Chapter 5

From New Deal Training Programs to World War II Testing:

Ideological maintenance, test standards, college entrance, and

predictive validity (1933-1946).

Paul F. Ballantyne

This chapter covers the training programs and testing technologies used in America during the Great Depression and World War II. As we are often reminded by psychology textbooks, improved statistical techniques developed during the depression provided a reliable means of sorting war industry workers and soldiers according to pressing and variable military need. What we are not often told, however, is exactly how the ongoing conservative assumptions and motives of the testing tradition diverged considerably from the progressive "New Deal" (and wartime) context of societal change in America. By highlighting the guidance and universality aspects of Federal New Deal Youth Programs (including their topical extension during wartime) and by contrasting them with contemporary refinements to the educational and vocational ability testing subdisciplines (including their widespread administrative extension during W.W.II), it is hoped that the selection and segregationist emphasis of the latter will become clear.

Chapter Overview

In section one, the economic and political context of the Great Depression (1929-1942), including its disastrous effects on public educational funding and the more positive emergence of the New Deal in the series of so-called alphabetic economic relief agencies (such as NRA, FERA, the CCC, and NYA) are covered. As the traditionally limited role of federal involvement in domestic economic affairs, ideological guidance, and educational funding was successively expanded the older economic impetus for psychometric sorting (entrenched into educational policy during the 1920s) receded into the background. While psychometric streaming of students continued in the ailing middle-class public school system, it received virtually no application in the historically important New Deal adult or youth programs (which emphasized civic works projects and applied vocational training) for the working class. Similarly, one high profile educational experiment also made a point of skirting the statistically centered tradition of standardized college entrance examinations. In this Eight-Year Study, standardized college entrance exams for selected schools were waived between 1933-1941.

Section two begins by outlining how the psychometric subdiscipline weathered the depression era market share slump for testing. The survival techniques initially involved both an active search for improved standards of test reliability, but also involved increased emphasis on promoting management biased vocational opinion polls, worker "attitude" assessment, and "social relations" training. Finally, the unprecedented W.W.II investment in testing technologies (for the "classification" of American inductees; the production of "qualifying exams;" and the "assessment" of specialized military training) is covered. This applied context of cooperation between the military, the APA, and the AAAP, provided a fair testing ground for the predictive validity of so-called general intelligence measures (such as the AGCT) and of more specific training or assessment devices used to select suitable candidates for specialized training (including pilot, bombardier, and Navy gunner selection).

The failure of the former "general" tests sparked a brief academic reevaluation of an older ontological issue (i.e., the relationship between an individual's generalizable academic intelligence vs. their more specific vocational knowledge). Ironically, however, by the end of the war, when the future educational prospects of American G.I.s and of national ethnic groups (especially "Negro" Americans) were under open debate in the halls of government, the fundamentally conservative psychometric subdiscipline was no closer to resolution on this issue then it had been 50 years earlier. The subdisciplinary emphasis had shifted back toward the safer empirical methods issue of predictive validity. This shift went hand in hand with an active promotion of vocational and intellectual testing measures as purely administrative devices for the post-war marketplace. Only after this marketability agenda was well established did there appear any passing acknowledgments that the "modern" conceptual and empirical adjustments of the psychometric tradition (including theoretical interactionism and operational definition) might be woefully inadequate for providing anything more than a descriptive analysis of the distribution or development of intellectual functions in human beings.

Section One:

The Great Depression:

Educational Funding, New Deal Programs, and Ideological Maintenance

Throughout the Great Depression, the public schools and the federal government were in conflict regarding the proper means to avoid wasting a generation of youth potential. Their argument with each other was over how to best structure the social and societal context of American youths (aged 15-18) in order to promote the normal production of physical, mental, and civic competence. The ability testing tradition, as a third subdiscipline concerned with such questions predated this modern debate over the allocation of cultural/mental infrastructure.

The older tradition tended to reify the pre-existence of social and societal competencies (to a greater or lesser degree) as if they were simply allowed to "develop" (mature) within the broader realities of a cultural context. Thus, while the New Deal form of discourse tended to be transformative, the ability testing tradition tended to be merely additive or adjustive. The contrast with the public school discipline, on the other hand, was less striking. For various reasons, the public schools kept one foot in both of these camps. It did recognize, however, that the older meritocratic ideals of the ability testing approach to educational efficiency was inappropriate given the conditions of complete economic calamity.

Being hit hard by the depression meant that school administrators turned their attention away from "educational progress" of the 1920s and toward the pragmatic maintenance of a basic curriculum, of staff, and building facilities. Educational associations resented the federal government's expenditures on the New Deal youth programs (such as the CCC and NYA) and even resented the educational components of adult aid agencies (such as NRA, PWA, and WPA). Both types of program were blamed for drawing funds and youths away from the ailing public school system. Roosevelt's New Deal government, on the other hand, argued that "curricular entrenchment" (i.e., lack of vocational relevance of classroom work) had already caused droves of students to leave the public school system for the breadline. Federal programs which would address both the physical needs of youth and the wider ideological requirements of liberal democracy were now under consideration. Their goal would be to promote youth employment and forestall youth involvement in crime or extremist politics (Reiman, 1992).

The ideological installment of democratic values and public image management of federal civil authority was made an important undercurrent for both the "war on the depression" (Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Youth Administration programs) and the FBI's war on crime. Similarly, the successful, progressive educational institutions were now lobbying for a trial of their alternative curriculums in the context of higher educational institutions. Thus an "eight-year study" on collegiate entrance was held between 1933-1941. While these apparently transformative movements were underway, however, the pressing needs of national security resulting from the start of W.W.II were redirecting the emphasis of federal youth programs and or public school education toward defense readiness.

Public school funding after the crash

Historians typically date the start of the Great Depression to Black Tuesday, October 1929, when a long period of unrestrained corporate greed (dating back to the 1890s) precipitated a national stock market crash (Wecter, 1948; Shannon, 1960; Bird, 1966; Chandler, 1970; Duboff, 1989). Farmers and more rural cities, however, had been feeling the fiscal crunch throughout the 1920s as the European demand for American agricultural produce steadily decreased (Silverman, 1982). Indeed, although there was a growth in the number of middle-class Americans between 1922-1928, working people generally missed out on the "roaring twenties" (Bernstein, 1960; Shover, 1965). For instance, between 1920 and 1929, the income of the bottom 93 percent of the population rose only 6 percent, while that of the top 7 percent increased almost 200 percent (Rose, 1994; see also Leuchtenburg, 1958). Foreign demand for manufactured goods in turn began to slump and by the time of the big crash, two of every three American families was already poor (Hill, 1990).

Conversely, the consequences of the crash were felt only gradually by the middle-class biased public school system. The initial tendency, therefore, was to downplay the relevance of the wider economic crisis to the public school system (Rippa, 1962; Mirel, 1984). Like the incumbent Republican President Herbert Hoover, most school administrators by definition had bought into the ongoing business ethos of efficiency.[75] They initially believed that the economic prosperity of the 1920s would soon reappear and that financial support for education would remain relatively stable throughout the crisis (see Callahan, 1961). Most city school systems, for instance, received slightly larger budgets in 1931-32 school year than they had in 1930-31. In fact, however, since the depression had now crushed real estate values, it would soon crush public education.

