with the religious and cultural practices of their constituents. The new policy makers, however, were usually expected to be elected on a citywide basis and they tended to be from the commercial and professional classes: manufacturers, bankers, doctors, lawyers, and real estate men (see Nearing, 1917; Counts, 1929). This latter group could hardly be expected to represent fairly the interests of the laboring masses of the cities and with the movement toward centralization, urban public schools became less and less schools of the public.

Similarly, the centralization of city school boards was a direct threat to the established work pattern of urban school teachers. Most of these teachers were women who had been hired under the rules of the ward system, which emphasized who one knew in the community.[27] New qualifications for entering teaching were introduced and also imposed upon experienced teachers to prevent their promotion. Further, "regularized" salaries involved cuts or freezes as often as they meant raises for teachers and this led to the formation of teacher associations usually in opposition to the new boards and superintendents (see Urban, 1982; Urban & Wagoner, 1996).

Consolidating the rural schools

Similar changes to rural demographics promoted the establishment of consolidated school districts. As the Midwestern and Western territories were settled thousands of local districts, many of which had but one school, had been established. Although late-19th century state officials and professors of education in Eastern Normal schools routinely argued that these small districts were fiscally inefficient, local districts often preferred to remain as autonomous from state control as possible.

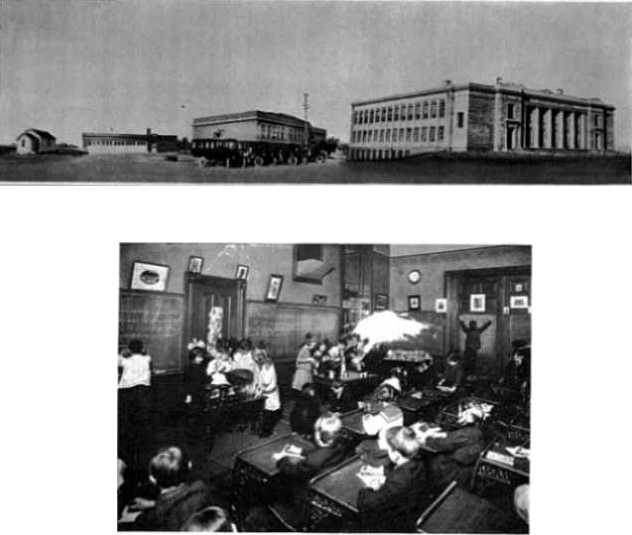

It was only in the early 20th century that consolidation began to accelerate. Gutek (1986) points out, three changes that made the specific movement toward rural consolidation possible: (1) a decrease in the number of farm families, which made it difficult to maintain one-room schools; (2) improved transportation and roads, which facilitated the busing of students to larger consolidated schools; and (3) financial inducement in the form of larger grants-in-aid from state governments (see fig. 17).

Figure 17 Rise of the Consolidated Schools. The upper panel shows the Johnstown Consolidated School, Colorado (c. 1924). Typically such schools had twelve grades in a three-story red brick building with electricity, running water, toilets, central heating system, and a daily janitorial service. The main building was augmented by an annexed manual training shops, gymnasium, an auditorium used by the community, and a garage for the busing fleet. Moving picture machines and separate public library facilities were also commonly available. In the above case, the original one-room building (far left) is literally eclipsed in terms of both size and also in its functional relationship with the community. Not only did a greater proportion of school-aged children now participate in formal education, but they were also schooled in a decidedly different manner. The lower panel, for instance, shows pupils actively working on the units of measurement in an age-graded consolidated school classroom. The predominant teaching techniques were a pragmatic admixture of both traditional assimilative indoctrination and more progressive child-centered pedagogical approaches (photos from O'shea, 1924).

Age-graded classrooms

Graded classrooms, too, were good for school administrators. Since each class of children could be considered as a homogeneous group, the size of such a group was rendered less relevant and more students could be accommodated. Graded classrooms were also viewed as good settings for teachers. In theory, since teachers no longer needed to teach children obviously differing in academic experience the older one-by-one recitation could be abandoned. More group endeavors could be carried out and the same lessons could be taught to the whole class simultaneously. On the practical side, standard workbooks and textbooks allowed youngsters to do the same work at the same time, and this made them desirable for overcrowded classrooms. Regardless of whether the emphasis in any particular classroom was on assimilation or on child-centerdness, the major disadvantages to age-grading remained the same: (1) students could no longer advance through the system at their own rate; and (2) they tended to lose contact with both older and younger students.

Hierarchy of Superintendents

The drift of school administrators toward "business" methods started in earnest with two books by W. E. Chancellor (1904, 1908) which portrayed the city superintendent as a business manager.[28] Ellwood Cubberley's Public School Administration (1916), the most widely used training textbook for many years, would strike up a popular balance between the cost accounting and scientific management factions but would also portray the superintendent as captain of the schooling industry. This updated approach still left school teachers with little authority outside the classroom.

As the twentieth century wore on, local superintendents with advanced degrees from university Departments of Educational or Administration began to become more common and a stable hierarchy of school management began to develop. As enrollments increased and the management of school systems became more complex, local board members gladly turned over more responsibility to city superintendents and their support staff (including those responsible for the maintenance of school properties, the implementation of health initiatives, and the organization of library resources). But while both school administration and teacher training had now become the realm of experts, those experts were far from agreed as to the nature of the "one best" system for American schools (Cubberley, 1916).

Section Three:

Early educational debates (Dewey vs. Thorndike and Cubberley)

Educational debates between 1900-1920s focused on the cultural theories of assimilation, pluralism, and religious or racial separation. The ongoing tensions between the need to: (1) maintain some semblance of Democratic ideology during a time of legalized curtailment of constitutional rights; and (2) assure a constant semi-skilled labor pool during a period of economic expansion, are reflected in the two predominant philosophies of education proposed by John Dewey (1899, 1910, 1916) and William Kilpatrick (1914, 1925) on the one hand; and E.L. Thorndike (1903, 1906, 1912, 1914) and E.P. Cubberley (1909, 1912, 1916, 1919, 1923) on the other hand.

In his early years, John Dewey (1859-1952) was precisely the kind of middle class scholar the New England public school system was designed to produce.[29] In 1882, having failed to receive a scholarship to the newly established Johns Hopkins University (a research facility set up on funds donated by a successful Baltimore business man), Dewey simply borrowed $500, enrolled, and studied under such major figures as G. Stanley Hall, Charles S. Pierce, and George Sylvester Morris. After receiving his doctorate in 1884, Dewey obtained a position teaching philosophy at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He was then hired both at the urging of Morris (who had transferred to Michigan to build a program in philosophy) and at least partially as the result of his mother's connections with the incumbent university president.

Beginning in 1871, the University had started admitting graduates of any secondary school whose program was approved by the university. Faculty committees were now routinely sent out to determine the quality of various schools and Dewey served on some of those committees. He became convinced that the quality of secondary schooling was ultimately dependent upon the kind of instruction students had received in the earlier grades. Many of the Michigan schools lacked coordination between programs, contained poorly conceived curricula, and exhibited a limited understanding of the methods of teaching. By combining these early interests in philosophy, psychology, and social reform, Dewey would become a uniquely pragmatic philosopher, one who used empirical and historical analysis as a "pragmatic" test of not only traditional metaphysics but also of teaching methods and successive proposals for democratic social reform.

In 1894, Dewey accepted an offer to head the combined departments of philosophy, psychology, and pedagogy at the University of Chicago on the stipulation that he would be able to set up a "laboratory school" for educational experimentation (Mayhew & Edwards, 1936). This facility, which came to be known as the "Dewey School," was not a practice school for the training teachers. It was an educational laboratory which served to exhibit, test, verify, criticize, and improve upon various pedagogical theories. Dewey's initial efforts received further notoriety, however, when Francis Parker's teacher training school became part of the university and was eventually consolidated with the undergraduate program in education to form a School of Education with Dewey as the head. Graduate work in education, however, continued to be done in the academic Department of Philosophy, still led by Dewey.

Parker's metaphysically based child-centered approach to education was primarily Froebelian (i.e., individualist). It assumed a latent directionality of each child's nature toward a "good social cohesion" given the proper opportunity for individual expression. Dewey's approach, however, was closer to a muted form of cultural-epochs theory. The more mental Darwinist adherents to that theory (such as Hall) assumed that class instruction had to be carefully matched with the period of past human development that corresponded to the child's current age. Dewey's more transformative approach, however, assumed only that proper education was a matter of helping a child rediscover significant lessons of past history through active engagement in representative experiences. Thus, at the laboratory school, children focused on various occupations of humankind in the pre industrial period: making cloth from fleeces (weaving, spinning, and dying); casting lead; weaving Indian baskets; and producing candles and soap (see Dewey, 1902; McMurray, 1946).

During the 1890s, Herbartianism was dominant in the training given in Normal schools; so-called because they set the norms or standards of education (Butts, 1955). Dewey agreed with the Herbartian list of five pedagogical steps (i.e., recall of prior experiences; presentation of new material; comparison and contrast to build relationships between old an new material; aid with drawing generalizations; and practical examples to emphasize the generalizations), but he was not a pure Herbartian.[30]

After an argument in 1904 with the university president over Dewey's wife's involvement in the running of the laboratory school, Dewey moved to the Columbia University but the school initially continued in his tradition. Dewey's two major educational works School and Society (1899) and Democracy and Education (1916) demonstrate his ongoing attempt to combine both educational experimentation and democratic ideals quite well. Both argued for a radical shift toward a truly progressive common school system where students would be expected to learn the common culture (i.e., the English language, American history, and the political system) but also where ethnic diversity was not only tolerated but encouraged.

To support his call for a shift in the pedagogical practices of common schools, Dewey pointed out that contemporary schools did not educate immigrant and poor children effectively by emphasizing rote memory and irrelevant learning's. Instead, they had produced armies of truants, delinquents, and criminals. His alternative (activity based) pedagogical approach suggested that carpentry, cooking, sewing, and weaving should be used to introduce students to the science and geography underlying the various forms of everyday socio-economic activity.

The main task for the child was to learn the various modes of historical development in food gathering, shelter, clothing; and this was done by actually experiencing the varied industrial or technological working roles associated with each mode of production. Textbooks were rarely used. Instead, Dewey attempted to make the school into a cooperative community by making occupations such as cooking, weaving, carpentry, sewing, and metalwork the basis for active learning experiences (see fig 18).

Figure 18 The Textile Room at the Dewey school (c. 1896). Breaking with the earlier traditions, Dewey argued that the teacher's duty was not just to impart theoretical knowledge but to induce a "vital, personal experience" in students that was somehow related to the ongoing conditions of daily life. As Dewey explained: "You can concentrate the history of all mankind into the evolution of flax, cotton and wool fibers into clothing." Reading, writing, arithmetic, and spelling were related to the activities undertaken by the students in the textile room (photo from Button & Provenzo, 1983).