By the 1932-33 school year, with several large cities on the verge of bankruptcy, the possibility of hard times ahead was becoming more clear. The National Survey of School Finance, authorized by Congress in 1931, reported early in 1933 that half of the states obtained 90% or more (and five sixths of them 80%) of their fiscal support from locally collected general property taxes (Knight, 1951; Tyack, et al., 1984).[76]

Within the immediate context of administrative control of the schools, detailed cost accounting was demanded of each district and each so-called frill program. Night schools, summer schools, kindergartens, and playground maintenance, music and nonacademic subjects (such as music, art, physical education, industrial education and special classes for physically or mentality handicapped) were cut entirely or severely scaled back. Teachers salaries which comprised 75% of the budget were also cut and teacher layoffs became commonplace after 1933. Some teachers were paid in "tax warrants," School Board IOUs, which many stores refused to accept and other accepted only at a discount (Urban & Wagoner, 1996; Button & Provenso, 1983).[77]

By now, the era of blind compliance with local school supervisors had passed. Membership in teachers organizations (such as the American Federation of Teachers and the Progressive Educational Association) which had fallen victim to the anti-unionism of the 1920s began to climb steadily. In 1933, even the administratively controlled NEA was stirred to action. It formed the "Joint Commission on the Emergency in Education" which eventually suggested two major ways to solve the financial problems of local schools. One was the pursuit of direct federal aid for education, and the other was state tax reform.

While neither of these efforts was completely successful (see Wesley, 1957), the data gathered through successive NEA surveys allowed local school districts to compare their own fiscal circumstances with that of other similar districts for the first time. It became increasingly evident that more consistent state taxation and federal aid was needed to counterbalance the vast regional educational inequalities produced by the long-standing fiscal dependence upon local property taxes (see fig 38).

Figure 38 NEA School Survey. The above panel appeared in the America School Board Journal (1934). The Romanesque style woman represents public education, far above the din of industry and everyday life. She is reading the report of the NEA experts on how to improve the schools. The cartoon also hints at the post-stock market crash elevation of education (and teachers) relative to businessmen. The pervasive feeling that local business interests had betrayed the public schools was expressed in education journals from 1932 onward (e.g., Cubberley, 1933) and was quite a change of tune for a profession that had consistently celebrated progressive aspects of free enterprise during the 1920s. The rapid reverse of opinion struck some observers as skin-deep (see Counts, 1932; Newlon, 1934, 1939; Bowers, 1969). Most educators were sincerely distressed by the suffering they saw and angered by cuts in school budgets, but very few were yet radicalized. By 1934, the public education establishment would also claim that they had been abandoned by the lower-class biased New Deal educational initiatives which ran largely parallel to the traditional public school system. The schools, however, did benefit significantly through the mechanism of federally mandated public works projects on school buildings and grounds (photo from Tyack et al, 1984).

The Old Deal defines the "New Deal"

Along with the new Democratic President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, came a new approach to tackling the economic crisis. Roosevelt had defeated Hoover in the 1932 presidential election but it was another year before the first part of the National Survey data was available. In that time, the ostensibly self-correcting free market economy of Hooverism showed no signs of recovery. When Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933, nearly 13,000,000 persons, or 25 percent of the nation's workforce were already unemployed and banks had been closed in thirty-eight states (Bernstein, 1970). Roosevelt soon put into place a successively more radical policy of direct federal economic intervention appropriately called the "New Deal" (see Bernstein, 1985).[78]

Early New Deal Reforms

At first, the economic and political realities of the old deal set the limitations for the New Deal (Howard, 1943; Hawley, 1966). Between 1933 and much of 1934, the new administration had to contend with a sizable portion of American society that wanted to continue to employ the existing public institutions (such as public schools and existing governmental agencies) to remedy the ailing economy. Business interests (and those advocating further educational entrenchment) were still powerful and criminal corruption of the judicial system was combined with intimidation in the industrial workplace as the established order of the day (Bernstein, 1960). The early programs under the National Recovery Administration (NRA) were, therefore, quintessentially conservative. They were aimed at rescuing or reforming the old economy rather than transforming its structural underpinnings (Schwartz, 1982; Susman, 1983).

Walking the political tightrope between rising unionism and those of ailing big business, the New Deal administration portrayed their early economic measures in politically centralist terms as: (1) helping business be more safe for American tax payers; and (2) stimulating economic recovery by promoting cooperation between government, business, and labor (Baritz, 1960). For example, only after shoring up public confidence in the banking system with the federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and only after similarly stabilizing ongoing agricultural overproduction through farmer subsidies (but also via forced removals of tenant farmers) under the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), were the more novel (left leaning) series of "civil works" projects brought into place.

Similarly, the Public Works Administration (PWA), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the youth oriented programs -including the Civil Conservation Corps (CCC) and National Youth Administration (NYA) programs- were all initially portrayed as "relief" oriented programs aimed primarily at putting the nation's unemployed to work on politically defensible civic improvement projects (see Williams, 1939; Brown, 1940). The agencies were functionally conservative in their aim to remedy the ailing economy without disturbing the predominant middle-class values of the American industrial society (Schwartz, 1982). Likewise, the educational aspects of these "alphabet agencies" were consistently aimed at providing young lower-class White men (and a small percentage of Negro youths) with a basic level of vocational marketability that would be immediately useful in a post-depression economy.

Constant deference was shown to business interests throughout the early New Deal era. Successive repeals of minimum wage-rate policies; severe curtailment of "production-for-use" projects, and the abrupt cessation of the innovative Civil Works Administration (an attempted compromise between a relief and an "employment" program), were all enacted on the basis of their unfair competition with the private sector. Also, virtually all New Deal programs (even the federally sponsored migratory worker camps or "transient" camps) were de facto segregated with consistently lower pay and facilities being provided for Negroes (Salmond, 1965, 1967; Schwartz, 1982; Rose, 1994).[79]

Even these relief programs, however, necessarily entailed sponsoring educational and training initiatives designed to allow unemployed and dispossessed workers to return to the regular workforce. The educational aspects of WPA, FERA, and the youth programs were not common schooling aimed at all segments of the population. They were specifically designed for the poor and staffed largely by people already on relief (Tyack, et al, 1984). This was a new style of education premised on the notion that all kinds of people can teach and that learning can take place in various settings. Public schools did, however, receive federal aid in the form of maintenance and school construction work done by WPA members so the New Deal programs were designed to supplement rather than supplanted the standard public school system.

In the novel aspects of early New Deal planning policies, however, the seeds were sown for the later more progressive reforms. These were to come especially after the renewed recession of 1938. Only then was it clear to most voters that continued bows to the ongoing business ethos would actually stand in the way of further economic recovery.[80] Hence, the "later" New Deal reforms (between 1935 and 1941) were brought into play with the expressed intention of protecting citizens from the outmoded hazards an uncontrolled free market system.

Further New Deal Reforms

The Social Security Act (1935) to provide old-age pensions, and the National Labor Relations Act (1935), introduced by Senator Robert Wagner (a New York Democrat) can be viewed as successive steps toward the left in the domestic affairs of the New Deal administration. The "Wagner Act" is particularly relevant here because it: (1) provided a mandate for the National Labor Relations Board to adjudicate management-labor disputes; (2) guaranteed labor's right to organize unions and engage in collective bargaining; and (3) outlawed specific unfair labor practices. One of the most controversial sections of the N.R.A. (1933) was 7a, which said that employees shall have the right to organize and bargain collectively and shall be free form the interference, restraint, or coercion of employers.

Roosevelt had initially hesitated in supporting labor unions. The Wagner Act provided a clear message to large employers that unions were part of the solution to the nation's economic woes and not part of the problem (Bernstein, 1970, 1985). The Act also allowed so-called group relations to assume an importance of the first order. This created a market for the labor relations technology of sociologists and industrial psychologists. Employers could no longer treat employees on an individual basis but had to work out formalized company policies. Personnel selection, training, or advancement, were once considered the private prerogative of employers. They were now to becoming part of an institutionalized pattern of the workplace (Fairchild, 1937).