At the Dewey school, individual attention was provided by using small numbers

of children and large numbers of teachers. An attempt was made to work out

a systematic curriculum for each child. This was necessary because a standardized

curriculum that depended upon impersonal textbooks and workbooks taught youngsters

to be overly subordinate and dependent on present societal authority rather than

helping them become active members in modern democracy.

Dewey's approach, however, was costly. It assumed that at least upper middle class funding would be made available for each pupil. This was simply out of step with the funding actualities of many districts across the nation. While consistently pragmatic, Dewey's approach was hardly practical. Dewey's primary focus on education waned when he moved to Columbia's philosophy department, which did not contain either psychology or pedagogy. Leadership in education then fell to his more conservative colleagues in education at Columbia's Teachers College and to other institutions such as Stanford University.

Thorndike: On the role of schools

In contrast with Dewey's calls for sweeping reforms, Edward Thorndike mobilized an administratively conservative and pseudoscientific rationale for his approach to education - an approach that eventually formed the basis for the mere adjustment of existing styles of American authoritarian schooling to the new physical conditions and sorting function of the expanding consolidated school system.[31] His Educational Psychology (1903) argued that since people differ in mental ability, schools had a duty to identify and nurture those differences:

"They help society...tremendously by providing it not with betterment, but with the knowledge of which men are good...The schools...always have and always will work to create a caste, to emphasize inequalities. Our care should be to emphasize inequalities, not of adventitious circumstances, but of intellect, energy, idealism and achievement" (1903, pp. 94-95).

For Thorndike, the newly developed standardized testing techniques would be the most equitable way of classifying or ranking these students according to their naturally given abilities. Consequently, he opposed the recent extension of compulsory attendance laws because they falsely raised the hopes of youngsters above their natural abilities and proper economic stations.

Cultural improvement from generation to generation he wrote, "depends on the elimination of the worse [from the educational system], not their reformation" (1903, p. 65). It was standardized testing that would carry out the culling function of the schools and these tests, Thorndike argued, would be based upon good old middle-class Protestant values. He expected that a properly run school system would allow immigrants to learn the English language and the customs of corporate America so far as they were able.[32]

Cubberley: On assimilation

A similar conservatively guided administrative reform approach was presented by E.P. Cubberley (1868-1941). He emphasized the case for educational assimilation of immigrants in a succession of textbooks written for the training of both teachers and public school administrators.[33] As Dean of Education at Stanford University, he took an active role in the shaping of teacher training and the writing of an historical rationale for continued administrative control over the nation's schools.

If immigrant children would only attend public schools rather than the denominational or foreign language parochial schools he suggested, they would begin to lay aside their Old World culture and pick up American ways. Schools were thus portrayed by Cubberley as the greatest agency for monolithically unifying the diverse elements of a culturally heterogeneous population. In particular, the virtues of the business ethos needed to be firmly implanted at an early age in order to fully prepare youth for the modern labor market. For Cubberley, compulsory schooling had as its essential goal the Americanization of the foreign-born (see Cremin, 1965; Newman, 1990).

Their respective influence on schooling

While Dewey proposed a shift toward a flexible, child-centered, and culturally relevant schooling system; Thorndike and Cubberley advocated a standardized, economic-oriented, and assimilative educational system. Despite the fundamental differences in their assumptions about the nature of human learning, the two approaches to teaching were usually combined ad hoc in most classrooms. This was particularly true in larger urban centers after the founding of the American Federation of Teachers (1916) -a teacher run union which differed considerably from either the administratively controlled NEA (founded 1857) or the ultra-right General Education Board (founded 1902 with Rockerfeller foundation funds).[34]

The cutthroat, administrative policies suggested by Thorndike and Cubberley, met successful resistance only after 1929 when Dewey's approach became reasserted in an operationized form suitable for the nation's depression era classrooms by William Kilpatrick, a Teachers College professor who had studied under Dewey.

Section Four:

Schools as Sorters (Prior to World War I)

This section outlines not only the traditional sorting functions of early 20th century schools, but also points out the openness of the modern public school system to the adoption of newly developed psychometric techniques. The differing motives for carrying out early individual intelligence testing are exemplified in the contradictory research goals of Alfred Binet (who developed of the first modern "intelligence" tests in 1905 and 1908) and Lewis Terman (who adapted Binet's tests and popularized their use in American schools). It will be argued that despite these differences in intent, the similar additive assumptions of both research programs have seriously undermined the utility of subsequent 20th century individual ability testing technologies as measures of typically human mentality.

Traditional and Modern Sorting Techniques

Before W.W.I, the primary means of selection in schools was simply one of the amount of funding available for each student. School budgets were set on the basis of local property taxes and vast differences existed between districts and between states. Since school districts themselves were formed de facto socioeconomic and racial boundaries, even students who managed to do well in inferior elementary schools would then be passed on to correspondingly inferior high schools.

With respect to the individual differences or special requirements of their student population, the administrative policy in poor or rural schools was simply sink or swim. Well funded districts with sizable populations, however, had long made specific allowances for administrative sorting of students into achievement and disability groups. As Chapman's Schools as Sorters (1988) points out, there were a panoply of such sorting plans in place prior to 1912. A survey (Van Sickle et. al, 1911) sent out to over 1200 superintendents of school systems in cities with a population greater than 10,000 people found that: 10 percent of the schools provided special classes for the physically exceptional (blind, deaf, dumb, and crippled, speech defects), and 17 percent provided classes for the morally exceptional (delinquents).

The widest use of special classes, however, was for: (1) the environmentally exceptional (non-English-speaking immigrants and late-entering students), 39 percent; and (2) the mentally exceptional (defective, backward, and gifted), 42 percent (see also McDonald, 1915, In Chapman, 1988). In effect, school administrators were now routinely placing immigrant, Black, and poor children into low-ability classes and into substandard or moderately adequate vocational programs.

At first, the stratification of high school programs was advocated because it seemingly served the varied needs of a rapidly growing, stratified, industrial nation. The typical high school graduate of 1900 was an educated person, fluent in the English language, and knowledgeable about American history and Western European culture but the very requirements for success in modern existence were changing. While the growing communication industries (i.e., the newspaper, telephone, radio industries) certainly needed workers proficient in English, standard factory production now needed a supply of industrially educated workers to manage assembly lines, and the military required technologically skilled soldiers to man the ever more destructive weapons of war (see fig 19).

Figure 19 Transition from the "Old" to the "New" U.S. Navy. The upper panel shows that even with steam propulsion, the old navy depended upon the muscle of large portions of the crew -including marines- to perform many tasks. The introduction of oil-burning engines into the new battleships, destroyers, and submarines after 1904 freed their crews from the ordeal of coaling the ship. Like other innovations, however, the transition was slow. By W.W.I, most of the battleships and many of the destroyers were still fired by coal. The lower panel shows a typical Navy recruiting poster (1909). Notice the reference to "efficiency." Over one third of the men applying for enlistment were routinely rejected due to physical disability (photos from Harrod, 1978).

In 1906, the National Society for the Promotion of Industrial Education (N.S.P.I.E.) was organized and politically active at both the state and federal levels of government. Their efforts paid off with the enactment of the Smith-Hughes Act in 1917.[35] By 1918, under the dictums of the Modern School movement (supported by both the General Education Board and by the upcoming NEA Cardinal Principles report), vocational and mathematical courses were to be emphasized along with exposure to basic English grammar courses (Anderson, 1978; Langemann, 1983).

Although economic rationales were the predominant public arguments put forward for vocational training and tracking, there were other arguments too. In academic circles, student attrition rates and assignment to curricular tracks in public schooling were being rationalized in hereditarian terms from 1903 onwards. In other words, under the guidance of educated administrative reformers, the schools were now becoming the primary means by which the sorting out of 'deserving from the less deserving' citizens took place.

Not God but the "Germ plasm" was now viewed as manifesting itself in the accumulation of wealth. As mentioned in chapter 2, hereditarianism provided a major practical and intellectual context for both animal research and for the undergraduate training of psychology and education students. Outside academia, too, routine sterilization's and eugenics-guided court decisions were also in place.[36]

Psychometric Ability Testing Proposed by Terman

The public school tradition of student sorting provided the immediate biographical and institutional setting for Lewis M. Terman to promote and tentatively apply standardized tests in school settings. After all, Terman himself was a survivor of that traditional sorting system. As the twelfth of fourteen children from a rural Indiana background he attended a one-room school where the teacher allowed him work at his own accelerated pace. For an Indiana farm boy in 1890 the first step in obtaining a higher education was to prepare to teach school children himself. That way he might manage to earn enough money for college. Not to teach, of course, meant to continue plowing fields.[37]

Directly after receiving his PhD in Psychology from Clark University in 1905, Terman served as a high school principal in San Bernardino, California until 1906. When he was hired to teach "child study and pedagogy" at Los Angeles State Normal School (later part of UCLA), it became particularly clear to him that the nation's overcrowded schools needed a more efficient way of classifying students into ability groupings. In 1910 (with the direct help of Cubberley), Terman received an appointment in the fledgling Education department at Stanford and, between 1915 and 1925, he developed a variety of mental ability tests which became widely used in American education. These include the Stanford-Binet (1916); the National Intelligence Test (1920; 1923) for grades three through eight; the Terman Group Test (1920) for grades seven through twelve; and the Stanford Achievement Test (1923), a battery of tests designed to measure school accomplishment in various subject areas.

Conflicting Roles for Individual Testing (Binet vs. Terman)

Terman, diverged considerably on two counts from Alfred Binet's prior groundbreaking mental testing work (Binet & Simon 1905). A difference with regard to both the proper role of individual mental testing in schools and the proper interpretation of testing results can be noted. Terman's positions on these issues was much closer to the "cast promoting" role of schooling put forward in Thorndike's Educational Psychology (1903); and his views on the "hereditary" basis of intelligence were nearly identical to that of his fellow G. Stanley Hall student Henry Goddard (founder of the Vineland Training School for the "feebleminded," in 1906). Like Galton and Cattell, however, Terman also showed considerable interest in the upper end of the so-called intelligence continuum.

Terman on genius and stupidity

Prior to the publication of the first Binet-Simon test (1905), Terman gained some understanding of Binet's ongoing work from his fellow Clark University classmate E. B. Huey who had visited Binet during 1903 and 1904 (Thorndike & Lohman, 1990). Terman's dissertation (supervised by E.C. Sanford) attempted to use mental tests (of his own device) to distinguish 7 boys judged by their teachers to be unusually backward from 7 boys judged to be exceptionally bright:

"My subjects were specially selected as among the brightest or most stupid that could be found in the public schools within easy distance of Clark University, in the city of Worcester. Three ward principals, by the aid of their teachers, made out a list of about two dozen boys of the desired age, equally divided between the two groups" (Terman, 1906, p. 314).