Image management and the FBI

Another important aspect of federal intervention, in 1935, was the formation of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The new FBI was actually an amalgamation of three pre-existing agencies: the Prohibition Bureau (which had been transferred to the Justice Department in 1930), the Bureau of Identification (with its massive card file fingerprint repository under J. Edgar Hoover), and the Bureau of Investigation (also under the control of Hoover). The formation of the new FBI was politically orchestrated by the Homer Cummings (the incumbent Attorney General) but was soon under the de facto control of its appointed director Hoover.

Upon taking office, the Roosevelt Administration's original plan was to scuttle both the existing Prohibition Bureau (due to the proposed repeal of prohibition) and the Bureau of Investigation (as a cost cutting measure).[81] Within the Department of Justice, however, the new Attorney General (Homer Cummings) was astute enough to recognize that considerable political mileage could be gained from promoting the formation of an expanded, re-equipped, federal policing force as a solution to the ongoing lack of public faith in local and state law enforcement.[82] In 1933, Cummings portrayed the Kansas City Massacre, in which four lawmen (including one bureau agent) and their handcuffed prisoner (Frank Nash) were shot down while stepping off a public train, as a direct challenge to the federal government's anti-crime crusade. He then skillfully utilized public uproar over a jailbreak by another Midwest gangster, John Dillinger, to speed a series of crime bills (including the power to ware guns and to offer rewards) through Congress during the spring and summer of 1934 (Powers, 1983; Breuer, 1995).

So, as the National Recovery Administration was sanctioning various "relief" programs such as the AAA and CCC for their "war" against the depression, the newly endowed federal Justice Department was initiating a country wide war against the notorious public enemies such as Dutch Schultz, Al Capone, and John Dillinger. It was intended that the Attorney General would remain as the functional human link between the public's crusade against crime and the New Deal's political program of national unity. But this was not to be the case because in forming the new FBI, the administration had necessarily relied heavily upon the prior decade of G-man image-building orchestrated by the director J. Edgar Hoover (in his former capacity as head of the Bureau of Investigation).[83]

This interplay between political versus bureau control, and the related concerns over public image management were also being played out in the substance, form, and goals of other New Deal programs (including the youth-oriented CCC and NYA). Another impetus of change in the mandate of such domestic programs, however, was the still wider arena of foreign policy. From 1936, onward, Roosevelt and his administration had been moving cautiously to break down long-standing American isolationism on the grounds of national (and international) security (Jonas, 1966; W. Cole, 1983).[84] This national defense theme was especially cogent to the CCC military "preparedness" initiatives after 1939 and to the slightly earlier "ideological maintenance" initiatives put in place in so-called NYA resident camps (Reiman, 1992). We will take up each of these programs in due course.

College Entrance and Progressive Public Education

Given their perpetual endowments, the better established higher educational institutions did not have a clear incentive to transform their programs. Despite the hard economic times, and despite the successively more radical New Deal Youth programs (as described in detail below), the higher educational system continued the conservative structural reforms began in the late 1920s. American universities, in particular, continued in their material growth throughout the whole period between the world wars and were an attractive refuge for out of work white-collar workers (Touraine, 1974). Many institutions did, however, attempt to adjust their entrance requirements in accordance with pre-depression administratively motivated "progressive" trends. This was particularly true of high school and college level institutions which were thereby able to continue a rise in attendance at the pre-depression rates (Tyack, et al., 1984, pp. 144-150; USBC, 1975, Vol. I, pp. 368-374).

The SAT and GRE

One indication of how this conservatism expressed itself in tough times is the continued expansion of use of objectified standard entrance exams for higher education (Cheydleur, 1937). From 1926 to 1935 the number of candidates taking the older essay style written exams each year declined from over 22,000 to fewer than 14,000 but in the same period the number who took the objectively formatted SAT increased from 8,040 to 9,437. Moreover, 3,000 SAT examinees in 1935 did not take any of the Board's written exams because some colleges were now requiring only the SAT (Valentine, 1987; Owen, 1985).

The older program of written exams was on a downhill slide partly because it was now recognized that examination costs could be "cut in half by the use of objective tests" (Brigham, 1934 In Valentine, 1987, p. 40). After the introduction of the Graduate Record Examination in 1936 it was used experimentally by the College Board to augment essay-based college admission tests to some graduate schools prior to W.W.II. There was also considerable talk about merging the various competing business factions in the objective testing industry (Lagemmann, 1983). These included: the College Board, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; the American Council on Education, and Woods' Cooperative Test Service.

Ben D. Wood was hired by the College Entrance Board to run trial applications of the Graduate Record Examinations (GRE) which originated in 1936 under Carnegie Foundation funding and under the direction of Wood's Cooperative Test Service. The GRE is essentially an upward extension of the SAT (i.e., a higher level of difficulty for each question). Despite later claims to the contrary, the successive introduction of the SAT and GRE as official college entrance requirements functioned to deter those without appropriately conservative (elitist) high school and college experience. They were put in place to increase the reliability of selection of students and hence to maintain the societal stratification of those institutions (a.k.a. the "status quo"). Standardized testing requirements were certainly not intended to be (as later claimed) creators of opportunity or equality of access to higher education (Owen, 1985).

The Eight-Year Study (1933-1941)

In distinction to these conservative trends, one indication of the partial continuance of child-centered progressivism was the Eight-Year Study. During the early 1930s, when lower ranked colleges were hurting for students, they became more receptive to ongoing complaints from progressive educators about how colleges requirements were dominating the high school curriculum. Conceived initially as a response to the problems of college admission, the Eight-Year study also became a landmark in the movement to update the secondary school curriculum toward so-called Life-Adjustment Education. That is, to broaden the typical public school experience to address the needs of the 60% of students who were neither planning to enter university nor go directly to work after high school (Spring, 1988).

In 1933, over 200 colleges and universities agreed to waive the standard entrance requirements for students from 30 selected progressive high schools on an experimental basis. Of the large Eastern colleges only the ultra-exclusive institutions of Harvard, Radcliffe, and Yale refused to participate (Aikin, 1942; Leigh, 1933; Zilversmit, 1993). Between 1933 and 1941, the selected schools were allowed to make whatever curricular changes they deemed in the best interest of their students. These schools, however, were hardly a representative cross-section of the American secondary education system. They had been selected by a Progressive Education Association committee in 1932 because they were already well known for their quality as "progressive" schools. Thirteen were private schools, six were laboratory schools connected with universities, and eleven were public high schools with innovative systems (Leigh, 1933).[85]

The dice was thus loaded in favor of the "success" and the study. It was also funded by an enormous grant from the Carnegie Corporation ($70,000) and the General Education Board ($622,500) and assisted by an evaluation team led by University of Chicago professor Ralph W. Tyler (Tyack, et al., 1984). The effectiveness of experimental curricula were judged in terms of how well their graduates did in college. Each graduate in the study was paired with a comparison college student from a high school not in the agreement. Not surprisingly, given the upper middle-class backgrounds of the students, the selected graduates did well in terms of both academic and nonacademic ventures. There was no significant overall difference in the scholastic outcome of the experimental school group from the comparison group accepted from conventional high schools (Krug, 1960; PEA, 1943).

However, among the 30 selected schools, there were considerable variations in the degree of curricular departure from conventional programs. Additional analysis by Chamberlin (et al., 1942) indicated that these differences actually favored the success of students from the most experimental schools:

"The graduates from the most experimental schools are characterized not only by consistently higher academic averages and more academic honors but also by a clear-cut superiority in the intellectual intangibles of curiosity and drive, willingness and ability to think logically and objectively, and an active and vital interest in the world about them....The students from the least experimental schools are, on the other hand, seldom distinguishable [sic] from their matches" (pp. 173-174; Quoted in Krug, 1960).