After explicitly aligning himself with the wider mental Darwinist tradition by accepting the premise that "the key to an explanation of ...intellectual differences...lies ...in native differences of emotional reaction" (p. 313), Terman also distanced himself from the former "superficial tests of a large number of individuals" carried out by Galton, Cattell, and Spearman. Rather than such "quantitiative" analysis which "will not allow several different types of reaction," his study was aimed at providing a Binet-style "qualitative analysis of the processes involved" by using test items that "allow...widely different attempts at solution" (p. 313, original emphasis).

As Fancher (1985) points out, Terman's tests were more like Binet's than Galton's, Cattell's, or Spearman's in their emphasis on higher complex mental functioning instead of lower physiological measurements. The test items fell into eight categories: invention and creative imagination (manipulating objects and numbers imaginatively); logical problem-solving; mathematical ability; language mastery; interpretation of fables; Chess rule learning (a new game to all); memory; and motor skill. On average, the bright boys surpassed the dull boys in all of these tests except motor skill. However, despite the care in which the subjects had been selected, only in mathematics and chess learning were there nonoverlapping distributions; in all other tests, the highest scoring dull boys surpassed the lowest scoring bright boys on that test. Terman noted but did not yet recognize the significance of the fact that the "dull" group was on average almost a full year older than the "bright" group (see Fancher, pp. 136-137). Thus, he considered his own fledgling foray into testing somewhat of a flop even when it was published as Genius and Stupidity (1906).

The Binet-Simon Test (1905)

The same year as Terman's doctorate was completed, Alfred Binet and a Paris physician called Theodore Simon published a series of three articles in L'Annee Psychologie describing their ongoing work which was aimed at ameliorating the educational crisis caused by the recent enforcement of compulsory attendance laws (originally passed in 1881).[38] Binet viewed human intellect as a generalized reasoning ability, which belongs to the normal development of the higher mental processes rather than to an adventitious concatenation of innately provided lower abilities (e.g., visual acuity and rote memory, or emotional reactions) as was assumed by Galton, J. Mck. Cattell, and later by Terman.

Unlike Terman's genius and stupidity study, the tests used in Binet & Simon's (1905) battery were intentionally reflective of the general trend of human beings to learn more with age. The essence of Intelligence itself (in contrast to the test items used in any test thereof), was defined only loosely as good judgment, common sense, initiative, and the ability to adapt oneself to changing circumstances.

As DuBois (1970) points out, Binet & Simon were able to take advantage of previous unsystematic work by French physicians working with children in a variety of clinical settings. Hence, in building their test battery, they systematically applied two predominant criteria for inclusion of test items for the first time: (1) scores on each item should show an increase with age; and (2) students judged brighter by the teacher should also earn higher scores.

The initial battery was first given to 50 children of varying ages with normal academic performance (i.e., ten children at each of the following ages: 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11). It was then given to 45 other children judged to be subnormal to varying degrees by their teachers or already institutionalized at Salpetriere. The resulting battery consisted of 30 tests arranged in order of approximate difficulty.[39]

Binet's "Scaled" Tests (1908; 1911)

By 1908 there were sufficient refinements to both the composition and arrangement of the sub-tests to warrant a published test revision. It was in this 1908 Binet-Simon "scale" that the concept of mental level was first used. Beginning with age 3 and extended up to age 13, groups of sub-tests were now formally arranged into an expanded set of 58 subtests (in which only 14 of the original 30 remained unmodified).[40]

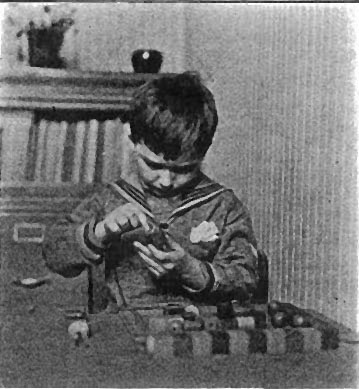

A child's mental level was now determined by the highest age at which he or she passed all (or all but one) of the tests, with an additional year credited for each five tests passed beyond that basal year. The change to include mental level expressed in terms of years, coupled with the greater range and organization of tests, increased the appeal of the scale outside France (see fig 20).