For Max McConn (1942), preface writer for the Chamberlin volume, the case against curricular essentialism (e.g., Bagley, 1938; Spaulding, 1938) seemed to be fairly well sown up. The Eight-Year study results were favorable to the more experimental curriculum:

"From now on if any individual dogmatically asserts that the traditional program is essential for college success, he can be politely assured that he is talking nonsense, ...and can be counseled to consult the evidence before conversing further on this topic" (pp. xxi-xxii; Quoted in Krug, 1960).

The results of the Eight-Year study, and their contemporary interpretation possessed the makings of an argument against the eventually universal application of college entrance exams (such as the SAT and GRE). To better understand why subsequent testing history unfolded the way it did, we must therefore look in more detail at the contrast between the New Deal Youth Programs (which emphasized guidance and universality) and the ongoing psychometric testing tradition (which emphasized selection and segregation).

Youth-oriented New Deal programs:

Physical and Ideological Maintenance

For the vast majority of youth, the frivolous lifestyle of the 1920s youth culture ended abruptly when the economic depression struck. Unemployed and out of school youths now became a central issue. Like the other marginal groups -such as Black Americans- youths were the last hired and the first fired from the depression era workplace (Spring, 1994).[86]

The first federal emergency relief program for youths began in 1933 with the establishment of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). This program involved housing unemployed youth workers in camp settings run according to quasi-military discipline (Hollingsworth & Holmes, 1969). Initially, only youths between the ages 17-23, not presently attending school and with families on assistance were eligible but the latter criterion was later relaxed. Enlistees received housing, clothing, food, and a wage provision of one dollar per day. The minimum term of service was six months and the maximum two years. In 1934, modest funding for college and university student education through the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was put into place, and in June of 1935 this was extended to high school students when Roosevelt established by Executive order the National Youth Administration (NYA).

The CCC and NYA were both conservative relief ventures in that they followed (with different emphasis) the two ongoing themes of physical and ideological guidance for the promotion of democratic values. Richard Reiman (1992) has pointed out that the CCC reflected the older 1890s idea that youths require physical conditioning and group organizational structure to pass successfully toward adulthood. This was the same idea reflected in the Boy Scout movement in Britain 1908 (extended to the U.S in 1909) and in the Wodervogel movement in Germany in 1901. The criterion for success of the CCC program was predominantly one of physical and mental toughening (i.e., the transformation of scrawny enrollees into strong and healthy well-disciplined workers).

In contrast, the NYA was formed on assumptions that took into account that this was a novel historical age in which middle-class youths were routinely the intellectual equal of their parents at an early age. Thus the pure form of the physical doctrine (by which youths are placed in a natural setting to allow the "instinctual" seeds of adulthood to germinate) was rejected in favor a program that increasingly involved both: (1) physical and mental toughening; and (2) ideological maintenance of democratic values. This latter combined approach was more in line with the "muscular Christianity" of the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) and to a lesser extent with contemporary European youth movements (Macleod, 1983). Whereas the CCC stressed the value of conservation projects for the nation and of learning the discipline of work for working-class youth, the NYA embodied a concerted effort for the vocational adjustment and ideological maintenance of lower-to-middle-class youths.

Civilian Conservation Corps (public image, daily reality)

The public image of the CCC was carefully managed in the early days of the New Deal. "It was partly a legend built by and for a middle-class America that wanted to believe in itself again, to think that an era of exploitation was over, that now the society was conserving, not wasting, its resources and that worthy young men once again had a chance if they worked hard" (Tyack, et al., 1984; p. 117). But the actual enrollees were hardly Eagle Scouts. They tended to be irresponsible, unhealthy, unclean, and without what the middle class would call mental or moral stamina. About a third were from broken homes; most from rural backgrounds; and they had completed an average of eight or nine grades. Few of them had held any (let alone steady) previous employment positions.

As initially planned, these lower-class CCC youths were to learn the values of liberal democracy by carrying out useful civil works which would help support that democracy during a time of national crisis (Oxley, 1940). The construction projects included: parks, and campgrounds; dams and lakes; regenerated forests and farmland; wildlife refuges and wilderness areas; historic sites, lookout towers, trails, roads, and bridges. In addition, millions of acres of land were mapped and surveyed by CCC enrollees (see fig 39).

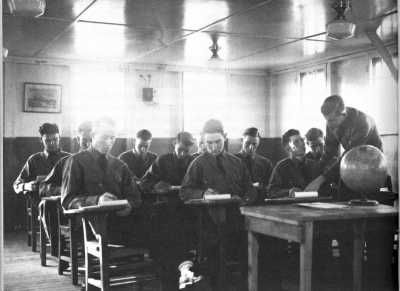

Figure 39 Education in the CCC work camps. Exposure to nature and to organized adult discipline was the order of the day for lower-class in CCC work camps. The authoritarian military officers and technical advisors from the U.S. Forest Service in charge of the camps, provided a regime of low-level (and fundamentally conservative) educational activities characterized by basic drill in literacy skills, a strong emphasis on discipline and the values of hard work, and lessons in "common courtesy." The first CCC camp was opened near Luray, Virginia, on April 17, 1933, followed by many other camps in various parts of the country. Through July 1937, this youth organization had constructed more than three million small and forty thousand large dams to prevent soil erosion; fought thousands of forest fires; and had planted millions of trees. Thus was carried out the "molding" of the character and bodies of 3,000,000 lower-class Americans. Most of the enlistees were youths, but 225,000 of them were W.W.I veterans, who (organized into their own companies), were given a chance to rebuild their lives in the camps. They played a major role in controlling the "Dust Bowl" of the nation's central region. In a massive effort to help stop soil erosion, the 3C's boys planted windbreaks, or shelter breaks strategically placed across the Great Plains from Canada to Mexico (see Hill, 1990; photo from Tyack, et al., 1984).

To speed up building and administration of the resident camps, the Army was put in charge with the Forest Service and the National Park Service helping to plan and implement the construction projects. The American Federation of Labor initially opposed the CCC in the spring of 1933 because it might conceivably provide a readily available force of militarized strike-breakers. In a bid to address these fears, Roosevelt appointed an official of the Machinists' Union, Robert Fechner, as the CCC Director (Gower, 1967).

Not only was the CCC to be an instrument for the conservation of natural resources, it was also to perform an education function (see Hill, 1935).[87] There were three major classifications of courses taught in CCC camps: (1) remedial classes (for those who were illiterate or had only rudimentary schooling); (2) vocational courses; and (3) liberal (non-vocational) instruction. The various groups in the camps differed as to which of these would be given relative merit over the others. It was routine for each camp educational adviser to recruit course directors from: available Forest service and Army officers; experienced corpsmen; as well as from local professionally trained public school teachers. These were courses specifically designed for the poor and staffed largely by people already on relief. They were neither based on the canons of professionalism nor designed by certified experts.

The Army took their traditional mental and physical discipline approach aimed at teaching the boys how to do an honest day's work (Sloper, 1940). Reveille at 6:00 A.M. was followed by physical training, barracks inspection, and hard work broken only by meals and recreation or training in the evening. One in five enrollees deserted or was dismissed from their camp; the actual average term of service was only about nine or ten months. Accordingly, some idealistic federal education officials and many of the national public school leaders argued that the CCC camps were too authoritarian and uninterested in educational activities that would promote subsequent participation in democratic society. In its evaluation of the CCC, the American Youth Commission commented that the Army's mode of operation produced an authoritarian atmosphere in which real exposure to democratic principles was impossible (see also Marsh, 1934).[88]

It is important to note, however, that even the front line professional camp educators hired by the CCC, realized that education and training in the camps should not mirror those of "progressive" public high schools. The enlistees were mostly wash outs from the public school system and wanted no part of the standard forms of schooling. By combining work and vocationally relevant study, the CCC hoped to (and did) reach this clientele (Sloper, 1940; Williams, 1940). Knight (1951), for instance, reports that in all the CCC aided more than 80,000 young Americans whom were totally illiterate when they entered the camps.