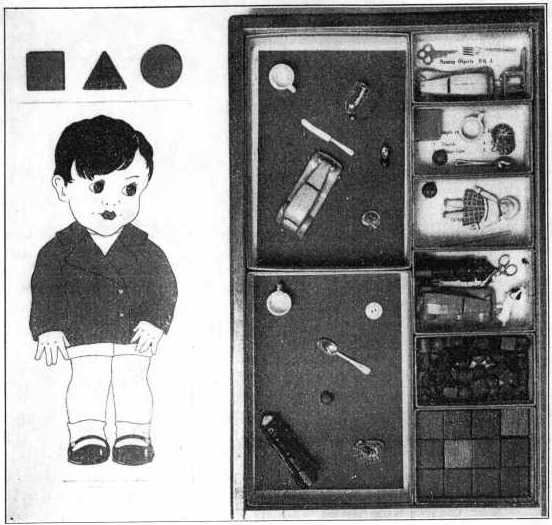

Figure 20 Individual ability testing. The upper panel shows Binet seemingly reflecting on the limited value of laboratory apparatus for yielding significant information about human intelligence. Reasoning and imagination (rather than rather than reaction time or sensory acuity) were now considered the essence of intellect. But the Americanization of the Binet tests (after 1908) brought with it a return to the hereditarian interpretations that had guided the older tradition (photo from Cunningham, 1997). The "standardization" of American testing procedures (after 1916) and the commercial production of test materials (after 1937) also had questionable effects on the comparability between Binet's original clinical style assessment (which required the examiner to draw together his own test materials) and the subsequent psychometric tradition. With successive American 'revisions,' the material details of even the purportedly retained subtests changed; sometimes in ever-so-subtle ways. For instance, the bead-stringing task (lower panel), part of the Binet-Simon tests (1905, 1908), was ostensibly retained in all subsequent American revisions. By 1986, however, the wooden beads had become plastic rings and the string had become a post (photo from Baldwin & Stecher, 1925; contrast with photo in Atkinson et. al., 1990).

Scores and labeling

As indicated above, three general classes of those at the bottom end of the "continuum of mental capacity" were recognized by Binet & Simon: Idiots (at the bottom of the scale); Imbeciles came next; and "Debiles"-which literally means "mentally weak" but which was translated as "moron" by Henry Goddard in 1916. Binet & Simon were careful, however, to emphasize that combined medical, pedagogical, and psychological methods were required for proper diagnosis of individual children. The results of testing, they argued have no value in themselves, they must be interpreted in light of this larger unit of analysis.

In a book written for popular consumption, Les idees modernes sur les enfants (1909), Binet commented specifically on the claims of others that intelligence might be considered both innate and immutable. "We must protest and react against this brutal pessimism" (Binet in Kamin, 1974, p. 5). It was here that he proposed a set of ameliorative "mental orthopedics" to help strengthen weak minds (see Fancher, 1985). Ideally, such mental exercises would be differentially applied to children of various experiential backgrounds in order to help them learn how to direct attention, manage memory, and employ sound judgment.

In 1911, Binet published a final revision of his test but it was already too late. The Americans had translated the 1908 scale and were now interpreting test results in hereditarian terms. When both Binet and Galton died in 1911, the arena for the measurement of mental ability shifted decidedly to North America. That is, it shifted toward the universalized sorting agenda of Thorndike, Yerkes, Goddard, and Terman.

Terman and the Stanford-Binet

Arriving at Stanford in 1910, Terman carried out a trial experimental study (using his own initial revision of the 1908 scale) on 400 schoolchildren near Stanford University. His report of the study (Terman, 1911) described the school only as "school x" but did provide a list of the tests he was using. He had added interpretation of fable tasks and sentence completion tasks to the basic Binet (1908) set. Most importantly, however, he drew three conclusions from this study: (1) the tests at the bottom of the Binet-Simon scale were too easy; (2) that the tests at the top were too hard; and (3) that further standardization of the test directions and administrative procedures were necessary if successive experimental results were to be comparable.

Mirroring the older mental discipline approach (i.e., the universality contained in the Committee of Ten Report,1893), Terman suggested that future testing procedures would ideally have each examiner or scorer treat every examinee or test result in the same cordial yet procedurally standardized manner with careful adherence to the questioning or scoring protocols (as yet to be developed). Terman's statistically modernized, though ostensibly "tentative," revision of the Binet (1908) test appeared in 1912 (Terman & Childs, 1912) the same year as his "Survey of mentally defective children in the schools of San Luis Obispo (Terman, 1912).

By 1912, Terman was openly arguing the typical administrative reformer line: that children with low test scores typically clog the educational machinery and consume a disproportionately large part of the regular teacher's energy. Ironically, as to why these student were so mentally backward, he provided both case studies and Binet test scores which for him (though in clear contradiction to Binet), "give an extremely accurate estimate of the innate intellectual ability" (Terman, 1912, pp. 133-135). Not surprisingly, his prescription to remedy the situation (like Goddard's) was segregation of the feebleminded into either separate manual institutions or into lower academic tracks within the same school.

The Stanford-Binet Revision

Terman's Stanford-Binet (1916) which utilized Binet's 1911 test for just over half its items was the result of a carefully administered psychometric team effort. Half a year was spent in training the examiners, another half year in testing examinees. As a first step in developing the new scale, data on individual tests given by various examiners were tabulated, including the per cent of examinees passing the test at each age. Next the Binet material and forty additional tests were prepared for tryout with 905 "normal" children ages 5 though 14, all within two months of their birthday. In addition, results of testing some 1400 adults were considered in making the revision. Also, to insure a high degree of uniformity in scoring, Terman hand scored all the tests himself (DuBois, 1970).

The resulting Stanford Binet scale (1916) included 90 items: 6 at each age level from three through ten, 8 at age twelve; 6 at "average adult;" 6 at "superior adult;" and 16 alternates to be used as substitutes when a regular test was "contradicted" for some reason (DuBois, 1970, pp.51-52). It was also procedurally standardized. That is, the proper use of the materials (still gathered, however, by the investigator) was made as explicit as possible, and the importance of gaining and maintaining "rapport" with the examinee was also highlighted. This was done so the test could purportedly be given under similar administrative conditions anywhere. The test booklet also included statistical norms (tables that showed typical performance on the each sub-test).

In this vein of comparability of results, Terman (1916) reasoned that the educational environment of two children living in the same country "under anything but exceptional conditions" probably is similar a great deal more than it differs. It must be noted, however, that the children Terman is referring to here are decidedly Anglo-American. In establishing the statistical norms for the Stanford Binet, for instance, care was taken to avoid racial differences. None of the sample children use to set up the test norms was "foreign-born" and only a few were other than Western European descent.

Thus, even at this early stage of research, the American Binet norms were intended for a fictitious group of statistically homogeneous and culturally identical children of Anglo-American decent. This hardly allowed the qualitative description of individual mentality that Terman had been so careful to favor a decade earlier.

The

lack of correspondence between the modern realities of American educational

demographics (from 1916 onward) and the tidy regularities of mathematics

of his new test technique may help explain why there is a complete lack of pictorial

content in Terman's work. His approach to intelligence albeit statistically

tidy was also ahistorical. Subsequent introductory textbook writers

and scientific historians have been forced to refer to parallel or later developments

in order to reconstruct the rough material details of early intelligenceresearch

(see fig 21).

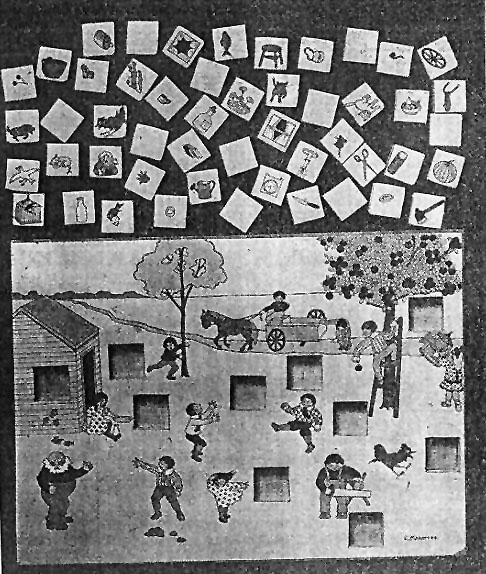

Figure 21 Early Individual "Performance" scales. The left and right panels show the Picture Completion puzzle, part of the Pintner & Paterson's clinical style performance scale (1917), intended as a "supplemental" test to the 1908 Binet battery (which they criticized as unwarrantably favorable to the verbal aspects of individual intelligence). Subsequent Binet-style tests (including Terman's) were also vulnerable to this criticism. At this early stage of empirical pot-shots, however, such differences in emphasis were to be expected. Binet's 1908 test, which utilized the notions of mental level and mental scale, proved to be a watershed for American psychometric "methodolatry" (Bakan, 1967) in the sense that adherence to empirical rigor was thereafter stressed (and even favored) over particular statements about exactly "what" was being measured (photos from Pintner & Paterson, 1923; Baldwin & Stecher, 1925; see also Pintner, 1929).

Exactly what Terman's test materials looked like we may never know but one thing is sure. This was rough and ready science, the mere starting point of the megalithic standardized test industry that would follow. A little later, Pintner & Paterson (1923) admit the immaturity of the subdiscipline by noting that in the recent "establishment of innumerable clinics" for testing, "theoretical considerations have lagged behind the practical application of mental tests" (1923, p.1). The early empirical forays, as a whole, however, are portrayed by them as "leading slowly to a... knowledge of what can... be called general intelligence" (p. 2). Despite their optimism, it is now clear to most historical reviewers that any generalizations about human intelligence arising from this early phase of initial empirical abstraction were bound to be equally abstract (see Ballantyne, 1995).

Stanford-Binet Norms and Revisions

Although Terman may have avoided showing us the rudimentary materials he used, he certainly did provide ample information about the mathematical trappings of his investigation. During the development of the 1916 scale, a pretest for proposed items was given to 310 California public school students (1910-1912) and this was followed by the application of a refined scale administered to 982 American born school children. That analysis yielding adequate results for ages up to 14, but the children in school above that age were by definition non-representative of their age group. In order to adjust the sample for this fact, and in order to further extend the age range to age 16, a wider group of 32 high school students, 32 owners of small business, 150 migratory unemployed workers, and 15 juvenile delinquents were included as part of the upper end of the Stanford Binet norms.

Setting the assumed mental age of the "average American born adult" at 16 presented no problem as long as test interpretation was restricted to refer only to the performance on academic school-like tasks under standardized testing conditions. But Terman did not subscribe to such a limitation on the generality of test results. Instead, he explicitly attempted to allow further generalization by way of emphasizing an new psychometric criteria for inclusion of test items.

Two of Terman's criteria for inclusion of test items were similar to Binet's: (1) each item should show an increasing passing rate with increase in chronological age; and (2) children judged bright by their teachers should pass the item more than those judged dull. A third criteria however was new: The items of the scale should be "internally consistent" (i.e., each item should be passed more frequently by those with higher overall scores). With this criterion, I believe, the rough clinically guided, pragmatic, and qualitative approach of Simon & Binet was replaced irrevocably by the still dominant American-style mathematical methodolatry of professional psychometrics.

The Stanford Binet test with its emphasis upon the internal consistency criterion is rendered a mere quantitative (and therefore by no means developmental) test of human intellect. That is, the very possibility of observing whether or not children with lower qualitative "levels" of mentality (e.g., Binet's Idiots, imbeciles, or debiles) might typically do some sorts of tasks better than children with higher levels of mentality (while at the same time obtaining a generally lower overall score) is literally excluded from the purview of psychometric investigation by virtue of Terman's third selection criterion. Thus, Terman's modernization of the Binet scales contradicted his own initial motive for favoring individual tests of higher mental processes: the investigation of qualitative differences in human mentality. All subsequent psychometric revisions of the Binet scale also statistically collapse quantity and quality in a similar manner (see fig 22).