By 1937, the relief provision for new recruits had been removed. Although youths with parents on relief were given preference, young men from more financially secure families were now allowed to enroll. The initial CCC function as a welfare agency had become outmoded. It was now ready to concentrate more fully on its other official goals: (1) to function as a vocational training vehicle and entrée into the slowly recovering economy; (2) to make enrolled men into self-supporting and useful members of society; and (after 1939) to (3) prepare these youths for modern mechanized warfare (Oxely, 1940).[89]

The NYA (Its political and ideological mandate).

Part of this debate over education in CCC camps had to do with the ongoing turf war between the Roosevelt administration and the thoroughly conservative NEA.[90] New Dealers like Aubrey Williams (Director of the NYA), were convinced that few public school teachers would have the courage to teach the truth about the injustices of American society, that educators regarded many youths as uneducable, and that the public school system did not equip either lower-class youths or adults to cope with the massive dislocations of modern society (Williams, 1940; Judd, 1942; Salmond, 1983; Tyack, et al., 1984). In 1934, NEA officials began openly complaining in the pages of the NEA Journal and in Phi Delta Kappan that the New Deal was neglecting public schools.

Since the Roosevelt administration had rejected blanket "general" appropriation of federal aid to state in favor of the creation of relief agencies that would specifically assist the poor, it was accused of being class-conscious and (by implication) un-American (e.g., Givens, 1935). The New Dealers, however, viewed their own overall approach as reforming standard educational practice and rendering it class-neutral. In the interest of political expediency, however, a conspicuous role for certified teachers was drafted into the National Youth Administration program (aimed specifically at lower middle-class youth).[91]

The NYA was ostensively designed to: (1) provide part-time employment for needy secondary school, college, and university students aged 16 to 24; and (2) to provide work experience for high school graduates with families on relief. The NYA's employment of young people on school oriented work projects and university campuses (starting in January of 1936) relieved much of the political pressure that gave rise to the agency. The way had been cleared for such specific NYA job placements when the U.S. Commissioner of Education, George Zook, pronounced a successful conclusion to the experimental one-year FERA sponsored work-study program at 51 colleges and universities (during the 1934-35 term). Federal work relief would now help students continue their education and would offer fiscally embattled college presidents with a short-term labor force at no expense to themselves (see fig 40).

Figure 40 NYA student work placements. Guidelines for these student jobs allowed a maximum of twenty dollars per month during the academic year and stipulated that such jobs must be new (i.e., not previously budgeted for by the educational institution). They also mandated that the college and universities must select "eligible" students who carry three-fourths of the usual academic program and that the institutions must actively supervise the student work assignments (photos from Lindley & Lindley, 1938).

The continuance of the NYA program from 1936-1943, was partly due to the fact that its increasingly ideological content opened up possibilities to test the middle-class reception to the administration's wider re-alignment toward national security issues. On this foreign policy front, advocates of democratic ideological maintenance, both within the New Deal administration and from the wider community had made successive warnings that ideological radicalism in European youth was on the rise and that special programs for American youth should be brought into place.[92]

Youthful discontent was certainly nationwide by 1935 and fears were expressed within the New Deal administration that some Pied Piper, some domestic fuhrer, might soon produce undesirable changes in the American way of life (see Davis, 1936; Fass, 1977).[93] The burning question was now whether the New Deal ought to portray the NYA as an explicit democratic indoctrination alternative to the European totalitarian youth movements. That is, should it present itself as an ideological institution that was explicitly designed to justify the faith of young people in the fundamental richness of democratic institutions?

Resident NYA Camps (Ideological maintenance).

Roosevelt initially rejected various ideological management overtures made by both New Deal insiders (such as Robert Wagner; A. Williams; and Charles Taussig) and by pragmatic outsiders such as Owen Young (Chairman of the Board of General Electric).[94] In the face of these rejections, the initial NYA Deputy Director (Richard Brown) was bound to administer the NYA purely as a relief program for its first year (Loucheim, 1983). Even though the NYA would soon become an increasingly more ideological endeavor it would not do so explicitly. The program continued to be portrayed as a call to national service for the lower middle-class.

But, by June of 1936 the organizational tide had turned in favor of ideological maintenance initiatives when disturbing events accompanying the rise of German fascism -including the growing number of Jewish (or so-called non-Aryan) economic émigrés seeking placement in the United States. At this time, Aubrey Williams, as Executive Head of the NYA, was permitted to explore previous FERA sponsored "resident" summer camps for women as a possible prototype for future ideological NYA initiatives aimed at: (i) blue collar working women; (ii) rural youth; and; (iii) European refugees.[95] Thus, between 1937 and 1938, as FDR was attempting to move the political center leftward, the NYA's resident training centers began to dot the countryside (Dallek, 1979).

The resident camps for women, used as a prototype, were partially a continuation of the earlier FERA program of resident schools launched in 1934 by FERA and transferred to the NYA in 1935. However, there was a considerable shift of emphasis in the educational aspects of the camps away from the earlier emphasis on the FERA based "understanding" toward an emphasis on the NYA strategy of education for vocational and societal integration.[96] As Reiman (1992) points out, the FERA camp women required job skills, not a discussion of Sherwood Anderson's Puzzled America -a book used occasionally at the resident schools (p.149). Ironically the actual FERA women seemed particularly susceptible to the anomie which the NYA officials now hoped to avoid. On the positive side, however, the FERA women's program achieved in some camps what the CCC dared to permit in only the rarest cases: racial integration (see Sitkoff, 1978; Rose, 1994).

The second target group for resident camps, rural youth, were to be relocated to rural camps where group organization, fresh air, industrial education, and citizen training would be provided (Burns, 1989). By 1937 the NYA began setting up ambitious industrial projects and this development promised to be of particular usefulness to rural youth. This is because regional differences in the U.S. still meant that many rural youths (living in isolated communities) had nowhere near the exposure to modern industrial advances. These youth also had little opportunity to learn about what the structural underpinnings of American society might mean for their home communities and for their personal vocational future.

The emphasis of ideological maintenance for resident rural youth was on guiding youth into the realistic vocational pathways of industrial, not agrarian, America (Reiman, 1992). This would be accomplished through a combination of work placements and formal classes providing workshop experience in steam heating, plumbing, cabinet making, auto mechanics, sheet metal, welding, and commercial foods production. For example, NYA youth attending day-time work placements in automobile shops would attend classes on the theory of the internal combustion engine in the evening. Business English was offered, shop mathematics became standard fare at the newer centers during 1937 and 1938.[97] This substitute socialization program (involving work, education and citizenship training) was aimed at integrating the rural youth back into wider society.[98]

But by 1937, it was already too late for such an ambitious economically based resident plan to achieve fruition. The burgeoning hopes for a benevolent ideological maintenance emphasis of the resident programs were cut short by the actualities of overwhelming national defense needs. NYA planners, who initially considered the example of Hitler in 1934, now recognized that the ideological aspects of youth programs would not be aimed at forestalling the rise of a domestic dictator. They would, instead, be aimed at helping the country prepare American youth to face the present threat of Nazi expansion in Europe.

Part of the testing ground for this new national readiness mandate was then carried out through the inclusion of a small number of European refugees in the existing NYA resident camps.[99] Roosevelt had to reckon with a tide of "nativistic nationalism" an old, seldom dormant, and easily awakened American tradition (see chapters 2-4). In addition, the argument that refugees take jobs from "native-born" Americans was especially pointed during the "Roosevelt recession" of 1938 (Polenberg, 1966). Patriotic and veterans' organizations, for instance, were fiercely opposed to any efforts to admit more European refugees (Breitman & Kraut, 1987).[100]

When the Nazis embarked (in November 1938) on an active physical intimidation campaign against European Jewry (under the rubric Kristllnacht "night of broken glass"), domestic criticism of possible refugee assistance was only briefly muted. The administration's political balancing act between pro and con organizations necessitated the President's Advisory Committee on Political Refugees which resulted in the relaxing of visa requirements (by reducing the period for which private groups would be required to financially assist incoming refugees).

During this window of opportunity, the New Deal administration also moved to further break down isolationist resistance by transforming the public image of refugees from a faceless amorphous mass of aliens to a familiar group of individuals soon to become Americans. The main vehicle for accomplishing this objective was the placement of previously sponsored refugees into the NYA resident centers (Baumel, 1990).[101] As so often in politics, the needs of those to be rescued would await the cultivation of American public opinion. In this particular case, too, the results of the ideological mandate were doubly ironic. Most of the refugee youths who ended up in the rural camps were from big-city backgrounds and had far more education than the NYA youth with whom they lived and worked (Reiman, 1992).

Ending of the Youth Programs (War preparedness begins)

From 1939, onwards, the all-out conversion of the resident centers into training centers for national defense cost the NYA its initial emphasis on job training for the sake of the enrollees themselves. This was the year in which war between Germany and England was declared and a Western Front of German military expansion was successively widened. In April 1939, in a major government reorganization effort, FDR asked that the NYA be place in the Federal Security Agency (FSA) where it would receive appropriations directly from Congress (not the WPA). Between 1939 and 1943, the NYA camps participated first in the defense program and then in implementation of war production efforts. Average enrollment in the 595 operating centers in 1940 was 27,685, or about 10% of NYA youths nationwide.[102]

In 1941, the NEA sponsored "Educational Policies Commission" (EPC), issued a report on the CCC and NYA. These educators recommended that the two agencies be discontinued and their functions transferred back to the public school system. In their view, the "youth problem" (i.e., the gap between the average school attendance and the requirements of the workplace) could be solved when the federal government backs off and lets the schools extend their curricula to help all young people attain vocational competence. If sufficient support was now given to the public school system, there would be no out-of-work youth (EPC, 1941).

Judd (1942) counter-argued the EPC report by pointed out that the real youth problem did not lay in the lag time between youth learning and adult working but in the wider problematic disconnection between education, industry, government, and labor. In his view, instead of continuing the turf wars between federal government and National educational associations, what was needed, was a penetrating analysis of the American industrial system and of the relation of youth to this system (see also Judd, 1940). But this is precisely what (as a matter of disciplinary survival) the educational, ability testing, and industrial psychology communities had been consistently avoiding for two decades (see Wesley, 1957; Baritz, 1960; Gilb, 1966). The debate, as it turned out, was purely academic because real-world events intervened to settle things when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor (home port for much of the American Pacific Fleet). The official American entry into W.W.II called a halt to both the CCC and the NYA.

The New Deal had made a beginning in putting unemployed youth to work, but it reached only a fraction of those who where in need. The sudden demand for labor and troops in W.W.II seemed to end the "youth problem" by eliminating the considerable gap between school completion and work. It also deferred the "deeper" (more critical questions) that had been raised by educational radicals regarding the changing inter-relationship between youth and modern industrial culture and its effects on the nature of the development of human intellect (see Gilb, 1966). By July 1942, 24,074 of the residents were beginning training for war work representing 28.2 % and shortly thereafter, all NYA youths were streamed into the war effort due to the closing down of all non war youth training. In the spring of 1942 the Senate Committee on Education and Labor moved to terminate both CCC and NYA.

The CCC probably did as much to prepare the United States for participation in World War II as any other government agency. Ninety percent of the 3 million CCC enrollees later served in wartime. They were already accustomed to barracks life and they were disciplined (having learned not only how to take orders, but also how to give them). Approximately 50,000 Reserve Officers, for instance, had previously gained valuable experience in the CCC, leading and administering men at the Company level or at District Headquarters. These CCC educational and training initiatives were expanded by September 1940 with such national defense goals in mind.

The emphasis in the CCC, however, was placed on developing noncombatant skills that would be essential to the function of modern military organizations. In 1941, 266,759 enrollees completed units of such vocational instruction. That year, five-hundred enrollees at a time were attending twenty-six Radio Schools learning to become radio operators and technicians. Thousands of CCC-trained cooks and bakers later served in the mess halls of the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, as did the CCC-trained auto mechanics at military motor pools in the U.S. and overseas (Hill, 1990).

Section Two:

World War II Testing and Training: Psychometric ideology regained

This section highlights the various ways in which vocational and intellectual ability testing were utilized during World War II. By the time America officially joined the ongoing international war effort against the Axis Forces of right wing Nazi Germany and Italy (1939-1945), and against Imperial Japan (1942-45); the economy was already on a wartime upswing due to the Lend-Lease Bill (1941).

Long-lasting alliances were being forged between not only industry and applied psychology but also between the public education system and the older ability testing tradition. A fair but critical account of these emerging alliances is now possible given the cumulative historical record. This section provides a few touch stones for that analysis by mentioning the political/military context of war readiness; the preparation for war by mainstream psychology; and the eventual use of psychometrics in military induction, assessment, and training during W.W.II.

Political and Military Context of War Readiness

The initial tactical and technological trial grounds for World War II took place in Spain and China. Between 1936 and 1938, the Spanish Civil War (in which an elected leftist coalition government was overthrown by the right-wing dictator Franco) allowed Nazi forces to test storm trooper tactics and aerial bombardment of civilian populations (Fyrth, 1986; Aldgate, 1979). Similarly, what was later considered the first battle of W.W.II was fought between expansionist Japanese forces and defending Chinese Nationalist troops near Peking in 1937. The fanatical nature of Japanese incursion was revealed in Nanjing, where 300,000 Chinese civilians were callously slaughtered by Japanese foot soldiers over a six week period (Sun, 1993). The expansionist campaign was supported by a national consensus in Japan that viewed the material resources of the South East Asia as rightfully belonging to a consolidating empire from that region (rather than to foreign -France, British, or American- trading companies).[103]

In Europe, Nazi German forces had annexed Austria in March of 1938 ostensively at the "invitation" of the Austrian government (as a means of staving off trumped up Polish military incursions). German ground forces then marched into Poland on September 1, 1939 (Shachtman, 1982; Prazmowska, 1987). England and France declared war against German two days later. Now that the European "phony war" was behind them, the Nazi war machine launched an all out blitzkrieg ("Lightning war") toward the West capturing France and throwing back the Allied armies to the English Channel at Dunkirk (Perrett, 1983; Calder, 1991). An impromptu cross-channel rescue of Allied personnel from the Dunkirk beaches by a motley assortment of British water vessels ensued.[104]

In America, the earlier signing of both the so-called Hitler-Stalin Non-Aggression Pact (on August, 23, 1939); and the later "Tripartite Pact" (in September 1940) between Germany, Italy, and Japan, were successive blows to those who advocated further isolationist appeasement of European Fascism. The unexpected collapse of Allied forces in France brought with it the possibility that the British Navy might soon fall into the hands of the Nazis if extensive American intervention in the Atlantic region was not forthcoming. The predominant American military strategy to this point had assumed that Britain and France land forces would be sufficient to contain the expansion of Nazism in Western Europe (allowing the Americans to take a manageable offensive posture against expansionist Japan in the Pacific). The envisaged limited American aid in the Atlantic region was no longer tenable.[105]

The federal Lend-Lease Bill (of March, 1941) allowed the President to sell, transfer title to, exchange, lease, lend, or otherwise dispose of any defense article to any nation whose defense he deemed vital to U.S. security (Dobson, 1986). Extensive conveys of ships would now pass across the Atlantic to aid in the Allied defense of Britain. As American factories retooled for war, a total trade embargo against Japan was brought into place. This was done as a means of leverage for ongoing diplomatic negotiations regarding the immanent Japanese takeover of French Indo-China (later called Vietnam) and their military campaign in China.