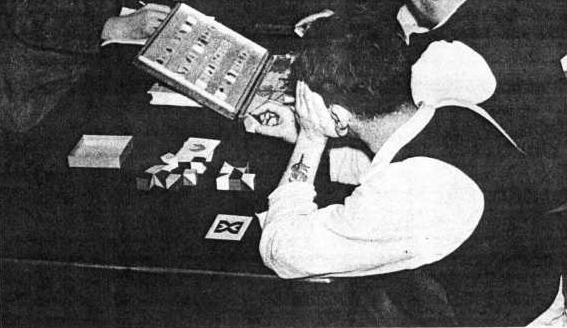

Figure 22 Stanford-Binet materials (1937) and Wechsler Test (1939). The upper panel shows shows the test materials for "Form M" for younger children from the Terman & Merril Stanford-Binet. This was the first Binet revision to provide a commercially available standardized set of test materials instead of having the investigator assemble their own materials. The designations for the two forms were "L" (for Lewis) and "M" for Maud Merrill; a long-term colleague and former student collaborator of Terman's. This test battery was standardized on a sample of more than 3 thousand American-born white children but was also translated into 20 languages within fifteen years (photo from Boring et al., 1948). The lower panel shows shows a penitentiary inmate taking the cube-pattern performance test; part of the "Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale" (1939) which was marketed as a corrective to the ongoing limitations of Binet revisions because it included both "performance" and "verbal" tasks. The caption accompanying this photograph suggests that the prisoner's competence in assembling the blocks, when considered in relation with other tests, "will help to reveal his mental age and his speical aptitudes, if any" (photo from Grabbe & Murphy, 1939).

In establishing the statistical norms for the early Stanford-Binet revisions (1916, 1937), Terman attempted to ensure the external validity of the test by including only American-born "White" subjects and by sampling from schools "average" socio-economic tax districts.[41] For Terman, however, the former control was more important than the latter because latent intelligence would typically express itself (as it had with himself) to some degree no matter what the quality or teaching emphasis of the school that child attended. Although this assumption contradicts both the Progressive era's tradition of debate regarding the "proper" pedagogic emphasis of public schools (i.e., child-centered vs. essentialist), and while it is also counter-historical in the sense that it downplays the importance of a major functional shift in the societal role of American schools (from their early concern with control or ethical conduct toward their later concern with academic or vocational training), it does not in fact contradict the primarily administrative rationales for the sorting of children in the modern early 20th century school system. Terman and his colleagues would soon take advantage of this fact to market standardized testing in schools.

The Additive Educational Ladder

Noting the similarity between the metaphorical "educational ladder" used by educational administrators and the eventual "additive hierarchy of mental ability" which followed from the assumptions of Terman and other psychometric testing enthusiasts is fairly important. For instance, it helps us understand how Terman might have turned away from his early emphasis on the qualitative relationships of human intelligence, and toward a quantitative empirical descriptor such as IQ (see fig 23).

Figure 23 The Additive Educational Ladder. The creation of consolidated school districts (see above) and of the later comprehensive high schools (see chapter 4) in the early part of the twentieth century, completed the establishment of a metaphorical "Education Ladder" used by Cubberley (1919) to describe the basic structural-administrative aspects modern education. The ladder ostensibly "served" pupils from their early childhood years through graduate and professional school. "All" children entered school at the lowest rung of the ladder, but only a few climbed all the way to the top. At each successive rung, some students left school and entered the world of work. While by 1920, most students entered high school, substantial numbers left for work during the high school years, and still more entered the working world directly after graduation. Even though college enrollments remained relatively small, and graduate school enrollment even smaller, the numbers of students emerging from the "highest rungs" of the ladder were always sufficiently large to fill the ranks of the growing middle and upper-middle professional classes (photo from Cubberley, 1947).

The earlier sections of this chapter have been provided in order to indicate that, if the modern American Public School system was formed to address the "needs of students" at all, the students under consideration were always middle and upper middle class White Protestants (or at least those willing or able to be schooled as such). Beyond that, the administrative details of modern American schooling have always been dictated by the changing requirements of its primary clientele: an increasingly industrialized capitalist economy. The guiding role of a specifically military industrial complex will also become more clear as the next few chapters unfold. Our main concern here, however, is to show why early American ability testing was part and partial to this pre-W.W.I additive administrative system.

More specifically, some of the biographical aspects of Terman's early career are relevant in understanding the ahistorical aspects of his later mental testing efforts. First of all, Terman was initially hired in 1910 by Cubberley as an expert on the physical aspects of child development in relation to schooling. This rather historically grounded topic was his main concern between then and 1915. In this vein, Terman both lectured on mental hygiene in the Stanford education department and also produced a string of articles for popular magazines including: Harper's Weekly, Popular Science Monthly, The Youth's Companion, The New England Magazine, and Forum (see Seagoe, 1975, p. 60).

Two textbook treatments were also produced: Health Work in the Schools (1914a) in collaboration with E.B. Hoag, a physician; and The Hygiene of the School Child (1914b) a text for teacher candidates in normal schools (revised 1929). Physiological maturity, posture, malnutrition, tuberculosis, dental hygiene, disorders of the nose and throat, problems of the ear and hearing, visual disorders, proper "ventilation," and "preventative mental hygiene" were all covered. Even the health of the teacher was made a topic of consideration.