The surprise Japanese attack on the Pearl Harbor (on the morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941) was intended to annihilate the preponderance of the U.S. Pacific Fleet in one swift blow. Although the Japanese attack failed to destroy the primary targets (the aircraft carriers Enterprise and Lexington), it did succeeded in prolonging the defensive posture of the American Pacific Fleet (Gailey, 1995). It was simply a matter of time, however, before American industry could produce enough additional naval power to assume an aggressive posture in both the Atlantic and Pacific theaters of war.

Pearl Harbor was a monument to the strengths and limitations of American preparedness in terms of military intelligence and warfare technology.[106] On the plus side, deteriorating political negotiations combined with overseas naval movement reports (by Naval Intelligence); and with domestic telephone and radio surveillance of the Japanese embassy in Washington (by the FBI), led the U.S. to expect an imminent attack on American forces in Indo-China with possible concurrent espionage activities in other locations. In accordance, an important precaution was taken at Pearl Harbor: the resident aircraft carriers were ordered to leave port along with half their Army aircraft (Parkinson, 1973). However, despite frequent allied air-patrols in the region, and despite use of new experimental radar (by Army Intelligence) the Japanese Strike Force (including all six carriers) had sailed unopposed into Pearl Harbor.[107]

Manning the American war machine (Vocational retraining)

The noticeable changes in industry during W.W.II paralleled those of W.W.I. Manpower shortages. These shortages led companies to emphasize the assessment for training of their available workers (Metz, 1942; Connery, 1951; Nash, 1989; Gillespie, 1991). Virtually every factory installed apprenticeship and upgrading programs and many of them utilized vocational tests (provided by the War Manpower Commission) to guide those training programs (Flynn, 1979). The interesting aspect of this testing was that it took place after the worker was hired. Thus, the vocational assessment tools were intended to function as one indicator of the most likely route of efficient training (or placement) within a company rather than as a means of employee selection per se. Such post hoc testing and counseling programs became the order of the day for war industry work (Tiffin, 1942; Super, 1942; Blum, 1976).[108]

Better work opportunities for Black Americans and women in general were also produced by wartime munitions contracts. Nearly a million housewives took jobs producing airplanes, tanks, large guns, cargo ships, or small arms ammunition for the war effort (Milward, 1977). Price controls and rationing ensured the cost of living did not increase after mid-1943. Better jobs and more overtime increased wages for women by roughly 70 percent (Litoff & Smith, 1996).

Just as in W.W.I, so-called "Negro" workers also poured into defense industry jobs. While their generally low vocational status reflected the inevitable results of past inequity of access to basic education, many Negro war workers were no worse educated than their White counterparts in better vocational positions. Despite the ongoing purely discriminatory practices of management and unions of the age (including differential placement and wage scales) Negro workers were at least able to obtain a sound foothold in both the industrial workplace and in segregated Army training programs. On the domestic front, Negroes became organized as a formidable political force through their "Double V" (victory abroad, victory at home) program, orchestrated by the Black press (Lichtenstein, 1982; Cook, 1964; Washburn, 1986).

Formerly wayward American youth, cast adrift by the depression era economic calamity, were also now provided with opportunities by entering into military service. In particular, volunteers for service could pick which branch of the service they preferred: Army Air Force, Navy, Marines, or Coast Guard. After Pearl Harbor there were floods of volunteers for the Army and Navy air corps. Women were also allowed to enlist for entry into noncombatant occupations.

Finally, the war draft itself called nearly 15 million American more or less reluctant American warriors into the armed forces. For these enlistees, basic boot camp was followed by advance training schools erected on college campuses (Davis, 1948; Stouffer, et al. 1949). For Naval Reservists, Army Militia, and college-trained R.O.T.C. officers, however, combat came much more quickly (Stuit, 1947). In due course, nearly 19 million Joes and Janes enlisted -11 million in the Army Infantry and Air Corps; 7 million in the Navy & Coast Guard; and nearly 700,000 in the Marine Corp.). They saw action and provided support in the Pacific, Europe, Asia, and North Africa theaters of war.

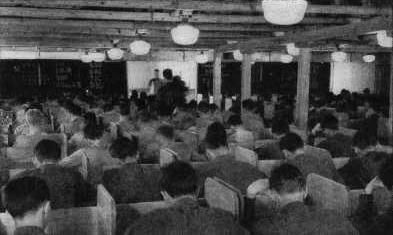

Psychologists Prepare For Another War

World War II brought academic and applied psychologists into direct contact with each other and with the war effort. The operation of increasingly complex weapons of war, such as high-speed aircraft, required specialized skills. The need to identify and classify recruits who already possessed the required skills (or who might readily learn those skills), led so-called military psychologist to apply and refine the psychometric techniques of test reliability and predictive validity. By Victory against Japan Day (V-J Day), more than 1,100 classification officers and interviewers (enlisted personnel) had been trained and assigned to provide classification services at more than one hundred Naval facilities ranging from stateside recruit training centers to forward area personnel distribution points. This was, therefore, an era in which the administrative ideology of psychometrics was reasserted (and somewhat vindicated) in a modern military-industrial context.

Depression era testing developments

The psychometric subdiscipline had survived the great depression era by: (1) further embracing the sociology of industrial management (including opinion polling of workers in factories and vocational guidance in schools or government settings); and by (2) refining statistical standards for test validity and reliability (including standardized educational or college entrance exams and cross-sectional or longitudinal research designs). As indicated below, both of these subdisciplinary coping mechanisms would be extremely advantageous in the W.W.II military setting (in which the primary concern was to select, classify, and train recruits as efficiently as possible).

During the early 1930s, the twin horrors of economic depression and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (C.I.O) rose up to haunt industrial management (Slocombe, 1937; Walsh, 1937; Pressey, et al., 1939; Zieger, 1995; Rosswurm, 1992). From a sociology of management perspective, these trends toward labor rights would have to be rendered vulnerable to attack by way of a fuller understanding of employee's thinking, attitudes, and social actions. Hence, industrial psychologists and personnel departments continued to play a role in the depression era restructuring of larger companies (Viteles, 1932; Keller, & Viteles, 1937). At the beginning of the depression, 31% of 302 companies surveyed had "industrial-relations departments" or at least directors, and more than half of companies employing over 5000 workers had such departments (Baritz, 1960, p. 119; Stevens, 1936).

The ongoing growth of union membership meant that seniority, not necessarily skill, would take precedence in rehiring workers who had been laid off (Galenson, 1960). For management, this simply meant that greater care would have to be taken in the original selection of incoming workers (Miller & Form, 1951; Scott, 1954). While several of the larger industries were already being organized by unions (with sit-down strikes, walkouts, and intimidation being used) employers not yet approached by organized labor were active in searching for dispositionally peaceful employees.

Similarly, attitude research and training programs might become useful in forestalling the leftward movement of existing personnel of a large company (Hoppock, 1935, 1938; Achilles, 1932; Kornhauser, 1946).[109]

The related, more subdisciplinary centered, emphasis on statistical standards was ostensively designed to increase the reliability of test results by either: (1) decreasing the error of measurement (e.g., multiple-choice vs. older essay test forms); (2) factoring out the effects of prior learning (in so-called aptitude tests); or conversely (3) by specifically assessing the long-term effects of training on test performance (in so-called achievement tests). Various articles and book length treatments came out during this period dealing with how these issues applications in both the psychology and educational subdisciplines (see Lincoln & Workman, 1935; Guilford, 1936; Hawke et al., 1936; Hunt, 1936; Wrightstone, 1936; Anastasi, 1937).

Of particular note, however, was the work of Oscar K. Buros who (in 1935) began an ongoing independent compendium of mental tests called the Mental Measurements Yearbook which, by 1940, had grown into its modern form. Commissioned reviews of recent tests were provided and each test was only reviewed again after substantial empirical changes had been made. Buro's original hope that the periodic M.M.Y. volumes would help foster ongoing improvements in the statistical reliability and validity of testing practices has been hampered over the years in various ways (Jensen, 1980; Mitchell, 1984; Snyderman, & Rothman, 1988; E. Hunt, 1995a).

Similarly, since all of the contemporary cross-sectional and longitudinal studies adhered to the invalid additive conception of human intellect (as nature plus nurture), psychologists were left with an administratively useful but ontologically vacuous scientific methodology (upon which both their increasingly reliable measurements and their theoretical conclusions depended). The very resurgence of the nature-nurture debate in the early 1940s indicates that the underlying methodological hypothesis of latent intelligence was alive and well in the immediate pre-war period.[110] Such a psychology of intellect could not lead to a deep understanding or a resolution of issues which faced teachers and New Deal government officials on a daily basis (i.e., class and racial inequalities of housing, schooling, and employment). Nor did it have any supportable scientific answer for those who openly adhered to racist doctrines. The latter failing, in particular, is partially due to the fact that their own founding additive assumptions were part and partial to ongoing eugenic and euthenics programs.

Having routinely bracketed (i.e., pushed aside) older debates regarding the production of qualitatively higher (i.e., literate human intellect) from lower forms of human and animal intellect, even well-intentioned social scientists were now left with little that resembled an effective argument against ongoing domestic state sterilization programs or against the growing efforts of Nazi (and Axis power) efforts to rid Europe of "the Jewish race." Nor did American psychologists have a viable argument against domestic right-wing fringe groups such as the German-American Bund party and the K.K.K. (see Howitt, & Owusu-Bempah, 1994; Smith; 1985; Guthrie, 1996).

Two conservative trends in psychometrics (i.e., ontological agnosticism in ability testing and the managerial orientation of industrial psychology), however, did not go entirely unnoticed or unopposed. In 1938 the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI), an affiliate of the APA founded in 1936, issued a Statement on Racial Psychology explicitly denouncing the continued use of fictitious Aryan racial category (see Morris, 1984) and the continued reliance on the spurious latent intelligence hypothesis:

"The current emphasis upon 'racial differences' in Germany and Italy, and the indication that such an emphasis may be on the increase in the United States and elsewhere, make it important to know what psychologists and other social scientist have to say in this connection....[The] emphasis on the existence of an 'Aryan race' has no scientific basis, since the word 'Aryan' refers to a family of language and not at all to race or to physical appearance. There is no evidence for the existence of an inborn Jewish or German or Italian mentality. Furthermore, there is no indication that the members of any group are rendered incapable by their biological heredity of completely acquiring the culture of the community in which they live. This is true not only of the Jews in Germany, but also of groups that actually are physically different from one another. The Nazi theory that people must be related by blood in order to participate in the same cultural or intellectual heritage has absolutely no support from scientific findings" (SPSSI, 1938, In Guthrie, 1976, p. 200).

Signatures to the letter included: Floyd Allport, Syracuse University; Gordon Allport, Harvard University; Franklin Fearing, University of California at Los Angeles; George W. Hartmann and Gardner Murphy, Columbia University; David Krech [I. Krechevsky], University of Colorado; T.C. Schneirla, New York University; and Edward C. Tolman, University of California. But such appeals to social ethics were, of course, only as effective as the practical alternatives which backed them up (Kuhl, 1994). These were sadly lacking in contemporary SPSSI arguments. For example, in 1940 the old debate regarding the relative importance of inheritance for human intellect was rekindled in to a formal debate between representative of Iowa under Stoddard and of the University of California under McNemar (Minton, 1984).

Another SPSSI critique aimed this time against the conservative management bias of testing programs was presented in the first SPSSI yearbook (Edited by George Hartmann and Theodore Newcomb), Industrial Conflict: A psychological interpretation (1940). This was put out from an explicitly pro-labor standpoint (Baritz, 1960; Finison, 1979). Several of the contributors pointed out that the dominant conservative climate had seriously infected the social science discipline. This, and successive SPSSI sponsored volumes, would help broaden the perspective of experimentally oriented "social" psychologists during the war -by discussing the causes of industrial conflict or of war, and by actively wrestling with the issues of civilian morale during war and or securing an enduring peace (see G. Watson, 1942; Tolman, 1942; Murphy, 1945). It is also clear, however, that such volumes lacked an explicit systematic methodology by which to differentiate the practical/empirical implications of their own position from that of others. In addition, as indicated in chapter 6, there were both military and political forces building in America that would systematically rid left-leaning solutions from the expanding system of post-war higher education.

Many of the contemporary applied psychometricists and psychologists, had already fully embraced the conservative "data oriented" trends of ontological agnosticism and empirical operationism. They remained entirely unswayed by (or simply ignorant of) unpopular collectivist arguments from the political left. The two rightist trends (of statistical methodolatry and management bias) must therefore be recognized as the dominant trends in the pre and post-war industrial psychology. These trends were reflected directly in other events including: the founding of the Psychometric Society (1935); Guilford's (1936) Psychometric Methods (which outlined his method of Factor Analysis); and also in 1936 the first Invitational Conference on Testing Problems and launch of Psychometrika.[111]

Emergency W.W.II Committees

The 1939 APA meeting was in session when Hitler began his invasion of Poland. A joint emergency committee was then established between APA and AAAP with Walter R. Miles as Chairman (Miles, 1940).[112] A Conference on Morale was subsequently held in Washington on November 2-3, 1940 (Dallenbach, 1946). Similarly, an Emergency Committee appointed Subcommittee on Survey and Planning, (under the chairmanship of Yerkes) met from June 14-20, 1942 at the Vineland Training School.

The Subcommittee was made up of members evenly divided between experimental and applied interests including: Yerkes, E.G. Boring, A.I. Bryan, E. Doll, R. Elliott, E. Hilgard, C. Rogers, and C. Stone. The ongoing disciplinary cooperation between clinical, applied, experimental, and psychometric psychologists, then extended outward to include collaboration between the Psychological Corporation, the Psychometric Corporation (founded 1935), and the College Examination Board in establishing the grounds for a psychological contribution to the ensuing war effort (see Boring et al., 1942; Hilgard, 1945ab; Wolfe, 1946). The overall result was that when Japan finally did attack Pearl Harbor, the American testing community was much more prepared than it had been in 1917 to assist in the selection, classification, and training of newly enlisted personnel. By this time, for instance, various versions of the Army General Classification Test (AGCT) had already began their use.

Military Induction (Procedure and Testing)

With the passage of the Selective Service Act (in the spring of 1940), a Personnel Testing Section was established under the War Plans and Training Officer of the Adjutant General's Office. The Army officials in charge of personnel selection and classification (including Yerkes and Bingham of W.W.I fame) tried to place the entire induction program onto a "merit" foundation (Thomson, 1943; Capshew, 1986). The new recruit, upon induction was given various physical and mental examinations.

In this overall cooperation between medical practitioners, mental testers and applied psychologists, the term "selection" was typically used to describe measures designed to determine qualification for service. The term "classification" was used to indicate potential for success in billet assignments or "Specialized Training" programs (ameliorative or advanced). When a test battery was designed to perform all three functions, however, it was simply called a "qualifying" exam (Stuit, 1947; Davis, 1948; Stouffer, et al. 1949).

Physical Examinations